Isolation, illness and ignominy: Annemieke Mein defies it all to become Australia’s eminent textile artist

Her parents suicided before her most significant exhibition opened. Then she lost feeling in her hands and feet. Is Annemieke Mein’s art imitating life?

Artist Annemieke Mein watches intently as a redback spider slowly uncurls her long front legs and feels her way around a clear plastic container. “Isn’t she beautiful,” she enthuses of the arachnid, which has been resident on her kitchen bench for the past few months, at home alongside the season’s harvest of zucchinis.

Every few days Annemieke keeps her muse happy with a Portuguese Millipede or the crunchy corpse of a cockroach, or perhaps some bark or leaves collected from the garden. And then she sits, and observes, and sketches.

“I found her in the veggie garden under a brick – her colour caught my eye,” she says. “I keep her under a wafer of cardboard because she likes the dark.”

Upstairs, the walls of the attic studio in Annemieke’s home in Sale, two and a half hours east of Melbourne, are lined with drawings of the delicate spider, the star of her next major work. Under the watchful eye of a bat cadaver and an imposing stuffed eagle, the spider sketches take pride of place among an eclectic collection of snake skins, seahorses, case moths in cocoons, wings of wasps and all sorts of other critters, waiting for the artist’s attention.

When she has captured the spider from every conceivable angle, both on paper and in her photographic mind, Annemieke will bring the vivid spinner to life as a textile work stitched onto canvas – this is her distinctive modus operandi as an artist – and at some point Redback Spider will join a collection of her work at the Gippsland Art Gallery. The well-fed muse will then return to the veggie garden.

“I’ve lived with her every day, I’ve watched her, drawn her and observed how she moves. She’s a little way off yet but I’ll get to the point where I know I’m ready to start work on her.”

At 79, Annemieke Mein OAM is having a career renaissance. Her ability to show the most insignificant and unloved of creatures (those we’re more inclined to take to with a can of Mortein) in a different light is drawing record crowds to the Gippsland Art Gallery where she has a permanent, rotating exhibition.

Next year, to mark her milestone birthday, the gallery will host a major retrospective of her life’s work, showing 200 pieces that have shaped her career and new works created for the occasion, offering long overdue recognition for her pioneering ecological art.

“Annemieke is arguably Australia’s greatest textile artist but she’s never been on the radar of the Australian art world,” says Simon Gregg, Director of the Gippsland Art Gallery in Sale.

“She’s a local rockstar, a major drawcard, she’s our (state’s) Margaret Olley. She’s been an outsider for the past 50 years, but her exhibitions here at the gallery have consistently drawn more interest from the general public than any other wildlife artist you could name. People queue up around the block to see her work. There’s no one else like her.”

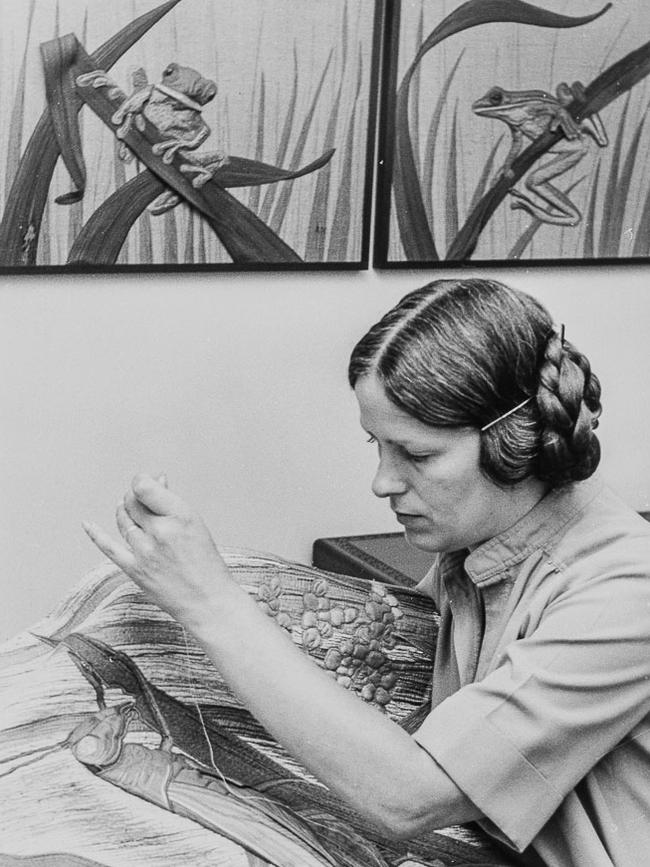

Annemieke conducts an unruly orchestra, corralling textiles she’s picked up on her travels to create the larger-than-life works that are made using up to 1000 pieces of fabric, painstakingly hand-dyed then stitched into place on the canvas. Her works can take a year to finish and the art is in the extraordinary detail – the inside of a bird’s beak, glistening fish scales, the shimmering body of a silverfish insect, all masterfully sculpted from silken thread or snippets of leftover wool or felt, a sliver of gabardine from her husband’s old coat or the remnants of a perfect red evening dress she found in an op-shop. Even the labels cut off an old mattress find a place.

She brings it all together in a majestic crescendo of native Australian flora and fauna that leaps off each expansive canvas.

With her Dutch braids curled Leia-like around her ears, Annemieke slides a cup of dried food through the kitchen window for the magpies tapping for their breakfast. The birds haven’t made it to one of her works yet – “too black and white”, she laughs as she flicks through a catalogue to find Coastal Banksia, the piece that launched her international art career in 1978 after working as a nurse. “When my kids were at kindergarten, I decided I wanted to go back to nursing,” she explains. “There was a vacancy at the local hospital in Sale but the matron said I couldn’t have the job because she wouldn’t have doctors’ wives working in the hospital – my husband Phillip was the local GP. I was terribly disappointed but Phillip said, ‘Well, you’ve always loved art and craft, this is your chance, why don’t you have a serious go at it?’” “Annemieke loved to create and her creations were exquisite,” Phillip says. “Hand-made cards, cross-stitch embroidery, sketching, painting, découpage, leatherwork, macramé, pottery, dressmaking. Everything. For a wedding present, she painted me a bullfighter which I still have and treasure.”

She took a stem of coastal banksia from her front garden and studied it, sketched it and made patterns for every skerrick of fabric needed to bring the banksia to life on canvas. The piece took three months to make and she was pleased enough with the result that she entered it in a competition run by Family Circle magazine. She won and soon found herself in New York as the special guest at a major textile craft fair.

-

“This was life-changing for me,” she says. “It was very powerful and so encouraging.”

-

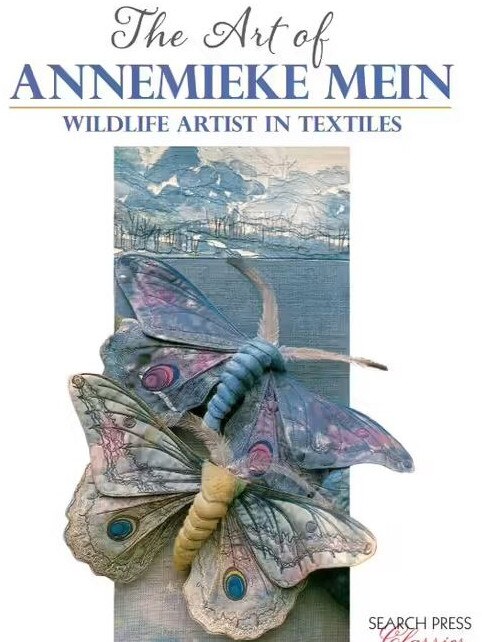

A year later Annemieke held her first exhibition at the local gallery in Sale, and within two years her works were purchased by the National Gallery of Victoria. Since then her pieces have toured Australia, New Zealand, Japan and the UK, she’s been presented to the king of Sweden and the queen of the Netherlands, and her book The Art of Annemieke Mein: Wildlife Artist in Textiles is estimated to have sold half a million copies, especially across textile-loving North America where it has been consistently in print since 1992.

It hasn’t been an easy path to success; in the early years some galleries snobbishly shunned her work, deeming it “craft” rather than art. In 1992, one prominent Melbourne gallery held an exhibition of her work despite the director protesting it would be a waste of time. “He had to eat his words,” says Simon Gregg. “We estimate that close to 100,000 people came to see her work.” He adds: “Crafts have tended to be denigrated in the hierarchy of fine arts but labels have never bothered Annemieke, she blurs the lines of craft and art. It’s been suggested there are feminist and environmental themes in her work. There’s a strong sculptural element, they are conceptually very refined and she has an extraordinary vision that she is able to realise through textile which makes her work so compelling; it transforms people’s ideas of what textiles can be. I don’t think anyone has done what she has in textiles or shown Australian native life this way.”

Incredibly, after the early success, her career came to a heartbreaking halt when she lost the sense of touch and feeling in her hands and feet. After years of searching for answers as to why, she was diagnosed with a rare neurological disease. She thought she’d never work again.

She is in no doubt that the onset of her illness was triggered by the shock death of her parents, who committed suicide in June 1996, cruelly as their only child was opening her most significant exhibition, The Fabric of Nature, the headline event celebrating the 150th birthday of Melbourne’s Royal Botanic Gardens.

Her mother died first, just after the exhibition opened, and her father three weeks later just before the exhibition closed. “We packed up Annemieke’s work into the car and drove home via the coroner’s office to identify her father’s body. It was horrific,” Phillip says.

“I didn’t want to work anymore,” Annemieke recalls. “I was shaking and couldn’t do things the way I wanted to. I thought I’d better quit while I was on top – I didn’t want my work to diminish.”

Annemieke Mein was seven years old when she arrived in Australia in 1951 with two people she didn’t know. Born in Haarlem in the Netherlands in 1944, her parents were heavily involved in the wartime resistance and underground movement, and incapable of looking after a child, so she was raised by her maternal grandparents whose influence was profound.

“My parents rejected me,” she says. “They came to visit every now and then but I was really raised by my grandparents, who were wonderful people. I have fond memories of my grandmother [Oma] stitching and sewing. Every day, morning, noon and night, she was doing something with fabric. By the time I was three years old I could sew.

“I would play with Oma’s button collection; she’d tip some of them out and get me to sort them by colour, and once we had all of the colours grouped we would divide them again and she’d say, ‘OK, which one is the brightest, which one is darker?’

She made me think very hard about the colours and patterns and grading shades and tone, it became intrinsic to me,” she says, pointing to the hundreds of little jars lined up in her studio, with bibs and bobs painstakingly sorted by tone and texture. It was a relatively happy childhood until her parents decided to emigrate to Australia and Annemieke’s elderly grandparents insisted they take their daughter with them.

While Annemieke fell in love with Australia’s natural environment, the human environment was an unwelcoming contradiction. Her parents worked long hours to get ahead and she was often home alone. She was made to cook and clean for them, and school offered no respite. She was labelled a “Hun” (a German) because of her accent, blonde hair and olive skin.

Annemieke’s father Lambertus, or Bert as he was known in Australia, was a temperamental and violent man who regularly beat her. Phillip later diagnosed him with delusional disorder, and her mother Johanna (Joan) with folie à deux – shared delusional disorder.

“I still have a scar on my arm from bruising,” Annemieke says, “and if I meet someone suddenly in a doorway or get startled, I get goosebumps and terribly frightened. I don’t do well with strange people.

“I can’t remember ever being hugged or kissed by my parents, I can only remember being belted from the time I was a young child. Suffice to say I over-compensated with love for my own children, Peter and Joanne, and my grandchildren, who I absolutely adore,” she says.

The only place young Annemieke found solace was in a towering gum tree in the backyard of their home in Melbourne’s Brighton, where she would spend hours studying the tree and its residents, collecting its insects, storing them in tiny matchboxes overnight and releasing them in the morning. Counting the life on the gum tree became a game, and an escape from what was happening inside the house. Unwittingly, it shaped her life. “I just loved that gum tree and the little bushes that surrounded it and the birds – they were my friends, and it had a great influence on my love of the natural world.”

In high school, Annemieke was still very much alone but her art teacher at Nunawading High, Mrs Ridgeway, took the vulnerable bird under her wing and helped her to fly. She invited Annemieke into the art room at lunchtimes and encouraged her to draw. Annemieke wasn’t allowed to draw or do art at home – her father would rip up her work – so she hid her drawings in her maths book and kept it at school.

“Mrs Ridgeway was a beautiful woman. I owe her everything. She encouraged me to become an art teacher so I enrolled at Melbourne State College, but it didn’t quite go to plan. For our first-term exam we had to draw a still life. The model was stark naked with rough skin and warts, and hair growing around her nipples. She was quite a picture and I’d never seen anything like that before,” Annemieke says, laughing.

“I drew her as I saw her and focused on some of the detail, like the chip on her tooth, and the warts on her face, but when I got my results, I’d failed! My friend drew the woman in a sweeping Picasso style and she got a distinction, and I thought, ‘That’s it, I’m out of here’. It seemed terribly unfair.”

Call it a twist of fate or a lucky break, but her doctor – who was aware of her father’s violence – called a friend in nursing who offered Annemieke a place at Royal Melbourne Hospital, where she could life in residence. She moved out of her parents’ realm that very day and never went back.

Nursing suited her gentle, caring demeanour, and finally she found the friends and freedom she craved. It was there that she met Phillip, who was a junior doctor. They married the same year and eventually moved to Sale where he was based as a GP.

The passionate ecologist and artist fell in love with the Gippsland region’s rich natural landscape – its rivers, wetlands, beaches and forests that are the heart of her work. “I’m very inspired by nature, and everything I create is from around here. Sometimes I’ll be out in the garden and see a little beetle and think, ‘You’re gorgeous, I’ve got just the right fabrics to make you…’ and off I go.”

Shortly after her parents’ deaths Annemieke developed a stinging sensation in her legs. It felt like she was “walking in boiling water on broken glass”, she recalls. It soon spread to her hands and she was forced to give up her art.

She went to doctor after doctor seeking answers about what was happening to her, and eventually was diagnosed with cryptogenic sensory neuropathy and trigeminal neuralgia.

For eight years she was unable to work, and spent much of her time trying to find a cure.

Realising she needed help to cope with these painful conditions, Phillip took her to Melbourne to see a psychologist who suggested she throw herself into something she was passionate about, such as gardening, to take her mind off things. She was sceptical, but on the drive back to Sale they came across a terrible car accident that turned her life around.

“It happened right in front of us, and Phillip being a doctor and me a former nurse, we jumped out of the car and ran to help these poor people. It felt like forever before the ambulance arrived and I was helping a lady who had quite bad lacerations across her face.

“I finally went back and sat in the car to catch my breath and noticed I had no pain. None at all. When I started thinking about it, the pain came back. The whole time I’d been helping this poor lady I hadn’t felt a thing. It was a real eye-opener for me: my mind could control my pain.”

That car accident effectively ended more than a decade of artistic exile.

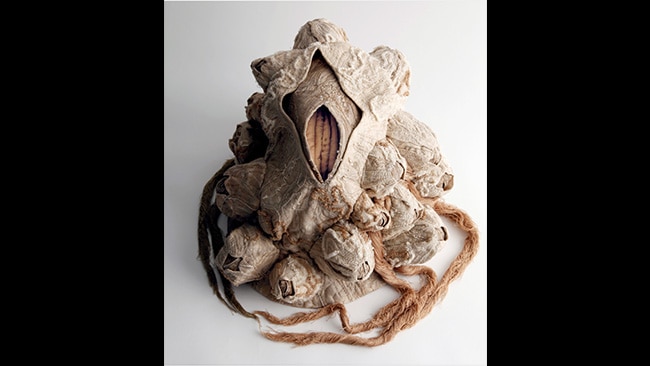

“I’d been cleaning out my studio thinking I was going to give things away and I came across boxes of clothing labels I’d saved since I was a little girl,” she recalls. “I just loved the silk fabric and these meant something to me. I had to make something with them. My fingers weren’t working properly because I hadn’t been working for years, so I devised a way around it with iron-on fabric, and I made this whole work out of clothing labels.”

It took seven months to complete the striking piece La Bel (a play on the word label), which was a key exhibit at the opening of the new Gippsland Art Gallery in 2018. She says the deeply personal piece of work kickstarted her career again.

“It was so popular, people asked me to make more work from the labels but I didn’t have any more. Now they arrive from all over Australia,” she says, pointing to a pile of letters on her desk.

“I’m thinking my redback might be made out of labels… we’ll see.”

Although Annemieke can no longer feel the delicate silk thread or fabric she uses to create her creations, she has adjusted and found new ways to continue working. She can hold a pencil and draw and do just about everything she used to do, albeit her fine sense of touch is gone.

“My eyes tell me everything now,” she says. “I don’t have that lovely sense I once had – I could feel a piece of material and know if it was silk or wool or hairy or bristly. I can’t tell that at all anymore. I miss the feel of Phillip’s skin.

“It took a lot of courage to keep going and create again. I didn’t think I could still do the work, and to be honest I’m astonished I can and I’m loving it more than ever.”

Along with her prized redback spider, she’s been “wrestling” with a Botany Bay Weevil, which will feature in next year’s exhibition as a 3D sculpture.

“I’ve got specimens from my garden,” she says. “Phillip thinks they’re pests – their long snouts stick into plants to suck out their juices – but they’re so beautiful, just gorgeous… I hope my work helps people appreciate our beautiful wildlife. My work always carries an environmental message.

-

It says, ‘Look at me, I’m beautiful, I’m worth preserving’.

-

Simon Gregg hopes that after six decades of creating, Annemieke Mein will at long last be truly recognised for her art.

“This exhibition is intended as a big thank-you from us to her, and an opportunity to celebrate what she has given to the gallery and the wider community,” he says.

“She’s a living treasure. The combination of what happened to her parents, her subsequent health and a bit of snobbishness in the art world when she wasn’t recognised as a legitimate artist, meant we lost her for a time – but she’s back, better than ever.”

Tickets for the exhibition, opening on March 2, go on sale soon: gippslandartgallery.com

Lifeline 13 11 14; beyondblue.org.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout