From barley to bottle: step inside the home of Laphroaig

This remote location in Scotland’s inner Hebrides offers visitors the chance to fulfil a pilgrimage to the home of Laphroaig on one of the world’s best distillery tours. Just don’t forget your coat.

On my first trip to Scotland, I was keen to see a man in a kilt – which I immediately did, upon arrival at the airport in Glasgow. Thrilled beyond measure, I couldn’t help thinking: How’s my luck? Then I saw another, and then a third. It seems they really do wear them like the rest of us wear pants, and – what with their hairy legs and their big sporrans – it truly never gets old.

But we haven’t come to Scotland to see men in kilts, we’ve come to drink whisky. Specifically, Laphroaig whisky, on a distillery tour on the island of Islay.

Now, many of you will know Laphroaig: it’s the name given to the smoky, peaty whisky that comes in distinctive white tubes with black writing on the front (those tubes are about to disappear, for climate reasons, which is obviously a good thing, but you’re still allowed to feel a bit sad.) Laphroaig is made on Islay – pronounced eye-la – off the west coast, and while the process was once a secret, visitors are now allowed to tour the distillery and see how it’s done.

But first you have to get there, either by ferry from Glasgow or by plane. We opted for Loganair, a Scottish regional airline. The stewards wear uniforms with tartan cuffs, and ours was rather droll, suggesting that she would be serving caviar “if time permits”.

THE ONLY COCKTAIL YOU’LL NEED THIS WINTER - THE LAPHROAIG PALOMA

Time never permits. Islay is barely 30 minutes by air from Glasgow. You’re up, and then you’re landing on a runway surrounded by paddocks in which black-faced sheep are grazing.

The gorgeousness of Islay is immediately apparent: we take a straight road into the village where we’ll be staying and it’s all white houses with slate roofs, boggy fields and windy beaches.

We check into the old bakery – it’s now accommodation – and make our way to the pub for dinner. They’re serving a cold-weather favourite – beef-and-gravy pie with a puffy pastry cap – so we have that, and our first whiskies, chosen from a hardback “Bible” that lists about 1000 different kinds.

The next day, feeling only a little dusty, we head to the distillery. Now, the name Laphroaig refers not only to the whisky but to the little valley in which the distillery sits. Our guide tells us that the “aig” on the end suggests that the name dates back to the Vikings, whose tongues got tangled with the Gaelic. It’s an old, old place.

No one can say for certain how long they’ve been making whisky here, but it seems that it started with monks, and flourished in the hands of the Ilich (Islay natives), who produced it illegally for hundreds of years before the taxman came knocking.

The distillery proper was founded by two brothers, Donald and Alexander Johnston, who leased 1000 acres from the laird, or estate owner – not to make whisky, but to raise cattle. Cattle require feed, and barley makes sense, and what is one to do with excess barley?

Make whisky, of course.

By the end of the first year, the whisky was more profitable than the cattle.

In 1815, the brothers officially registered Laphroaig, which is why it says 1815 on the bottles, but remember: that’s just when they started paying taxes. The tradition is much older.

The tour is advertised as from “barley to bottle” and it includes quite a bit of history. It’s fascinating to learn that one of the brothers, Alexander, sold out and moved to Australia, probably just ahead of the Gold Rush. (I haven’t been able to find out what happened to him, so if anyone knows, please write in.)

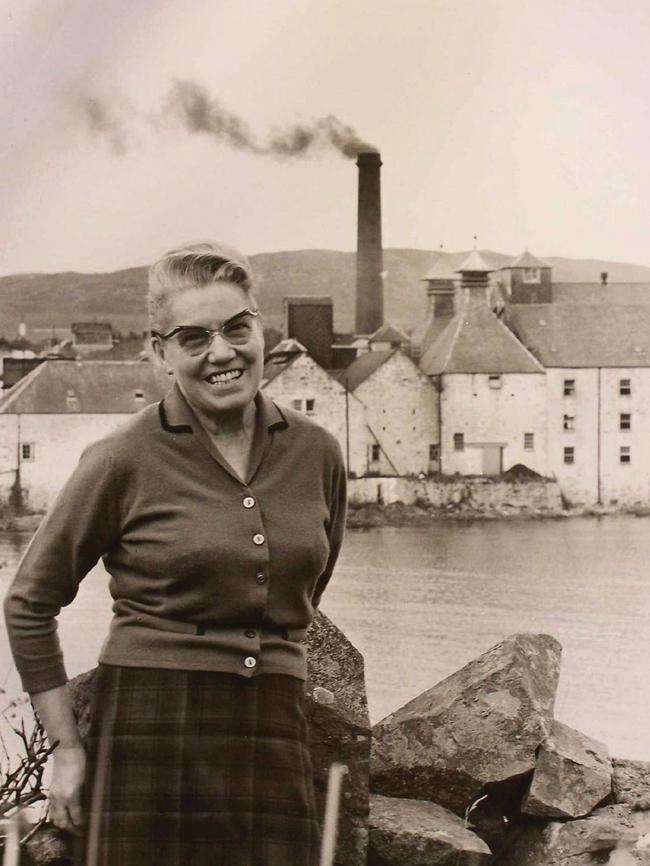

The distillery has changed hands quite a few times this past century – in the 1950s it was acquired by its first female owner, Bessie Williamson, who apparently stepped ashore with only a suitcase, and fell in love. Photographs show her cutting the peat, and hosting dances on Saturday nights.

The distillery is now owned by Suntory, which has committed itself to the history and traditions of the place. This includes soaking the barley (for two full days) with water from the Kilbride stream, which passes through heather and peat on its way to the pipes, so it’s all naturally filtered and fresh.

The malt men then use a chariot – a 1000-year-old piece of technology that looks a lot like a bucket on wheels – to spread the barley over the floor, where it stays for six days. It is important to turn it every few hours (the turning was once done by hand, but they’ve now got a machine they call Tina, and if you think about that for a moment you’ll see why it’s funny.)

The barley must also be smoked, so they light a fire under the floor on which the barley sits, and let the smoke rise into it, but it’s not a wood fire. It’s peat – rotting lichen, seaweed, heather and sphagnum moss. Left alone for 1000 years, it would become coal. You find it under the first few layers of dirt on the island.

Until at least 2019, many families – it’s a small community here, and they all know each other – were still cutting peat by hand. They need quite a lot at Laphroaig, so they use tractors in the peat fields at Machrie Moor.

By chance, there is a chef in our party – a tattooed young gun by the name of Jake Kellie, from the famed arkhé restaurant in Adelaide – and he can’t get enough of this part of the tour. He cooks over open fires in his restaurant and understands better than anyone the way fire will flavour whatever is cooking. He’s keen to cook over peat but it’s hard to find in Australia, and it’s not like you can just bring a slab of rotting seaweed into the country. Customs would have a conniption.

They like to use slightly wet peat at Laphroaig because when you set fire to anything wet, you get more smoke than you would if it was dry, and it’s the smoky flavour they’re after.

From the peat kilns we’re taken to see the copper stills, and from there it’s to the warehouses, where the spirit is stored until it becomes whisky. It’s here that we get our first taste of the product, in a lovely dusty room full of casks, including one signed by a certain Charles, who visited in the 1990s. He is now King.

At tour’s end, guests are invited to become a “friend of Laphroaig”. If you decide to join, they will give you a lifetime lease on your own square foot of land on Islay. They’ll also give you some coordinates, and a pair of sage green gumboots, so you can tramp out to find your plot and plant a little flag with your name on it. You’ll be able to collect annual rent on this plot, in the form of a dram, whenever you visit.

I don’t pretend to be an expert on any of this, but I learnt many new terms during the tasting, most of which will be familiar to those who do know their whisky: we are offered samples from the famous 10-year-old Laphroaig and from the “archive” of “legacy bottles”. It’s a thrill to take a sip and listen to the waffle: they speak of caramel flavours, and ice-cream wafers, peppery smoke, citrus and spice, red berries and cherries, olive brine and pineapples, and I’m not sure I can taste any of that, but gee I feel lovely and warm.

Beyond the distillery tour, there is so much to do on Islay: there are three old castles to admire (two are derelict, and one is an Airbnb). There is a Celtic cross that dates to 800AD, and an ancient cemetery to roam around. There are herons, seals and otters, and caramel-coloured Highland cows with shaggy heads. There is a striking, square lighthouse, raised in 1832 by the Laird of Islay, Walter Frederick Campbell, in memory of his wife, Lady Ellinor, who died at age 36. On a good day, you can see the neighbouring island of Jura, where George Orwell wrote 1984.

We hired Colin, a local guide in a tartan flat cap, who amused us all day with his many sayings:

“If these walls could talk, they’d slur.”

“Today’s rain is tomorrow’s whisky.”

“There are two temperatures on Islay: it’s either cold or bloody cold.”

He also tells tales about the ghosts that are said to haunt the distilleries – there are nine on Islay – and the fairies that live in the peat moss. Has he seen a fairy?

“Aye,” he says. “I’ve been drunk enough.”

There are Bambi-style deer in the fields around Laphroaig, and venison in the pub. There is essentially no crime.

Colin says there was a murder once, back in the 1970s, but it seems even that could have been an accident. We try haggis at the golf club, and whisky a thousand different ways.

Some in our party decide that they prefer it straight, but since I now know how well it plays well with other flavours, I have mine in a mojito. I would recommend it.

Some other tips: take your coat! We went in June, when it was summer in Scotland, but trust me on this: take your coat.

Go to a pub. Most have open fires and you’ll be able to watch the mist rolling in from the sea, as per the song.

Bring your credit cards. They don’t take cash at the airport, and it’s frowned upon in many shops. Like an old person, I had some pounds in my purse, and it was as useless as … well, pants on a Scotsman. Which brings me to the last question I had for Colin: is it true what they say about what Scotsmen wearunder that kilt?

It is. Apparently. Because of course I didn’t ask anyone to show me. I took them at their Hebridean word.

Stake your claim:Claim your own square foot plot of land at Islay by becoming a Friend of Laphroaig: laphroaig.com/friends-of-laphroaig (it’s free).

Do: Join a tour of Islay from “barley to bottle” and learn how Laphroaig uses peat and smoke to make its whisky: laphroaig.com/tours-and-experiences; from $160 for a 2.5-hour tour.

Eat: Join chef Jake Kellie at arhké in Adelaide for a special series of dinners starring 12 international chefs over 12 months; arkhe.com.au/arkhe-friends

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout