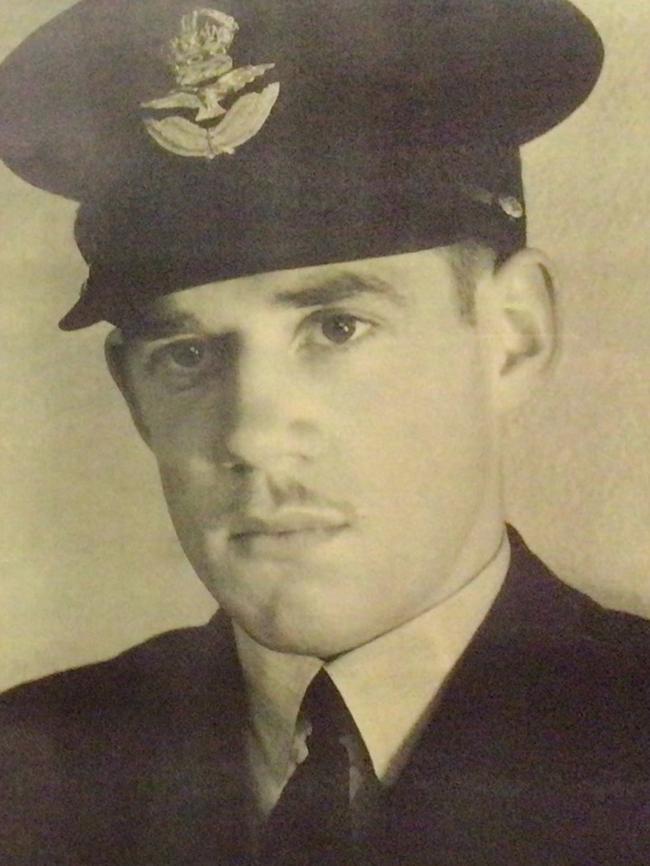

Alan McCormack’s great escape: Australian airman’s extraordinary journey from prisoner of war to freedom

Australian airman Alan McCormack survived being shot down over Denmark, a plunge into the frozen Baltic Sea, and a brutal prisoner-of-war camp, to make it to freedom.

Number 466 Squadron leader Alan Ower McCormack knew he must, at all costs, keep hidden the various accoutrements that British boffins had given him to effect an escape.

He had two escape maps sewn into his shoulder pads, two magnetic buttons on his battle dress, a comb which had hidden two magnetic needles in the thickest part, a knife which had been strapped his right leg and the kit given to all aircrew containing milk tablets, matches, a condom to protect a watch in the event of a sea bailout, concentrated fruit and local money.

But he was lost.

INTERACTIVE SPECIAL: 66 MINUTES OF HELL

In the early hours of January 29, 1944, McCormack had parachuted out of his distressed Halifax bomber plane HX294 over German-occupied southern Denmark in force nine gale conditions, landing in the freezing water in the pitch dark but luckily discovered after some time of being dragged by his parachute that he could touch the sea floor and then wade to shore.

His crew, including one man reluctant to jump, who had to be given an encouraging shove, were further east. The first man out, navigator Jack Tylor of Katanning, West Australia, would be the only casualty of the seven, drowning after landing in the Baltic Sea. His body washed up at Nakkebølle Beach on 16 April 1944 and was buried at a local cemetery in Faaborg two days later.

But at this point McCormack, then aged 24 from Melbourne, Victoria, was unaware of the fate of his crew. He was the wing commander leader of the A team at the 466 squadron based at Leconfield in Yorkshire and feeling the responsibility of his men deeply, he struck out along the shoreline and found a red painted barn storing farm machinery for the local orchard.

Freezing cold, and wearing a sodden battle dress, he ran on the spot to try and warm up, and immediately checked that his escape kit was intact. He hoped the items would help him identify his location and then he believed he could steal a local fishing boat and navigate his way to neutral Sweden.

“I removed my Wings and Rank stripes and put them on the rafters in the shed … if there was no brevet you might get away (from German retribution) for awhile until emotions had subsided,’’ he recounted decades later in a three-page letter to an historian at the Rudkoping Archives in Denmark.

“My first objective was to locate myself. There was a sign post outside the shed on a path with an indecipherable name.

“I cut the lining of my battle dress and removed the escape map, cut a small slit in the matchbox covers and starting from the top worked my way down and across the map trying to establish my whereabouts. Unfortunately the place must have been too small to be printed on the map. I removed one of the buttons from my tunic and balanced it on a match, these buttons had a very small white dot on them which rotated to the north and from there one could ascertained where was north and the other main points.’’

66 Minutes of Hell

‘Your thoughts of living much longer were a bit bleak’

Bill Purdy fought through the most dangerous theatre of WWII as a pilot with Bomber Command. Every time he took off for Germany he stood a 10 per cent chance of not making it home.

How Bomber Command was airbrushed from history

Politicians cancelled the important role Bomber Command played in WWII after a devastating attack on the city of Dresden which killed 25,000 people.

Little-known Aussie became one of the great wartime leaders

‘Brilliant’ Queenslander Don Bennett’s pivotal role with the Bomber Command’s Pathfinders made him one of the Allies’ greatest leaders of World War II.

Danes can never forget Aussie airman’s ultimate sacrifice

Sigurd Sørensen was only seven years old the night Aussie pilot Norm Cooper’s plane went down. The force of the explosion blew out the windows of his family’s farmhouse.

Radical radar breakthrough helped defeat Nazis

Six Bomber Command crews were reportedly ‘thrilled with our new toy’ but despite having a wartime technological marvel on-board none of their planes survived.

WWII hero with a compass hidden in his comb

Australian airman Alan McCormack survived being shot down over Denmark, a plunge into the frozen Baltic Sea, and a brutal prisoner-of-war camp, to make it to freedom.

He added with some dry humour that this was a morale boosting outcome. “It was naturally only general, but I soon found where east was and orientated myself, which after bailing out in the dark the only direction you know is down.”

McCormack’s Halifax had been part of a saturation bombing offensive, the Battle of Berlin comprising this particular overnight offensive of 677 heavy bombers trying to smash the German capital.

Just an hour earlier McCormack had narrowly shook off one annoyingly feared German night raider which had terrorised the formation in southern Denmark on their way to the “Big City”, and he had delivered his payload, two 1000 pounders and two 500 pound bombers as well as some cluster bombs amid intensive enemy fire, the probing cone searchlights and thick flak.

But when the bomb door was open, something hit the fuel lines.

“We were hit in the belly” he would later recount. As he headed north over the German border to the turning way point in Denmark, his engines became troublesome and it was feared the fuel lines had been ruptured.

With two engines gone McCormack decided to make for Sweden, rather than cross the channel, but just as he adjusted his heading, the third engine faltered.

“So I decided to bale the crew out whilst I still had one engine for control,’’ he said. The plane would crash into the Baltic Sea. It has never been recovered although local fisherfolk are believed to know of the location, but have kept it secret from authorities as it’s a good fishing area.

McCormack told of how he landed “in the drink”, came to the shoreline, found the barn and then while scouting the local area, ran into a local boy, who brought him some food and pointed on the map where he was.

McCormack thought he could perhaps steal a fishing boat and try for neutral Sweden, but on the first night of trying he was unsuccessful, not knowing that all of the boats had been requisitioned by the Germans for their own purposes. On the second day in the barn he was astonished and a little angry that the boy returned, this time with a policeman. McCormack was taken to the local town hall, which doubled as a police station, and to the delight of the crowd he threw them his escape moneys.

“Instead of cruising the beautiful Baltic I had to reluctantly and forcibly accept the hospitality of the Third Reich,’’ he said.

His daughter Michele McCormack, who lives in Melbourne, told The Australian the decisions would haunt McCormack, who had always wondered if he had kept going on the one engine what would have happened.

“He wouldn’t have even known then about Jack or when or how the others landed, for that matter. So it must have been pretty horrific,’’ she said.

“It is surprising that those who survived got through it when you think of all the repercussions mentally, emotionally, physically. It is quite amazing.’’

McCormack, whose initial RAAF character assessments included “boisterous, well loved by others, a pleasant chap, and one of a kind,” ended up at the interrogation centre at Dulag Luft where he was removed of his watch, knife and collapsible razor.

“The rest they didn’t find,’’ he said. There he was reunited briefly with five of his crew; English flight engineer Russell Collings; bomb aimer Geoff Walker, of Melbourne, wireless operator Jack Clark, of Dumbleyung, Western Australia; mid upper gunner Sydney Smith, of Manly, NSW and rear gunner Ross Whitfield, of Adelaide before they were sent to Stalag Luft L6 in Heydekrug.

He heard how they too had been rounded up within hours of landing by a Danish population, willing to give food and warmth, but too scared to help with any escape efforts. McCormack didn’t delve into the interrogation methods, other than to note there were “various” methods and he received no treatment for his feet.

But at the Dulag it was known the commandant would deliberately turn up the heating for days with little water provisions so that thirsty prisoners would swelter.

McCormack was then allocated to the prisoner of war camp, Stalag Luft III in Sagan, where his senior rank ensured he quickly met Roger Bushell, the architect of the Great Escape plans, later made famous by the Steve McQueen film of the same name.

In an extraordinary effort the Allied prisoners of war, all aviators, had dug three tunnels in porous sandy soils, going down 10 metres before making any headway under the prison perimeter 100m away, in a bold effort to get 200 men out. Earlier a group of men at the same POW camp had escaped using a Trojan Horse.

The Great Escape plans were well advanced when McCormack came into the camp and he said while he joined the escape committee he didn’t take part in a ballot for one of the escape positions because he hadn’t contributed to the audacious plot others had for months. Instead he worked on a fallback tunnel “George” being built under the camp’s theatre stage.

He handed his silk map, his two secret buttons and the comb with its hidden needles to fellow Australian Albert Hake, 27, and helped the mechanical wizard hand craft compasses and forge documents for the escape. All of the items made it out of the camp with some of the 76 escapees.

The Nazis eventually rounded up all but three of these men on the run and on the orders of a furious Adolf Hitler, 50 of them were brutally executed by the Gestapo. Five of those murdered, including Hake, were Australian.

McCormack was also lucky in the camp to have come across another downed pilot Harold Bjelke-Petersen, who had also done some physiotherapy training.

Bjelke-Petersen, a cousin to Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Peterson, had persistently massaged McCormack’s painful frost bitten feet, caused by the icy escape from the plane, and made him plunge his legs in ice and then very hot water to stimulate the circulation. McCormack believed these actions saved him from a double amputation, but the pain in his legs was to last the rest of his life.

McCormack remained in the stalag, but he was then forced onto a 193km death march from the camp to Lubeck, near the Baltic coast from the end of January 1945 to the end of April. Many of his fellow POW’s died on this dreadful march during one of the coldest winters on record, ordered by Hitler as the Russians were closing in on the camp surrounds.

His daughter said a fellow escapee had told her years later how her father had rallied the prisoners on the death march, so much so he was believed to have saved several lives with his enthusiastic encouragement. Then when the prisoners were stationed at Tarmstedt in a merchant marine camp with sickness rife, McCormack had organised a still to brew alcohol to further buoy spirits.

“He had never told me this,’’ she said, “but this definitely sounds like dad”.

McCormack remained in the RAAF, and immediately after the war became director of navigation at RAAF headquarters.

Later McCormack was seconded for 12 months to the United Nations, serving in Peacekeeping force of the Dutch Indonesian independence fight, after which he was posted to the 34 Squadron at the Edinburgh base in South Australia in charge of the transport wing of the air support group for atomic weapons research at Woomera.

But he and his wife Nina experienced personal tragedy when their first born, Rory, 4, died alongside another four-year-old Adrian Dinnison in a shocking drowning accident in a deep tank on the RAAF base at Mallala in July 1953 and then a second baby boy died soon after birth. They ended up with three surviving children.

While dealing with that family tragedy and deep grief McCormack would fly equipment and the VIP’s around, including to the first atomic tests conducted on mainland Australia at Emu in October 1953. On one test occasion he stood near to the British chief scientist Sir William Penney, with their backs to the atomic blast, the archive documents show.

Michele McCormack said her father also flew scientists through the radiation cloud after one blast, so that they could dangle measuring equipment out of the plane’s windows.

“So you know they are right in the midst of that, and 85% of the people that have been there died of cancer, so yes it was a nasty, nasty time,” she said.

McCormack was awarded the highest peacetime medal the Air Force Cross in 1955, for work in assisting flood victims in Northern NSW.

But by 1957 he had left the RAAF and he took up farming just outside of Moura in Queensland. Michele said the whole family had been devastated with the loss of Rory and then the baby, and her father became a farmer in Queensland so that his two younger children could be brought up outside of the constantly moving military life and enjoy a rural lifestyle.

Several decades later, McCormack was diagnosed with cancer and he returned to Rudkoping on the island of Langeland with his family in 1996.

He was thrilled to find townsfolk had erected a sign for the “McCormack Path” near the barn and a small sign telling of his war story.

Michele said: “Like a lot of extroverts, there is very much introvert stuff for them as well. And he kept a lot to himself. Even the pain in his feet you’d see him sometimes just gasp a little bit and you realised that he had sort of gone through hell in there, but never said a word.”

For years McCormack had also sought information about his older brother Bernard McCormack, seconded to RAF squadron 129, who had been killed during the war.

McCormack learned that Bernard died on June 19, 1942 while patrolling off the Isle of Wight at 1000 feet. A pair of Focke-Wulf FW 190’s had used the thick evening sea haze to mask their approach. Bernard McCormack had been shot down by German pilot Oberleutnant Julius Meimberg on his 19th of what would be 53 aircraft scalps.

Alan McCormack died in 1998.