Nicholas Harding: Australian painting’s great loss

Some of Nicholas Harding’s final landscapes before his death reflect our brief presence in the endless flow of being.

Nicholas Harding’s premature death at the age of 66 is a great loss, not only to his bereaved family and his affectionate friends, but to Australian painting. He was a gifted artist who demonstrated the scope of the art of painting at a time when many undervalue it or are content with debased forms of the practice. And he was exemplary in possessing two qualities that are relatively rare today: aesthetic integrity and a capacity for growth and development.

His integrity, as a man and as an artist, was innate and evident in his process of self-discovery as a painter. He had a natural talent for drawing, which soon gained him employment as an animator, but had not been to art school and had to find his own way to higher ambitions. Perhaps in the end this was an advantage, for the late 1970s and the 80s were far from a golden age for painting or painting instruction.

Today, the situation for an aspiring painter is, if anything, even worse. Art schools regularly discourage attempts at authentic practice and almost all institutions value fashionable gestures and ideological posturing above talent, skill and vision. In recent years fraudulent practices, like painting over printed photographs, have crept into prize exhibitions, both of portraits and landscapes, and incompetent judges have even fallen for these deceptions.

For a true painter like Harding such dishonesty is unimaginable. The passion that drives a painter to struggle again and again to render an account of the world that is meaningful, expressive and harmonious is incompatible with such cynicism. Like all good painters, Harding forged, each time anew, an artificial visual world of colours and tone animated by the surge of inner imaginative vitality.

The capacity for artistic development is also surprisingly rare. Too many painters in Australia show early promise but are incapable of improvement. If they find one winning formula, they stick to it and repeat it; art schools aggravate this tendency because they encourage students to settle on a distinctive look or brand as soon as possible, while failing to equip them with a broader training that might permit them to grow and change in an organic manner.

I had known Nicholas and his work since the later 1990s – and indeed our children were at the same school at the time – and seen his exhibitions at Rex Irwin’s gallery, but I first reviewed his work properly on the occasion of his retrospective, Drawn to Paint, at the S.H. Ervin Gallery in January 2010. One of the things that I discussed then was the nature of the development that had taken him from the dark cityscapes of his early work to what was then his relatively recent turn towards landscapes and an entirely different colour palette.

Harding’s early style was influenced by English modernists from Walter Sickert to Auerbach and Freud, and especially Leon Kossoff, whose own 2007 retrospective at the National Gallery in London had been subtitled Drawing from Painting. But I suggested that these artists, with their emphasis on the weight and materiality of paint itself, belonged to a fundamentally different culture from the optical tradition initiated in the Renaissance. Instead, they were concerned with coaxing the inert substance of oil and pigment into life.

Harding’s early paintings were, like his British models, painted in thick impasto, the pigments worked and reworked into almost monochrome darkness. This is the opposite of the effect Seurat sought with his theory of divisionism: whereas the optical mixture of pure colours ultimately results in white, as suggested by the little girl in a white dress in the middle of La Grande Jatte (1886), the mixture of pigments is subtractive and every degree of mixing leads to a gradual loss of both light and chroma.

This style was well suited to the subjects of the early paintings, which were generally urban landscapes or interiors, executed in a sober and even drab palette dominated by greys, browns and greens. The drawings of this period represent a graphic analog of the same style: Harding worked on heavy art paper, but the process of drawing, erasure and redrawing in the search for formal resolution was so obsessive and ferocious that the surface of the paper was lacerated and sometimes even worn through.

Early in the new century, and after giving up his earlier career in animation, Harding’s style evolved from stiff impasto towards greater freedom and fluidity of handling, and at the same time the dark palette was replaced with a much brighter one, with fresh colours and a new pleasure in natural light. As I pointed out at the time, however, this new style was less well suited to urban subjects and architectural motifs, which sometimes tended to appear too literal.

On the other hand, a more agile and responsive style proved ideally adapted to the subjects of nature, plants and landscape that increasingly appealed to Harding during these years. At first these landscapes were populated by figures, and there were interesting differences between seascapes and the riverscapes and the ways that figures were used in each.

Meanwhile Harding had also established himself as a fine portraitist. He first became more widely known to a general public when he won the Archibald Prize in 2001 with a portrait of John Bell in the role of King Lear, and he was for many years a regular finalist whose work always stood out among so many pictures of notoriously indifferent quality. Other well-known sitters included Margaret Olley and his friend Hugo Weaving.

In March 2014, I invited Nicholas to conduct two afternoon workshops on portraiture at Sydney Grammar School, one drawing and the other painting, and I ended up sitting as a model for these sessions myself. It was fascinating to watch the attention and confidence with which he approached the process, and the rapidity with which he captured the essential and characteristic features of his sitter.

In 2017, Harding’s work as a portrait painter was recognised in an exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery, Nicholas Harding: 28 Portraits. I reviewed this exhibition in October 2017 and was again struck by the paramount importance of drawing in his process. Like all portrait painters, he could use photographs as a reference in making a portrait, but he was able to do this without becoming a slave to the poverty of the photographic source because he had already drawn the subject and had understood, from this direct encounter, the structures and characteristic movements of their features.

This exhibition also included sketches done under the most difficult possible conditions, watching actors in rehearsal or in performance on the stage, rapidly capturing features and expressions. It was thanks to his friendship with Hugo Weaving that Nicholas was able to make these drawings in which his graphic skill and fluency were tested to the limits. They later became an exhibition and a selection was published as a limited-edition volume, From the Wings (2020).

It was just after my review of his exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery that Nicholas wrote and told me about his cancer diagnosis. He underwent gruelling treatment and seemed to make a good recovery; in the Archibald Exhibition of 2018 he showed a monochrome self-portrait on his last day of treatment.

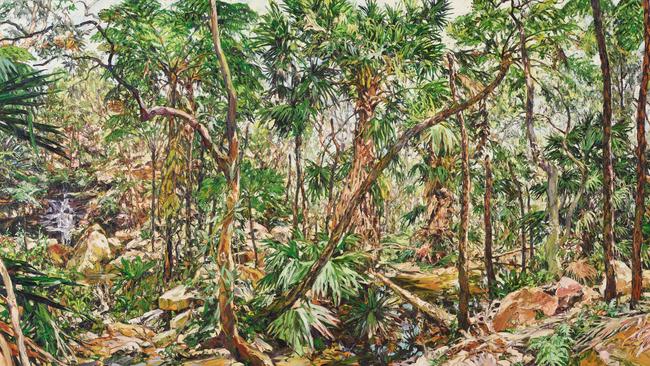

The last time I wrote about his work in this column was in August 2020, when after the end of the first Covid lockdown, Olsen Gallery was able to mount a beautiful exhibition of his new landscapes. These views of dense bush had relinquished many of the structural principles of classical landscape, and it was clearly only the same decisive graphic sense that underpinned his portraits that allowed Harding to keep compositional control of the increasingly complex and proliferating natural exuberance of these scenes.

Earlier this year, Nicholas Harding won the Wynne landscape prize but was already looking frail and ill, and he passed away at home on November 2. He is survived by Lynne, his wife of 48 years, and his son Sam. His final exhibition, as it turns out, opened less than two weeks later at Philip Bacon’s gallery in Brisbane.

For reasons of timing, travel and publication deadlines, I was not able to see the exhibition before writing this piece, but it is clear that it includes some remarkable works, including Ikara Wangarra (2022), which has been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia.

This appears to be the first painting of his that the NGA has acquired, not entirely surprising given their poor track record in supporting serious painters. Fortunately the print collection seems to own most of his print works.

This picture is an excellent example of Harding’s late landscapes that express an almost ecstatic absorption in the vibrancy and profusion of natural life; we are plunged into the bush, into a boundless world with no horizon, no edges, no sky. In anyone else’s hands, this could have been a scene of confusion; it is only because of Harding’s powerful graphic treatment of the two central trees, and the closer of the two in particular, that the whole composition can be anchored without losing the sense of irresistible electric energy.

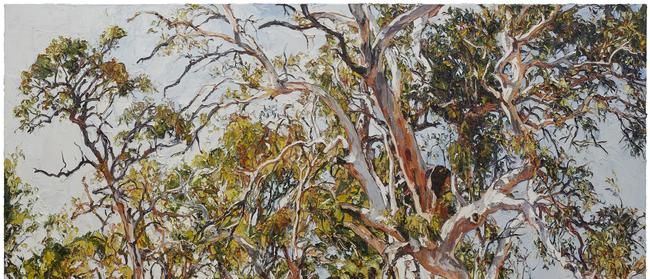

Another large and imposing landscape, Brachina Riverbed Grove (2022) is impressive in a different way. The trees in this picture are actually more complex, because they are the main motifs as well as the structuring principles of the composition. They are painted with an unparalleled expressive verve, like a powerful affirmation of life which is striking in itself but even more moving when we consider how unwell he already was.

At the same time, this painting, in which we rediscover a sky and a horizon and in which the trees are an unmistakeable homage to Hans Heysen, also suggests a new dialogue with the history of the landscape genre and indeed with the history of landscape painting in Australia. Harding’s development, which had already taken him such a long way, clearly had further to go; his death has interrupted a story that would otherwise have continued to unfold over the next couple of decades.

In contrast to these monumental and exuberant landscapes, there is one set of works in this exhibition that hints poignantly at the fragility and transience of life: a series of dragonflies hovering above water or perched on twigs. Tiny, ephemeral creatures, darting and then still and then gone, they are like allegories of our brief presence in and connection with the endless flow of being. The water below them is now light, now dark, reflecting the colours of the ever-changing day; the insects are poised in the alertness of attention. Perhaps Nicholas even thought of Yeats’s famous poem, which ends with the evocation of Michelangelo at work:

Like a long-legged fly upon the stream

His mind moves upon silence.

Nicholas Harding

Philip Bacon Gallery, Brisbane, until December 10

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout