The regime under that daily little pill didn’t last. I hated what those two synthetic hormones did to my body. Could feel them changing it – it felt like an affront. They were muting all the wildness and irregularity, controlling my physiology in a way I didn’t quite trust. Something stern, powerful and bland was taking over, introducing me to depression and doubt. The very fibre of my being felt invaded.

So I stopped. To get back myself. I’d actually read the long, long list of possible side effects, which raised questions; plus there was the niggling question of Hang on, why does the female have to shoulder all the medical risk here? I’ve used, ever since, a combination of birth control options, which have worked through various boyfriends and a 25-year marriage.

There were condoms, which no sexual partner ever complained about. There was the rhythm method, explained by a nun. (She had, intriguingly, an astonishing knowledge of her body; said she could feel herself ovulating whileshe was at the kitchen sink doing the dishes andI’m still in awe of that.) There was also a tracking of the female body’s powerful cycles through four babies, as I learnt to predict the times of ovulation. Knowledge was power – and control over contraception. It all worked, beautifully, without any need for synthetic hormones.

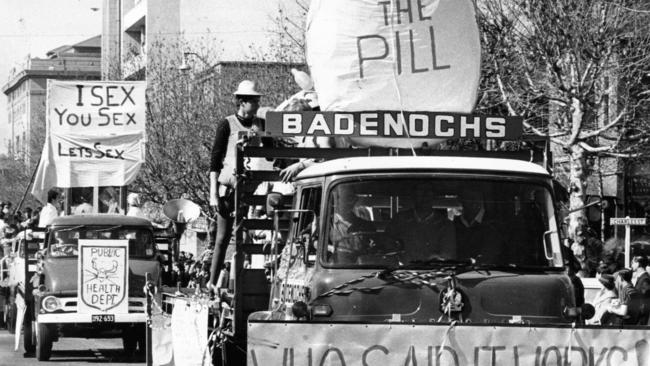

Oral contraceptives and I just didn’t gel, and I assumed I was an outlier in this pill-shy stance. That miraculous little tablet burst onto the world stage in 1961 and heralded a feminist revolution; women could finally take control of their own fertility. But now, increasingly, younger women are saying no to the pill. Guided by TikTok and Instagram, it’s being perceived as a fix-all without proper, rigorous research behind it, in an environment increasingly aware of the male bias that’s shaped modern medicine. One young woman told the UK’s Sunday Times: “There’s no research, they put women on [the pill] really young because they can’t be bothered to fix our actual problems … the pill is just being used to ignore women’s health.”

The stats on waning intake don’t lie. In Australia, in 1992, there were roughly 80,000 contraceptive pill prescriptions per month. In 2021 it was down to 33,500. A recent poll found that 77 per cent of pill-using women surveyed for a UK documentary had experienced side effects such as lowered mood, weight gain, headaches, a lowered libido (!) or breakdown.

Alternatives are coils and implants, but birth control apps have also taken off in a big way. These track a woman’s cycle so she can avoid having sex while ovulating – something my lovely nun, most mysteriously, knew all about. Then there’s the Natural Cycles app, which monitors a woman’s body temperature to predict when she’s ovulating.

Kate Muir, author of Everything You Need to Know About the Pill, believes that the future of contraception lies within the brave new world of fem-tech startups and women-led innovation – with pills individually tailored to a woman’s needs, rub-on contraceptive gels for men and once-a-month tablets. I tip my hat to the exhilarating sexual revolution the pill enabled, but personally, I’m not a fan – because of the effect it had on my own body. There are other ways. Apologies to mum.

It was a hated little thing. It came into my life soon after I lost my virginity (a bleak act, of bewildering loneliness.) The next morning I declared to my mother that the deed had been done, finally. She was celebratory and brisk (a thoroughly modern single mother, who had The Joy of Sex and Linda Goodman’s Sun Signs on her bookshelf.) And so her 18-year-old daughter must be put on the pill, immediately, in honour of becoming a woman at last. It’s what responsible mothers did. I was bundled off to a doctor, and so it began.