Jeremy Clarkson opens the gate to Diddly Squat, his Cotswolds farm

He’s a petrolhead who traded top-rated TV for a loss-making farm. Does he regret the gear change?

During the centuries in which sheep have occupied the countryside, man has rounded them up by traditional methods. The farmer enters the field with his dog and the sheep run to a distant corner. The farmer whistles and the dog herds the sheep to where they’re needed. It’s always been done like this and sheep have every right to expect it always will be. So when Jeremy Clarkson arrived in their field with a remote-control drone that made barking noises, who could blame them for scattering in all directions?

Flying the drone low, Clarkson chased them across the field towards the farm gate. For a while the experiment seemed to be working and he imagined being able to sit indoors, out of the cold and wet, rounding up sheep in the way that operators of Predator drones patrol the skies of Afghanistan from Nevada.

Quickly the animals realised that, unlike a sheepdog, the drone had no teeth. Once they got used to the noise of the rotors they resumed munching without so much as a skywards glance. “They were completely unfazed,” says Clarkson. “They just ignored it.” No amount of dive-bombing or electronic yapping from the airborne sheepdog would bother them. “They just looked at me with gum-chewing insolence as if to say, ‘Why is that idiot flying that drone?’” It was one of many experiments Clarkson has tried in an effort to turn a loss-making farm into a going concern.

For more than three years he has worked the land in Oxfordshire, trying to balance the books on a farm he renamed Diddly Squat because “that’s how much money it makes”. He has ploughed, sown and harvested in what he concedes is not richly fertile soil. He has reared livestock and gathered eggs from free-range hens. He has planted cover to attract game birds and created ponds to breed fish. He has built a farm shop and a bottling plant for spring water.

Things haven’t gone to plan. Some of his crops died from fungal disease and insect infestations. He was told his farm shop breached planning and Covid regulations. His bottling plant became contaminated. When pubs closed during lockdown, brewers stopped buying his barley. Hundreds of trout he hoped to sell to restaurants were eaten from his newly dug lake “by otters or cormorants or herons – or all three”. He was chased by bees.

When he tried to clear woodland, his chainsaws jammed in the tree trunks (“At a rough guess I’d say that 20 per cent of the trees in my woods have chainsaws stuck in them”). He bought a new tractor – a Lamborghini – and managed to drive it “into six gates, a hedge, a telegraph pole, another tractor and a shipping container. I think I’m right in saying I have not completed a single job without at least one crash.” All of that while being squeezed by rising costs and weak food prices. To illustrate the problems, on the day I visited a fox got into his henhouse and killed his 36 prize egg-layers.

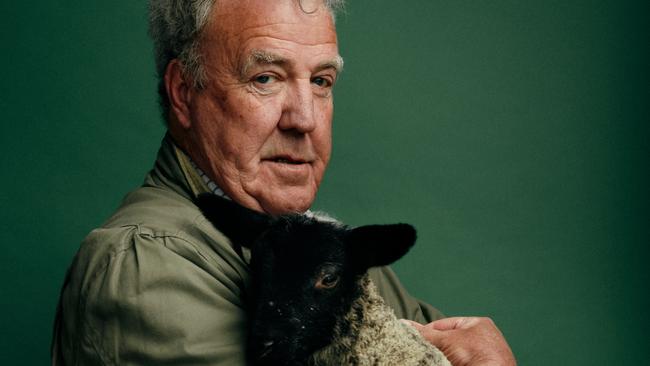

The sheep have caused the most trouble. He started with 75, including two rams named Wayne Rooney and Leonardo DiCaprio, and the flock now has 130 lambs. He compares them to delinquent teenagers; they broke through an electric fence into a neighbour’s field, so he replaced it with wire mesh – and they got tangled in that. When he tried last year to shear the ewes, they put up such a fight “it was like trying to turn Jean-Claude van Damme upside down to cut off his mullet”. He had to bring in professional shearers, who charged him £1.45 [$2.66] per sheep. The wool sold for only 30p [55c] per fleece. “That’s why the farm is called Diddly Squat,” he sighs.

When we sit down in the sunshine outside his barn he’s wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt – “the only clean one I could find”. Ideally he’d like one that says “A bad day on the farm is better than a good day at the office”. Even with all the problems, he doesn’t regret moving here from London. “I love it for the stolen moments. Summer evenings on a tractor. Leaning on a fence looking at the lambs. In the first lockdown I’d open a bottle of rosé before bed and sit listening to the wood pigeons. God, they were wonderful days.”

He has divided the land under cultivation between traditional staples – wheat, barley and oilseed rape. The biggest area – about 80ha out of 400 – is given over to wild meadows that run in strips through the middle of fields; they attract friendly insects, and agricultural subsidies. He does his best for conservation. “I planted turtle dove mix around the place because turtle doves are on the verge of extinction. There’s a rare hen harrier in one of my owl boxes. And I’ve got a great grey shrike. It may not sound much in global terms but all I can do is look after the postage stamp I’ve got here.” When botanists visited they discovered the wild patches in his fields were “chock-full of kidney vetch, green-winged orchids, yellow rattle and various other things that sound as if they’ve escaped from a Victorian book of diseases”. He has created a wetland area for wildfowl and marsh plants (he may also release a few alligators to deal with unwanted ramblers, he jests).

Following government advice to farmers to diversify and rely less on handouts, he built the farm shop. He proudly shows me the fridge loaded with local cheeses and the shelves groaning under the weight of apple juice, honey, piccalillis and preserves with names like Winter Morning Ginger Marmalade. He sends wheat to a miller and uses the flour to bake and sell bread. There’s a self-service milk machine and branded merchandise, including hats and aprons embroidered with Diddly Squat. He has just restocked after a bumper weekend in which he “sold out of everything”.

“That’s the thing about selling seasonal products on a small scale – it’s inconvenient for the customer. I make a new batch of honey and it sells in two hours. Once I’ve picked the rhubarb there’s no chance of a top-up. I was left with loads of chard because people didn’t know what it was, so I called it spinach and it flew off the shelves.”

He will have to close the shop for two months to replace the steel roof with a slate one as a result of a council decree he describes as “pettiness on an industrial scale”. “That’s OK, though. It makes perfect sense to shut down the business and lay off the people we employ.”

After complaints from “a handful of unhappy locals” stopped him selling teas and coffees, he started a visitors’ book to prove that most customers are from far afield and are not being lured away from local shops. Far from stealing business, he’s creating jobs, he says. He has hired contractors to dig ditches, repair farm buildings and rebuild walls. “We put 20 new hives in last year to make honey. Viktor the Ukrainian bee man is brilliant.”

As you drive south from the Oxfordshire markettown of Chipping Norton and climb to higher ground, the horizon opens up to reveal far-reaching views of the Cotswolds. In the early days he shuttled between his farm here and a penthouse flat in Kensington, west London. Then one day he flew back to Heathrow from a holiday in Africa, drove out of the airport and had to decide whether to turn left to the Cotswolds or right to London. He turned left and didn’t look back. Now he devotes the time he might once have spent reading car magazines to Farmers Weekly.

London friends predicted the buzz of city life would soon draw him back, but it’s easy to see why he fell in love with this area of pretty villages and rolling hills. Even before #WFH was coined he was working from home. “All I have to do each day is pull on a pair of jeans and step out the door.”

More recently the work has come to him. Amazon Prime commissioned an eight-part series called Clarkson’s Farm. The idea was to lay bare the realities of life on the land, as distinct from the bucolic ideal. The truth is that the daily grind is often repetitive and bleak. He’s embarrassed that his efforts have at times been so shambolic. “I’ve done other shows where we’ve messed up for comedic effect. But this time I’ve really tried.”

He vowed at the start of filming he would avoid the kind of sentimentality typified by bottle-feeding lambs, but he ended up bonding with the animals. He nurses a sick lamb and learns how to be a midwife to pregnant ewes (“the whole process is incredibly sweet and incredibly revolting simultaneously”). At one point a gruff farmhand advises him to cull three ewes and he seems genuinely upset. The camera follows him as he drives the sheep off on their last journey. “I don’t know what to say about this mission this morning,” he says. “I’m a sheep farmer and this is what sheep farmers do.” He comes away with tears in his eyes. “This is a powerful advertisement for vegetarianism,” he says later, though he’s not persuaded and declares his own mutton “delicious” after sampling it.

It’s possible, he admits, that he’s in love with a vanishing notion of farming – and may himself be an endangered species. Farmers are governed by rules invented to please environmental lobbyists, he fumes. His pet hate is exotic produce flown in to satisfy modern tastes. “If you’re trying to go for a zero-carbon country, why fly avocados in from Peru?” Much of what’s imported can be grown here, he argues. “Why sit on perfectly serviceable land and bring food in from New Zealand?” To prove a point he recently planted durum wheat, a type grown in the south of France. It thrives in the drier conditions that Britain now experiences. “If that’s what we are going to have in the UK in the future, that’s what we’ll have to grow.”

If all this sounds like Clarkson the climate convert, there are still flashes of the petrolhead of old. Farming has allowed him to indulge his love of machines, such as the barking drone. He spends hours browsing the power tools in his local farm equipment shop. He can’t believe he’s managed to get through the past six decades without owning a telehandler, a heavy-lifting farm vehicle. He has a collection of off-road vehicles that could be straight out of Thunderbirds. He uses a mechanical mole to lay his own water pipes and plans to get a flamethrower to deal with weeds.

The countryside creed of make-do-and-mend appeals to his Yorkshire parsimony. But for all this, he still feels like an impostor next to native countryfolk, even after three years.

On the hillside near his cottage he’s building a celebrity-sized house that may be the last one he ever lives in. It’s made from Cotswold stone hung on a steel frame, a construction method that allows rooms to be bigger. It sounds hi-tech but inside it’s a throwback to the days before digital appliances. He’s installing an Aga and a coal-fired range. “I managed to find one from an old Yorkshire mining house,” he says. He’s repurposing his loss-making wool as loft insulation.

Does he miss anything from his pre-farming days? He would love to have shown the farm to AA Gill, a friend and fellow columnist, he says eventually. Gill died five years ago from cancer, aged 62. Clarkson is silent for a moment, then his phone buzzes with a message marked “Urgent”. It’s the organisers of a forthcoming junket to promote the Amazon Prime show. They want his sign-off for the catering arrangements. He looks at the message with a pained expression. “‘The individual lunch boxes will be Covid-compliant and eco-friendly with bamboo cutlery,’” he reads aloud. He shakes his fist at the phone. “I don’t want quinoa or hummus or avocados. The show is about ordinary farming. I want pork pies, Scotch eggs and beef sandwiches, with proper cutlery. Served from the back of a bloody Range Rover.”

Clarkson’s Farm is on Amazon Prime Video