I thought I might never write again - thanks to you I found the words

I’d lost my confidence. The elixir of self-belief had vanished. You, dear reader, helped me get it back.

I’m in a high school. An auditorium of girls and boys. Watching a music concert, as a family friend. Solo pieces. Such concerts are routine at this school where performing is the specialty. I’m sitting down the front so can’t easily see what’s happening behind me. But I can hear it. The tribal roar, whenever one of the boys finishes his turn, from the other boys.

A deep, sustained, declamatory bellowing that goes far beyond supportive applause for their peers; testosterone-soaked and primal, dominating and exhilarating, and which – this is important – seems to have little to do with the musician’s expertise. It’s about something else. Connection, uplift, veneration; a ring-fencing. These are young men signalling to other males, for everyone to hear. This is us.

I feel a sharp little pain, for those valiant female performers, in that moment. For this roar of approval and affirmation is never quite afforded them, no matter how accomplished. The starkly muted response to the girls is as performative as the over-the-top bellowing for the boys. It feels like a ghosting, a lessening; a shard into fragile, hormonal self-belief. Those boys are making a point. It is the arc of repetitious history as all these teens soar into their futures, watched by adults who have their hearts in their mouths over whether they will fly, must, please; yet this roar, in this moment, feels like a history that only falteringly changes for females. Two steps forward, one step back, and the viciousness of the pushback.

Crueller, louder, angrier. Territorial. As if the sound in the auditorium encapsulates all the confusion and hurt playing out in the battle of the sexes in high school playgrounds and onscreen. For we now have the wild west of online misogyny.

A counterpoint to that is a growing shift among young women. Birth rates are falling - an interjection of “too hard”, and a de-shaming of celibacy. There are battle cries online, memes and messages highlighting uncomfortable truths in the post #MeToo era:

Women’s swimsuits are built like dental floss, but men’s are built to do things in and even have pockets.

This race must be familiar for many women: she’s overqualified for the promotion, he’s unqualified, yet it’s still a contest.

It’s all fuel, for both genders. And it feels worse to be a teen, now, than when I was growing up.

Yet as I watch this school concert I feel a sharp pain for those boys, too. For their fragility and bewilderment, hurt and rage, that they feel the need to make their presence felt in such a way. There’s a wounded belligerence to it as well as an awareness that untrammeled testosterone is seen as a bullish liability now, not a strength. How has it come to this? Young people, of both sexes, hurting in different ways. Careering so fast towards an adult world they barely understand.

Twenty-odd years ago I wrote a book calledThe Bride Stripped Bare, a novel of brutal honesty about a woman’s sexual complexity. It got women talking; they said they felt heard by it, validated. Bride spoke to the men around them too. I hadn’t been able to tap into the dynamism of that kind of writing again, for a very long time. Truth be told, I’d lost my confidence. Almost gave up several years ago. I’d stopped having sex with my husband in the bewildering tumult of menopause and had lost one of my best friendships in a reeling ghosting and was facing the hormonal rush of teenage children and the deep tiredness of juggling parenthood and work; my professional world was caving in.

The elixir of self-belief had vanished. And that flinty sense of confidence empowers us, to break through, achieve, get. A lack of self-belief in females is an exercise in self-erasure. I thought I might never write novels again. That maybe it was time to … slide away. What had happened? I wasn’t sure, but I’d lost the will, the grit. Couldn’t tell anyone of the humiliation, the failure I felt. For several years I sat on the idea of Wing – after selling the proposal to my publisher – and couldn’t begin.

But then I went to a regional writer’s festival, and several readers came up to me; they had various books I’d written over the past decades held in their memory. I listened, gobsmacked. I had lost self-belief, as girls do, as women do, but a flame was again lit. It also helped that I went away and slept; rested at last.

Then I sat down, and began. Knew exactly what I wanted to write about. Females, in the complicated now, and the males who surround them. The trajectory of the female condition from sparky, self-assured childhood and raging adolescence onward, into a sexual world, where young women are told to be something else; someone else.

Bride had a crackly kind of force. I felt the same energy writing Wing. The honesty and reckless fearlessness in the face of almost giving up. This new novel feels like an encapsulation of all I’ve absorbed about womanhood in the two decades since Bride. When I settled on the writing, finally, the words came fast and sure, just as they had with Bride. That was written in three months, this one five.

I can see the big picture of my career now. An examination of what it means to be female at different stages of life. The writerly tuning forks are Deborah Levy, Elena Ferrante, Annie Ernaux – questing women, continually examining the female arc with an audacious, uncompromising honesty.

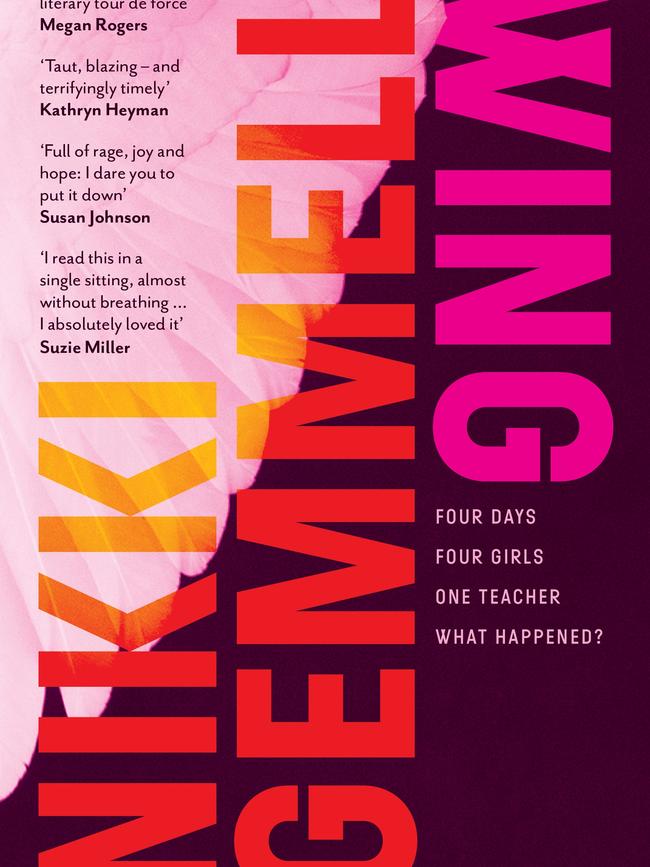

The premise of Wing: Four girls. One teacher. Four days. What happened? The idea was a contemporary, feminist take on Picnic at Hanging Rock with a dash of Promising Young Woman. A group of schoolgirls are on a bush camp. Four become separated; a male teacher volunteers to retrieve them. The girls return but the teacher doesn’t. And the four aren’t talking. Will the teacher emerge? What happened? Who’s guilty and who isn’t?

The novel is about gender politics. Generational fractiousness. Complicated, heartbreaking, competitive friendships between women. Teachers, parents, the school gate. The indignities of ageing. The invisibility of older women. The power and fragility of young women – and also the young men around them. Males confronted by the post #MeToo gaze of women; pushing back, roaring.

Wing is also about the battle-weary older feminists looking at the confidence, stubbornness and outspokenness of young women around them; gazing at them with awe, but also with their hearts in their mouths. Hoping it will be different for them, yet wondering if it’s possible.

Teenage girlsare schooled now to recognise unfairness; made aware of questionable orthodoxies in the world we live in. They look at the mindset of certain men, embodied in particular teachers. “To them, he is a man of the Old World,” I write in Wing. “He is the police officer who takes 24 hours to respond to the domestic violence call – then arrives to find the woman dead. The GP who tells the woman with endometrial pain to have a baby and get over it. The male gynaecologist who insists on the unnecessary examination. He is the tradie who tells a girl in the street to Smile, love, come on, it’s not so bad – but it is. He is the airconditioning that’s a setting too cold. The elbow claiming the plane’s middle armrest. The men’s shampoo and deodorant that are cheaper than women’s – yet guys earn more. The drugs designed for male bodies. He is the car safety features tested on men and men only. He is the judge diminishing the sexual assault case. The bloke who chokes and slaps and shocks. The one who controls. Who ghosts. The one who cannot get a girlfriend and taunts women online. He is testosterone, the hormone of competition and dominion. He is the insecure alpha as opposed to the confident beta and the man who will not stop, will not rest, until he’s colonised and controlled and triumphed.”

Young women are learning to see through it. To understand codes of control; to recognise the ingrained ghosting and gatekeeping that’s gone on for millennia. But have we gone too far, too fast, and are the young men among us now collateral damage? Are we alienating an entire gender in this ruthless process? Those boys who feel they’re not being valued or understood, who feel like they’re under siege. From teachers, principals, the world around them.

Into the void rush the Andrew Tates of the world, online influencers exploiting a grievous sense of disenfranchisement. The messaging to bewildered young men is that in the natural order of things, women should be submitting to male authority. Sexually available.

Amid all this, there are schoolboys behaving badly. At Adelaide’s Pembroke, an internal system of fines is compiled by a group of student footballers for a list of offences that includes “kissing a whale” and “your girlfriend’s crazy”; another offence involves a racist slur degrading indigenous women. This abomination comes hot on the heels of Victoria’s Yarra Valley Grammar, where female students were ranked as either “wifeys”, “cuties”, “mid”, “object”, “get out” or “unrapeable“.

A hole. An object. A receptacle. A servant. Is this how some men and boys are conditioned to view females, still? And what of those girls with the loudest voices? The audacity to question, the disruptors and interrupters? What of those girls’ trajectories? “Everywhere on Earth, with every day that dawns,” Annie Ernaux wrote, “a woman stands surrounded by men ready to throw stones at her.”

I worry about all young women confronted by the male’s indignation and pushback, and his greater physical strength. How do teachers even police this, I wondered at that school concert with its selective roars that felt almost toxic. You can’t, surely.

A reader of my column in this magazine, Bronwyn Shiels, wrote recently: “Men are scared too. Scared we want too much from them, scared they aren’t enough, scared we will ask them to be our everything.”

Yet what the boys were doing in that concert was eroding the confidence, and self-belief, of the girls. How does that ghosting carry itself in the psyche through life, into career paths and leadership roles and pay negotiations? Self-belief is considered a dirty word, especially when it comes to females, but it’s what keeps us focused on what we really want to do and who we really want to be. It taps into the deep reserves of our inner being, despite the strong headwinds. I know, because a faltering self-belief almost felled me several years ago; I just wasn’t sure I had it in me to write another book.

And so, endlessly, we have complicated, vulnerable, raging boys, roaring at girls. We have influencers like Tate, who are incensed by the power of feminine joy – the power of the collective. Men who want to crush that gleeful female force, for who knows where it will end up and how it will transform the world? A series of Taylor Swift concerts is cancelled in Vienna and three girls are stabbed to death at a Swiftie dance workshop in England’s Southport. This is terrorism, misogynist terrorism. Women recognise this, deep in our bones. The ancient rhythms of it. Hatred of women. Their freedoms. Voices. Aptitude. Collective power.

But there are signs of light – awareness is growing among boys, a will to do things differently; to cede to a fairer world, without toxicity. Men’s mental health expert Dr Zac Seidler writes on X: “The best indicator that things are changing: I’ve had five random emails from Yr 9 to Yr 12 boys across Australia undertaking research projects for school on the future of healthy masculinities.” Growing numbers of young men see it, get it. Want to change it. That change has to come from them. It’s a big ask.

Meanwhile, older women look to younger women and, well, we just want them to fly. With confidence and that rocket fuel of self-belief. Will they be alright? Have lift-off? There’s still the disconnect between what they want to be, and what the world wants them to be. As I wrote Wing I was thinking of all those blazing young women among us. They do not know how much older women have freighted in them as we watch them arrow into their future in a beautiful brave arc; as we watch them, breaths held, soaring into a future accompanied by the weight of repetitious history; as we watch them arcing up and away from us, hopefully free, perhaps, who knows. We can only hope.

Wing (4th Estate) is published on October 2.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout