Clarkson’s Farm: ‘Everything that could go wrong has gone wrong’

In the six years since Jeremy Clarkson’s tree change he has utterly failed to make a profit on his farm, aptly named Diddly Squat. But now he has a cunning plan.

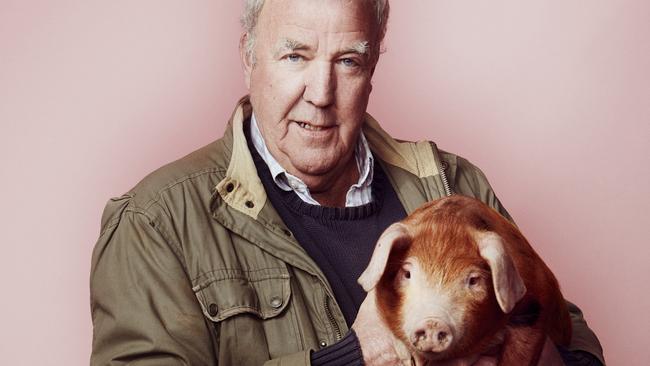

He once claimed his only talents were driving fast round corners and shouting, but as a pig farmer Jeremy Clarkson has found his calling. He has changed the nickname of his Oxfordshire farm from Diddly Squat to Piggly Squat in honour of his new herd of swine and he’s cuddling one now as he poses for a photographer, whispering to it – not shouting – as if it’s auditioning for Babe. “Pigs are my favourite animals we’ve had on the farm by a long way,” he coos to the animal, a female. “I know that cows are great, but pigs are easier to manage and very endearing.”

Clarkson’s Farm, the reality show that follows his efforts to make a living off the land, is back for a third series with the familiar cast of Clarkson, Kaleb Cooper (newly promoted to farm manager), Lisa Hogan (Clarkson’s girlfriend), land agent Charlie Ireland and jack of all trades Gerald Cooper. There’ll be more of the usual chaos, including Clarkson going full Robert De Niro with a hunting rifle, taking medicinal mushrooms and crashing farm machinery into stone walls.

It’s six years since Clarkson fled his Notting Hill penthouse to run 400ha of mixed arable and grazing on the edge of the Cotswolds. Back then, his unsuccessful attempts to turn a loss-making venture into a going concern included rearing sheep (it cost him more to shear them than their wool sold for) and beef cows (the council closed his farm restaurant, making it uneconomical to rear them). Now he has turned his hand to pig breeding in a last-ditch attempt to bring home the bacon. “A cow has one calf, whereas the last bout of births we had, one of our pigs had 14 piglets,” he explains. “That’s a lot of money.”

But life is not all hog heaven. “Behind the scenes, everything that could go wrong has gone wrong,” he growls. The hottest June and wettest March in recent history have wrecked his potatoes and spring barley. His ambitious plan to revive a 1960s government scheme to replace tractors with hovercraft for crop spraying was an expensive flop. And he has fallen foul of regulations at every turn.

If it sounds like a litany of disasters, it is – except it has all added up to one of the biggest TV smashes of the decade so far. In 2019 Amazon commissioned a single season, on a small budget, in anticipation that it might appeal to a niche audience. The Guardian called the series “wearisome, meretricious rubbish”, concluding it would be shunned by viewers. It went on to become the UK’s most watched Amazon-made show. Its series two premiere won 4.3 million viewers, eclipsing the 3.2 million who watched the launch episode of the streaming channel’s biggest investment – a mega-millions Lord of the Rings saga.

Today Clarkson is guiding me around the farm in the spring sunshine, through giant puddles from recent rain. Part of his empire is in an area of outstanding natural beauty, but the soil is not especially fertile or profitable, hence him christening it Diddly Squat in 2018. It lived up to its name, making a surplus of just £114 ($218) in its first year. “That’s a thousand acres, working seven days a week,” he says. “It’s all farming pays.”

How does he explain the show’s unexpected success? “It was an enjoyable way of learning about where your food comes from. Because lecturing people doesn’t work. Television is rather obsessed with organic and diversity and sustainability, rather than where food actually comes from and the actual people who make it for you. The Kaleb Coopers and the Geralds and Charlie Ireland and so on. I think it’s been a very useful program for making people go, ‘Bloody hell, you work very hard doing that and earn no money at all.’”

From the show’s inception Clarkson wanted to reveal the true “mud, blood and barbarism” of life on the land, and pig farming is the starkest example yet. His pigs are a rare Oxfordshire breed called Sandy and Black, misheard by Clarkson as “Shandy and Black” – “sounds like the sort of thing a northern girl would order in a Zante nitespot,” he observed in his Sunday Times farming column.

Spurred on by MP Liz Truss, who in a speech to the Conservative Party conference announced she would soon be “in Beijing opening up new pork markets”, Clarkson resolved to seize new export opportunities. He planned to free-graze his pigs in woods where they’d “truffle about turning up acorns”. “Only in an idyllic Winnie the Pooh world,” warned Charlie Ireland, the farm’s resident voice of reason. “Pigs need round-the-clock care.” And so it transpired – as we see from Clarkson’s ham-fisted efforts. There was a high mortality rate among the piglets from his first litters, some of them accidentally crushed by their mothers.

-

“I reckoned the pigs would provide something that’s sadly lacking in farming today: a bit of genuine happiness,” Clarkson says.

-

“Instead, it was almost unbelievably sad. I’ve never seen Lisa so upset. The film crew looked shellshocked. We had a catastrophically high level of deaths and I was desperately worried we were doing something wrong, but it turned out we weren’t, it was just that pigs are bad mothers – the Sandy and Black particularly so. That’s why it’s a rare breed.”

The series doesn’t flinch from the day-to-day grimness, along with the frustration of creeping red tape, hence it striking a chord with actual farmers.

Robert Martin, 55, a Cumbrian dairy farmer and national chairman of the Tenant Farmers Association, says Clarkson’s Farm fairly reflects the daily trials and worries faced by his members. “I do watch it and I do enjoy it. Clarkson said he wanted to increase awareness, especially among people in urban areas who maybe don’t really think about where food comes from. Whether you like Clarkson or you don’t, I think he’s succeeded and he’s done it in an entertaining way.”

George Summers and his father, Micheal, farm 185ha of mixed arable and livestock near Melton Mowbray, in England’s Midlands. “I’ve never watched it on principle,” says Micheal, 57, “but I understand there are a lot of people with an entirely contrary view, my son being one.” George, 19, has seen every episode of the first two series and will be watching the third. “It’s very entertaining, even though I think some of it’s done for comedic effect,” he says. “For example, when Clarkson accidentally tipped his tractor up on its back wheels, then got Kaleb to sit at the front as a counterweight, you knew that was unlikely to happen.”

Clarkson and Kaleb won the 2021 Flying the Flag for Agriculture award at the British Farming Awards. Last May Kaleb was summoned to Downing Street to explain to Prime Minister Rishi Sunak why farmers were struggling – a serious message with a comic edge as Sunak did his best to understand Kaleb’s rural brogue. Ireland was there too, admonishing officials over all the form-filling devised by the government. “You need a PhD in grant applications if you’re a farmer,” he told them.

If there’s a narrative thread it’s Clarkson’s own journey from innocent abroad in series one – Billy Crystal in City Slickers, if you like – to horny-handed son of the soil. Now he’s less squeamish about sending his animals for slaughter, even though he confessed “I’ve got guilt” as he transported seven pigs to an abattoir. “You’ve got to eat them to save them,” another farmer reassured him. “That enables the survival of the breed.” Still, Clarkson is uncomfortable with the gallows humour of the slaughterhouse. “The butcher will want everything back bar the squeal,” an abattoir worker joked as Clarkson winced. He was determined to brazen it out, declaring, “This time I behaved more like a farmer and didn’t have any unmanly moments,” but the soundman captured the wobble in his voice.

None of it makes sense unless you’re a farmer, Clarkson admits. “You’re up all night nurturing pigs, trying to make them comfortable, trying to make them alive, then you arrive at the farm shop to receive boxes of pork chops and sausages. There’s only one expression that I can think of and it’s ‘farmer’s logic’. All farmers love their animals, then they kill them and sell them.”

In the new series the light relief comes, as ever, in the form of Clarkson’s incompetence with farm machinery – witness his Chaplinesque attempts to harvest nettles, in which he becomes ensnared in the machine and falls into a thicket. He converts an air-sea rescue hovercraft to spray highly corrosive nitrate fertiliser. The dangerous task requires a protective hazmat suit, so he recruits Kaleb to help and chaos ensues as the hovercraft careers out of control.

He’s still in dispute with West Oxfordshire District Council, which, as well as closing his restaurant, refused a car park for his farm shop. But now he has powerful allies. Sunak pledged recently to free British farmers from burdensome red tape when converting barns into shops and opening restaurants as a means of reducing dependency on agricultural subsidies.

Under a government-backed rule change dubbed “Clarkson’s Law”, farmers will in future no longer need to seek permission from local councils to repurpose farm buildings, making it easier to sell their produce to the public.

We’re in the kitchen of Clarkson’s hilltop house, which has sweeping views over sheep-cropped hills and yellow stone houses. His dining room table, as long as a station platform, rests on replicas of the Brunel arches at Paddington station. Recessed into the table top is a Hornby 00 model train track. Clarkson shares with Rod Stewart a love of railways. Lisa Hogan is bustling about looking for a model train. “What would you like?” she says, rummaging through Jeremy’s collection. “We have a GWR locomotive, we have the Flying Scotsman.”

From a walk-on part in the first series, Lisa, an Irish-born former actress, has moved nearer to centre stage as she gets to grips with running the farm shop and selling cow juice (milk), bee juice (honey), Jeremy’s Juice (jam) and Jeremy’s Hot Seed (mustard). At one point there’s an unresolved hint of her and Clarkson tying the knot. “I’ve got a big surprise for you,” Clarkson tells her as they walk through a field. “Is it a proposal?” she asks. Clarkson pretends not to hear and shows her the surprise – a fallen willow tree bursting back into life. She presses him. “I’ll think about the proposal, OK? I’m not ready yet.”

When I ask her about the exchange, she laughs. “I just thought I might surprise him.” Did she make a leap-year proposal of her own on February 29?

-

“Jeremy doesn’t think I proposed but he wasn’t wearing his hearing aids, so no one will know.”

-

Clarkson’s Farm is part soap, part serious. One thing it tackles is the problem of soil depletion, which Clarkson warns is a threat to world food supplies as serious as climate change. There may be only “ninety to a hundred harvests left before the topsoil is dead,” he says. The global amount of arable land per person in 2050 will be a quarter of that in 1960, according to the UN, as populations grow and soil degrades. Chemical-heavy farming methods and deforestation are among the culprits.

With this in mind, Clarkson teamed up with Andy Cato, one half of the dance music act Groove Armada and a keen organic farmer, who arrived with a plan to help Clarkson rejuvenate his soil. This involved growing beans and clover in the same field as wheat to boost vital levels of nitrogen. The idea worked better on paper than in practice, but if success is the ability to lurch from one failure to another with no loss of enthusiasm then Clarkson embodies it. Each of his hare-brained schemes – making soup from nettles, or jam from blackberries sucked from a hedge with a vacuum cleaner, or venison sausages from culled deer, or a pick-me-up from powdered mushrooms – is solemnly appraised by Cheerful Charlie, who turns up like a stern bank manager to put a leash on Clarkson’s enthusiasm and remind him of food safety or stock-rearing regulations.

Clarkson’s instinct is to challenge officialdom in the manner of Kevin Costner’s hard-headed rancher in the TV drama Yellowstone. “Let’s fight the f..kers and hammer them into the ground like tent pegs,” he says at one point. “I’ve been watching Yellowstone. When someone displeases them, they murder them, take them across the state line and throw them in a ravine. I’ve been looking at that scene a lot.”

Is there a danger, I ask, that the series could slip into a cliché of the struggle between honest, hard-working locals and meddling bureaucrats? After all, life in the Cotswolds is hardly a back-breaking slog for many of its well-heeled residents. The list of local luminaries includes David and Victoria Beckham, music mogul Simon Cowell, former PM David Cameron and his wife Samantha, and Alex James, the cheese-making bassist of Blur.

We catch occasional references to the moneyed set in Clarkson’s Farm. Clarkson hatches a plan with Kaleb to sell hay to newly arrived townies who may be planning to keep horses. Meanwhile Lisa tries to entice them by “inviting her thin, blonde Oxfordshire friends over for a spot of goat yoga”, as Clarkson puts it – an exercise class she holds inside a goat pen.

The epicentre of the smart set is his arch rival, the posh Daylesford farm shop – imagine Country Life magazine as a retail outlet stocked with wholesome organic produce. Clarkson delights in undercutting its prices in his own farm shop (“It’s £7 in Daylesford,” he gleefully tells Lisa as he prices his Hot Seed mustard at £6).

Covid accelerated the exodus of wealth from London. “When I moved to Chipping Norton about 30 years ago it was a small market town with a population of 5,800,” Clarkson says. “Today it’s still a small market town, but the population has skyrocketed to 9,400.” Kaleb admits that spiralling local land prices have put a crimp in his own ambitions. “My eventual goal is to own my own farm,” he tells me. “The only problem is the price of land. Around here the average farm is £3 million.”

If he wasn’t earning money from TV, presenting Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? and The Grand Tour, and writing newspaper columns, Clarkson admits his farm wouldn’t be viable. “I’m in the fortunate position of having other income streams,” he says.

Aside from the knockabout, there’s another side to Clarkson’s Farm. It’s as lovingly filmed as an Attenborough wildlife documentary, with lingering shots of hares and deer running through meadows and red kites hovering. There’s a joyful moment when Clarkson’s cows are returned to a meadow from winter captivity. “A lot of the time farming is brutal and hard,” Clarkson says. “But at this time of year, when everything is vivid and growing and bursting with life, and everyone is well, it can be the best job in the world.” b

Clarkson’s maddest machines

JCB Agri Super telehandler, $192,000

I went for 59 years without a telehandler and I have no idea how. It has a telescopic arm that can lift and move heavy loads and it’s as cool as the kit on Thunderbirds. They are the Swiss army knives of the farm. I once used it to transport crates of empty bottles, and although it’s me we’re talking about, I didn’t drop one. You can also drive it to the pub. How did the world work before telehandlers?

BHC twin-engine hovercraft, from $48,000

I like hovercrafts; this one was a former air-sea rescue machine. We tried it for crop spraying. A tractor leaves wheel ruts in a field where nothing grows afterwards, but a hovercraft doesn’t, so you get better coverage. The trouble was, it couldn’t cope with any kind of gradient or, as it turned out, any kind of weight in terms of the liquid fertiliser spray. So, tragically, the hovercraft was abandoned.

Kobelco mini-excavator, from $102,000

I don’t think there’s a man alive who wouldn’t have fun with a digger. Go and make a pond. No, make a trench.

The first four episodes of series three of Clarkson’s Farm are on Amazon Prime from May 3

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout