Everybody’s Oma: ‘therapeutic diary’ of a mother’s Alzheimer’s journey goes viral

As his mother’s world shrunk through cognitive decline and Covid, Jason van Genderen started capturing her small moments of joy – and the story resonated around the world.

Although she was an online celebrity, Puck van Genderen’s later life was a mix of wonder, confusion and, for a time, loneliness. The matriarch of a small, adoring family, she was an active woman grappling with widowhood and living alone when she was diagnosed with vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease seven years ago. By the time Covid arrived in her ninth decade she was gratefully living with her son Jason and his young family, but even their presence was not quite protective enough. As Puck’s world shrunk during lockdowns, so did her memory.

Despite being told repeatedly about a new virus, she could not understand why it kept her at home and away from the supermarket. So Jason decided to bring the world to her. With his mother denied the familiarity of the shopping trips, coffee outings and walks that had marked her daily routine, he began to recreate some of her favourite things. A passionate filmmaker, he had already started recording his mother and her ever-changing perceptions on his phone. Now, with his partner Megan, he created a faux boutique at their shared home so that Puck could retain some of the joy of clothes shopping. He even set up a supermarket in their lounge room so she could again experience her weekly ritual of buying seven bananas and boxes of Rice Puffs.

When he filmed her response, his mother could still enjoy the absurdity of this act of love. “Ha ha ha, you have to take a film of that,” she laughed in the early weeks of the national lockdown as she wheeled her walking frame around the family’s Central Coast living room, where her favourite products had been carefully laid out in front of a Coles sign. At a time of so much misery and uncertainty, Jason posted footage of the delightful at-home outing on Facebook, including his mum’s big kiss at the end and her satisfied declaration of “lovely” in her still heavy Dutch accent. The footage went viral, viewed dozens of millions of times around the world, and led to multiple more clips.

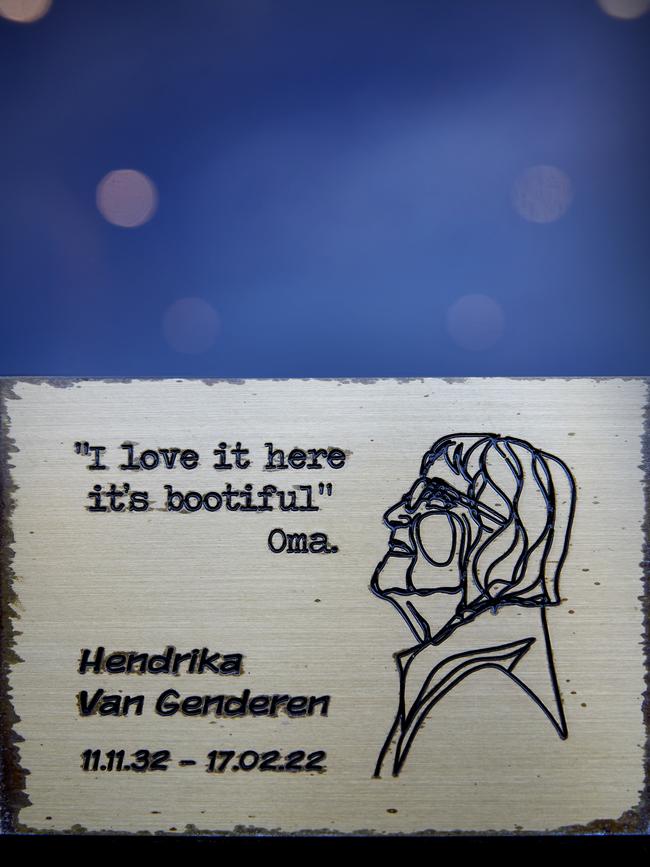

And that’s how Hendrika van Genderen (known as Puck), mother-in-law, grandmother, fierce hugger and lover of Santa Claus and fast cars, became perhaps the world’s most closely watched case of Alzheimer’s, exuding a sense of wonder and joy with her endearing refrains of “beautiful” and “fantastic” even as her own mind slowly disappeared.

Before dementia blunted the edges of her persona, Puck was a charming, energetic woman who walked quickly and lived passionately. Born in the Netherlands on Remembrance Day in 1932, she moved to Australia in 1955 with her husband Jan, who had served in Indonesia with the Dutch army. In Sydney she laboured in a singlet factory and at a plant making chrome bumper bars before eventually setting up a family home on the NSW Central Coast. “She was the ultimate warm-hearted matriarch. Whoever she met she would always greet them like she knew them forever,” says Jason, 50, sipping tea on his shaded back patio at Forresters Beach, north of Sydney. “She was always gregarious and social and loved the neighbours and was always the woman in the street helping everyone else with the gardening.”

Puck was so demonstrative that “people would sometimes say she even hurt a bit when she hugged them”. Social with neighbours but otherwise without an enormous friendship circle, she and Jan had no extended family in Australia, and Jason grew up deeply attached to his mother in particular. “She was everything,” he says, recalling even teenage years when he would sometimes reach for her hand. “I clung to her.”

But about a decade ago, parts of his mother’s shining personality started to fade. Her husband Jan died in 2011 and, alone with a cat in their familiar but large family home near Lake Macquarie, Puck became forgetful and started to fall. Although she managed to mask the changes for a time, Jason was concerned enough to reduce his working week to four days so he could spend Fridays with her.

But her decline didn’t halt, and by early 2016 Jason and Megan were actively seeking a family home with space for Puck, who by then had been officially diagnosed. “We knew that we would create some continental shift by moving her,” says Megan, an affable mother of two preschoolers, “but she couldn’t stay at home and she didn’t want to enter an aged care home.”

In February 2017 the extended family moved into a bright split-level house with a pool out the back and a granny flat to one side. Jason and Megan filled the self-contained unit with some of Puck’s most familiar possessions (her floral couch, a crocheted curtain at the glass front door), and in the midst of caring for their young family and a dog, they determinedly set out to fix whatever holes appeared in their matriarch’s life courtesy of Covid restrictions and her failing mind.

“We needed to do something about restoring her routines,” says Jason of the decision to set up a mini supermarket on their living room bar. “Not going out to do shopping was something we had to talk about 50 times a day.” Puck used to love visiting the aquarium at Darling Harbour in Sydney so for Mother’s Day in 2020, with the help of his two older children from a previous marriage, Jason projected underwater images onto their home’s windows, creating an enchanting outdoor cinema in the courtyard, where an enthralled Puck sat and watched in wonder. But the following morning, as her son patiently interviewed her, Puck could not recall the event. “You get to the point where the hole is getting bigger and you can’t fill it fast enough,” he says of his family’s efforts to accommodate his mother’s ever-decreasing abilities.

The initial supermarket video was posted online early in the pandemic for friends (“everyone had cabin fever, everything was terrible”) and its success spawned more videos, a hugely popular Facebook page with tens of thousands of international fans, a podcast, and eventually a documentary. “It was therapeutic for people,” says Jason, who was interviewed several times on US television about his family’s sunny attempts to isolate with an elderly relative with dementia, offering her everything from nail-painting to pot-planting. “Initially it was ‘we can create a little experience here and we can play it back to her’.” As outside interest increased, he opted to make more videos. “I had the need to still be relevant as a storyteller and I felt the story that was happening at home was worth capturing.”

But Puck quickly regressed in lockdown. “We ended up locking ourselves in the house with her. We couldn’t even do shopping because she would be at the window going, ‘You’re going out. Why can’t I go with you?’” says Megan. “It would have been easier to tell her that there was a war because you can’t see a virus.” By July 2020 she’d had multiple falls and been hospitalised three times in a year.

With each level of decline her family adapted. When reading became challenging, they used pictures instead of words on her shopping list. So she would not keep leaving the house and falling, they reluctantly removed her keys and eventually placed a lock on her door. But her decline kept outpacing them. Soon her vocabulary was shrinking, she became increasingly confused and uncharacteristically anxious, and it was becoming harder to find the lighter moments that had radiated through the earlier videos. “We started something,” says Jason, who was busy replying to an ever-increasing number of online fans eager to know more about his mother’s wellbeing. “And then I thought: what’s the end point of this? Does this finish?”

Faced with a sick mother and a mostly well-intentioned audience who would send Puck cheery messages when she appeared to be down, his footage assumed a heavier tone. “We started showing the tougher stuff, too, because that was part of the journey,” says Jason. He was guided by three rules in determining which footage to show when his mother could no longer make decisions for herself. Was the footage made with love? Would it educate people about dementia? And would Puck, when her cognitive abilities were sound, have approved?

Yet even when all the answers were affirmative, some of the material that made its way to the public was confronting: Puck, without her false teeth, confused in the middle of the night; her face badly bruised after a fall and telling her son encouragingly, “I’m always a very good healer”; sitting at breakfast in her dressing gown after another fall, her head bandaged. “That’s the hardest thing,” Jason says now of releasing those intimate moments when his once carefully groomed mother was looking anything but. “We needed to be able to say that there was a difficulty and a struggle to her journey.” While there were many more bruises that were not filmed, “those things to us became symbols of her strength and resilience”.

So he kept filming, even as he ran to his mother in the middle of the night with a first aid kit after yet another fall. “The camera is like a therapeutic diary,” he says of his own confessionals which, with the footage of his mother, feature in a new documentary Everybody’s Oma. “Sometimes picking up that camera [phone] was like having an anonymous counsellor that was just sitting on the lounge and listening.”

One night Jason, phone in hand, found his mother deeply troubled. “Where is Jan?” she asked him fearfully. When Jason told his mother that her dear husband had died nine years earlier, she plastered her hand across her mouth as though learning the news for the first time. “Gosh, that is unbelievable,” she said, shocked, as she returned to her granny flat and later spoke to a photo of her late husband. “Hello schat [darling]. Today I was all upset. I thought I missed you. And I couldn’t find you anywhere.”

The experience was heartbreaking for Puck’s family who, like their matriarch, were slowly losing control of their lives. Puck’s constant falls and diminishing abilities meant they were now taking care of almost all her needs, from cooking to dressing. While Megan was swamped caring for the extended family, Jason was also troubled by the belated response of some viewers. Overwhelmingly supportive for a long time, some were now critiquing his manner of caring for his mother, who had started confusing him for her father or husband.

“I’m not intentionally being harsh or cruel,” Jason later posted on Facebook as outsiders questioned why his mother could not eat when she wanted, or insisted that she not be left alone. “Her care is our central focus and our choice of language with her is based on a number of preferences.”

Jason installed a security camera in his mother’s unit for safety, but instead found himself watching it almost constantly and waking up each morning fearful she had died overnight. Eventually, he and Megan began sharing night duties attending to Puck. Exhausted and overwhelmed, they reluctantly decided they needed help. In June 2021, Puck, her timber buffet and her floral lounge, her chocolates and her framed photo of Jan, moved into a nursing home for high-level care. The following day Sydney went into its second protracted lockdown.

With her cat, which was allowed to go with her, Puck remained largely isolated in her new and unfamiliar environment for 107 days. For a long time her family could only see her through a window. Physically separated from them, she became increasingly frail and lost weight even with the best of care.

“Someone said to me once that you have to be able to experience all the human emotions to stay sane, to maintain your sense of identity,” says Jason. “I think [for] a lot of people in the confines of lockdown, even when they were cognitively well, your will to outlive that lockdown is hampered because you don’t have this connection with people anymore. You’re not conversing. You’re not connecting. It’s very hard to maintain the will to survive when everything around you has changed.”

After many long weeks confined to the nursing home Puck could finally see her family again but she could no longer recognise her son. She died from a bowel obstruction in February, aged 89. “We would have loved to have been able to keep her at home,” says Jason, “and we changed our whole life to try to make that happen.”

A year since his mother moved out and months after she died, the house is full of children’s toys, but whenever the phone rings there is still that lingering anxiety that it might be about Puck. “I miss the smell of her skin. I miss her space. I miss all the awkward questions she would ask. I miss performing the role of her son or her father or her husband, or being relevant to her,” says Jason, who is comforted by the significant digital legacy his mother left behind – and one enduring trait in particular. “She always reverted to kindness,” he says proudly, “even when she wasn’t understanding the people or the circumstances around her.”

Everybody’s Oma screens at the Sydney Film Festival (sff.org.au) today and tomorrow and in cinemas nationally later in the year.

★★★★: Read our film review of Everybody's Oma