It’s the dead of night in the winter of January 1944, and the skies above Britain are swarming. Daring pilots of the elite Bomber Command air force – drawn from Canada, Australia and Great Britain – are bound for Berlin to stage a raid the Allies hope will bring Nazi Germany to its knees. Planes fly under darkness until they reach the German mainland, and then the sky lights up like a highway.

At 12.19am on January 29, a Lancaster heavy bomber with the serial number JB412 roared down the runway at Wyton, near the medieval township of St Ives in Cambridgeshire, to take its place in the formation flight in the skies above blacked-out Britain. The crew of seven were all Britons except for one Australian, flight sergeant John Tree. With the rest of 83 Squadron, their mission was to head for a waypoint over occupied southern Denmark and then turn for a long south-easterly leg heading for the Big City, Berlin, which was cloaked that night in thin clouds. Danish villagers’ memories of the explosions over their homes would pass down through the generations.

In the unpressurised aircraft, temperatures were as low as minus-40 degrees.

Navigators at least had the luxury of being able to plug into the electrics of the aircraft; they sometimes had wires in their uniform working like an electric blanket. The noise in the four-engine Lancaster bomber was “ear-splittingly loud”, says Dr Lachlan Grant, a senior historian at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. As planes neared the German border, flares, flak and searchlights made the sky suddenly bright as anti-aircraft guns sent up bullets from the ground and night fighters patrolled the skies.

One German plane, a Junkers Ju 88, had a highly-skilled pilot at its controls – 23-year-old Gerhard Raht. When war broke out, Raht had ignored his parents’ pleas to join their family’s furniture-making business, and had instead joined the Luftwaffe straight from school.

Raht was already a veteran of numerous air battles when he took off from his position that January night at Lütjenhorn, 20km south of the planned Allied route.

Raht would go on to claim 58 Allied aircraft, and be awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross with Oak Leaves – one of Nazi Germany’s highest military honours.

The Lancaster’s pilot, Willy Simpson, tried to corkscrew away, but at 2.20am Raht hit the plane and set it alight.

The Allied crew prepared to jump for their lives. In his position as mid upper gunner, Tree was wedged into an exposed space in the top of the fuselage – but he managed to climb down from his position and prepared to exit the burning plane.

Around them, planes were exploding and falling from the sky. Over the next hour – 66 minutes of hell to be exact – another two planes carrying young Australian airmen would go down. Some survived and were taken to Prisoner of War camps. Most did not.

The survival rate for a Bomber Command airman was devastating. That night alone, 49 planes were lost.

Tree was wearing his parachute the last time the plane’s wireless operator Bill Livesey saw him, holding the ripcord as he prepared to leap from the door near the tail. “He turned round and looked at me but never said anything, as we were in a bit of a hurry,’’ Livesey would later write, with classic understatement. “But he did not look in panic at all.’’

Livesey and rear gunner John Fell followed Tree out of the plane, and they lost sight of each other as they tumbled into the darkness.

Hans Brandt, aged 11, looked skywards from his home in the village of Skovbøl, in Nazi-occupied Denmark, and saw the searchlights from Flensburg seeking out the Allied bombers.

As the noise from the planes came closer, sirens sounded and villagers ran for a cellar that had been reinforced with iron beams (months earlier, an Allied plane under attack had released bombs that killed several cows in the nearby paddock). Years later, Hans recounted to a history website how other villagers “came into the cellar saying they had seen a burning bomber to the south east of the village, flying at a very low height”.

When daylight came, Hans, his two brothers and a school friend ventured out and found the wreckage of the Lancaster bomber, scattered over a wide area in the fields close to the village of Varnæs. The engines had fallen off one by one and were lying in a pool of oil, each in a crater of its own, with the fuselage lying on a nearby ridge in two parts. Inside the gun turret they could see a destroyed machine gun and lots of ammunition.

“The tail was lying by itself some distance from the fuselage,” Hans recalled. “It was filled with thin strips of tinfoil. We knew they were used to jam German radar. There was no trace of the crew.” Hans said he was later told the airmen had bailed out with their parachutes, but from a height that was too low, and none of the seven crew had survived. The rumour was untrue. While navigator John Martin and flight engineer Thomas McCash from Glasgow (who had only joined the crew that month) had indeed been killed on landing, four others – wireless operator Bill Livesey, bomb aimer Ronald Pilgrim, pilot Willy Simpson and rear gunner John Fell – survived.

The Australian flight sergeant, John Tree, was missing.

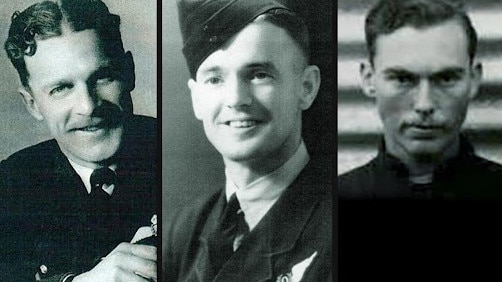

An 18-year-old sheet-metal worker from Mitchelton in Brisbane when World War II broke out, Tree had signed up as a reservist in 1941, and a year later officially joined the RAAF. After several months’ training in Australia, he boarded a ship to Canada then made his way to the UK in April 1943, where he served on attachment to the Royal Air Force.

Like many aviators from across the empire, he was assigned to Bomber Command, the bomber force put together by British military leaders who were desperate to avoid the bloodshed seen in the trenches of the Great War just two decades earlier. Tree’s diary, carefully preserved by his niece Lorelle Friden, records his movements and his observations.

He was posted to Wyton RAF base as part of 83 Squadron, and assigned to the Lancaster heavy bomber with the serial number JB412 and the call sign B for Baker. The six other men of his crew would become his best mates. He wrote home shortly after receiving his assignment, enthusiastically describing them as a “great mob of chaps”.

They are all Englishmen and all sergeants, he wrote to his parents, Rachel and Arthur, back home in Brisbane.

I have had a few trips with them on the plane and have great confidence with them all, especially the pilot who is a redhead and talks with a real Lancashire accent. The officer who gave him the test said he looked as rough as a diamond but was as firm as a rock and would make a very good pilot.

Their names are [Willy] Simpson the pilot with a mop of uncombed red hair always sticking out from under his hat. Ron Pilgrim who is tall and dark and is classed as a very good bomb aimer. John Martin the Navigator who is always running late but always manages to get the correct course to get us back home. Bill Livesey the Wireless Operator is a little chap with a partly bald head of fair hair and a funny little giggle, we call him Willie the Wop.

Then there is Cliff Reid, the Rear Gunner who is 19 and he is the one from Wales. (Reid’s usual spot would be taken by John Fell on the flight that was shot down over Denmark). So now you have it all and they really are a great mob. Of course I am the Mid Upper Gunner.

On days off, Tree went to the pictures, or to see the sights, visiting Windsor Castle and Ascot races, where he marvelled at the Eton College boys in their top hats.

It was a strange life, with his days off spent wondering when the next mission would come, and if he would make it home for breakfast of bacon and eggs. This was a real treat in heavily-rationed England, and well-earned by the men fighting in the most dangerous theatre of World War II – the skies above Europe.

British prime minister Winston Churchill had earlier halted the bombing campaign on Berlin for several months due to the unacceptably high number of Allied planes that were being lost. But the development of a Mark III version of the radar system known as H2S or “Home Sweet Home”, which enabled German targets to be identified at night and in all weathers, made the prime minister think again. Tree’s plane, Lancaster JB412, was one of only six test planes that had this advanced radar.

Tree’s diary shows a matter-of-fact approach to the dangers of his job. “Tonight we raided Leipzig got hit with flak over target then got shot up by night fighter over coast,’’ he wrote after a particularly difficult mission on October 20, 1943. “Made crash landing at Newmarket with one wheel flat, no flaps, bomb doors open, no brakes. 3 engines.’’

No brakes, no worries.

Airmen in Bomber Command were required to fly 30 missions but Pathfinders – elite aviators who had the unenviable job of leading the way and marking the target with flares – were required to fly 45 missions, significantly upping their chances of becoming a casualty of war. Those who weren’t killed on raids often died in accidents, or were taken prisoner of war. The Imperial War Museum in London says only 24 per cent of those in Bomber Command were unharmed by the end of the war.

The Pathfinders attracted significant heat from Nachtjagdgeschwader 3 – the group of German night fighters based close to the German-Danish border. The night fighters considered these missions Himmelfahrtskommando or “a trip to heaven” and fought like they had nothing to lose.

The Pathfinders were led by the brilliant Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett, an Australian from Toowoomba, who is rated by some as the country’s most unheralded war-time leader.

John Tree was a Pathfinder.

At 2.26am, six minutes after Tree’s plane was hit from behind by the Junkers piloted by Gerhard Raht, a nearby plane from 463 Squadron RAAF – a Lancaster with the serial number HK537 – was also in trouble. West Australian Norman Percival Cooper, an experienced pilot, had already turned the plane around and was heading back to base with engine problems.

The two other Aussies on board Lancaster HK537 were Perth man Lewis Havelock Christmass, 26, the bomb aimer - a most important job given the 4000-pound (1800kg) blockbuster bomb they were carrying - and George Jeffreys Kerr, a school teacher from Springvale in Victoria, who was the navigator. A Canadian and three Brits rounded out the seven-man crew.

All on board were killed when a plane broke up above them and they were hit. They crashed in a huge ball of fire in a pig farmer’s fields on the Danish island of Als. Eyewitness Sigurd Sørensen, now 86, described how the windows of the family farmhouse were blown out from the pressure of the explosion as HK537 came down. “My heart was pounding,’’ he told The Weekend Australian Magazine.

Sørensen’s parents would later bury a body they found in the field, a young man’s whose mortal remains were overlooked when the Germans came by to gather up the dead.

His father engraved a propeller with the words: “ An English airman here rests with honour far from his home and his loved ones. 29 January 1944.” His mother Kate planted a tree over the grave to give it shade, but German supporters heard of the family’s Allied sympathies and poisoned the tree.

It appeared to die, until a few months later, when three small saplings emerged, undefeated, from the trunk.

“We didn’t know who he was, although a dog tag had been found in the wreckage [in the name of] Francis C.W Bull and so that’s what we referred to him as,’’ Sørensen said.

After the war the family organised a proper burial with a priest for the airman, but a year later English officials exhumed the body and buried it with the rest of the crew in the military section of the local cemetery in Aabranaa.

“My father was never convinced that the airman was Bull because the dog tag wasn’t on him,” Sørensen recalled. “It was just in the field along with all the bits and pieces of the plane. We thought everyone on the plane were Englanders. Only later we learned there were Australians.” The identity of the airman was never fully confirmed

Every Saturday, Sørensen and his family undertake a small ritual in the field where the airman died. They hold a short service and lay fresh flowers near the propeller.

They are still finding bits of wreckage 80 years on. He pulled out a bag filled with mangled metal. “This is from the last year,” he said.

Unlike the Lancasters JB412 and HK537, the Halifax bomber with the serial number HK294, piloted by young Queensland real estate agent Alan McCormack, reached its target in Berlin. It dropped its bomb load: two 1000-pounders and two 500-pound bombs, as well as some cluster bombs. But disaster struck in German skies as the plane turned for home and was hit by flak from below.

“We were hit in the belly while the bomb doors were open,” McCormack later recounted.

At 3.26am, the Halifax went down. Six of the plane’s crew survived – the sole casualty was a natural sportsman and experienced swimmer named Jack Tylor, from Katanning in Western Australia, who would die after landing in water.

McCormack became a prisoner of war in the Stalag Luft III camp in Sagan, where his senior rank ensured he quickly met Roger Bushell, the architect of the Great Escape plans, made famous by the Steve McQueen film of the same name. The prisoners, all airmen, dug three tunnels in porous sandy soils, going down more than eight metres before making headway under the prison perimeter more than 100m away in an effort to get 200 men out.

The plans were well advanced when McCormack came into the camp in early February 1944. He said he joined the escape committee but didn’t take part because he hadn’t contributed to the extent others had for many months. However, McCormack’s secretly hidden supplies – a silk map, two button compasses and a comb with hidden needles – did make it out of the camp with one of the 76 who escaped. Nearly all were rounded up in the following weeks in a massive manhunt, and 50 would be brutally executed on the orders of a furious Hitler.

McCormack would survive through months of the perilous death marches, and was liberated after the war ended in 1945. He would end up back in Australia flying VIPs through atomic tests at Maralinga.

In the days after Lancaster JB412 went down, a cable was sent to John Tree’s parents, Arthur and Rachel, advising them the plane had failed to return from a mission and their son was officially missing.

Wireless officer Bill Livesey landed safely on farmland in Blans, where he spent several hours wandering before he approached a large farmhouse, Ballegård, and knocked on the front door. Rear gunner John Fell also landed in ploughed fields and sought help from farmers in Rufas, near Ullerup. Livesey and Fell were both taken as prisoners-of-war.

Ron Pilgrim, the bomb aimer who had gone out the front escape hatch, landed in a rhododendron bush in the backyard of the local vicarage a kilometre to the north.

The current vicar, Lis-Ann Rahm, told The Weekend Australian Magazine she believed the airman then sought refuge in the barn, and while the clergy of the district wanted to look after him, police instead alerted the German occupiers. “The pastors were trying to decide what to do, but in the end the decision was taken away from them when the Germans arrived,’’ she said.

Willy Simpson, the pilot, who had been last to leave the plane, landed on the roof of a telephone exchange, injuring his head.

He tried to negotiate with the locals, who spoke no English, and by 9.20am the Germans arrived and transferred him to Dulag Luft, near Frankfurt, for interrogation. Like the others rounded up, Simpson would be held there for around two weeks before being allocated to a prisoner of war camp.

For nearly 18 months, Tree’s parents held out hope the second oldest of their four children would be found alive.

But in July 1945, Livesey’s sister Alice Yates sent a letter to Tree’s sister Annie Gagliardi in Brisbane. In it, she thanked Annie for a cake sent across the seas to the UK, indicating a warm relationship between the two families, before moving on to sobering news.

“Well Ann, I told you Bill had written to the Red Cross about Johnnie, today he got a reply,’’ the letter states. “I said I would let you know Ann if we got to know anything. Well, I am going to keep that promise, although it is not pleasant news I have. I am going to put the message word for word as we received it Ann I think it will be better that way.

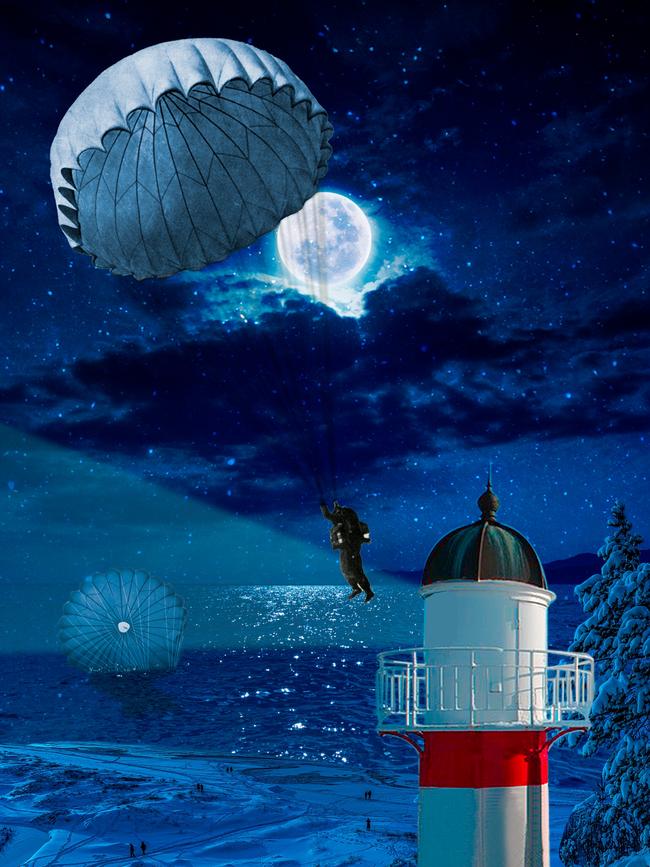

“Here it is: The RAF & Dominions Missing Research & Enquiry Service have discovered that the body of F/S [Flight Sergeant John] Tree was washed ashore on the 19th of June 1944, near Ballebro Lighthouse, Avnbol, and was buried on the 22nd of June 1944, in grave no. 23 in the Cemetery at Aabenraa, Denmark.”

She then added: “Well, Ann, there is nothing I can say about that statement. We can only pray for you all. I can’t write any more now Ann, so Goodnight and God Bless You All.”

It was a crushing blow for Arthur and Rachel, and the three surviving children – oldest sister Annie, younger sister Hazel, and Arthur.

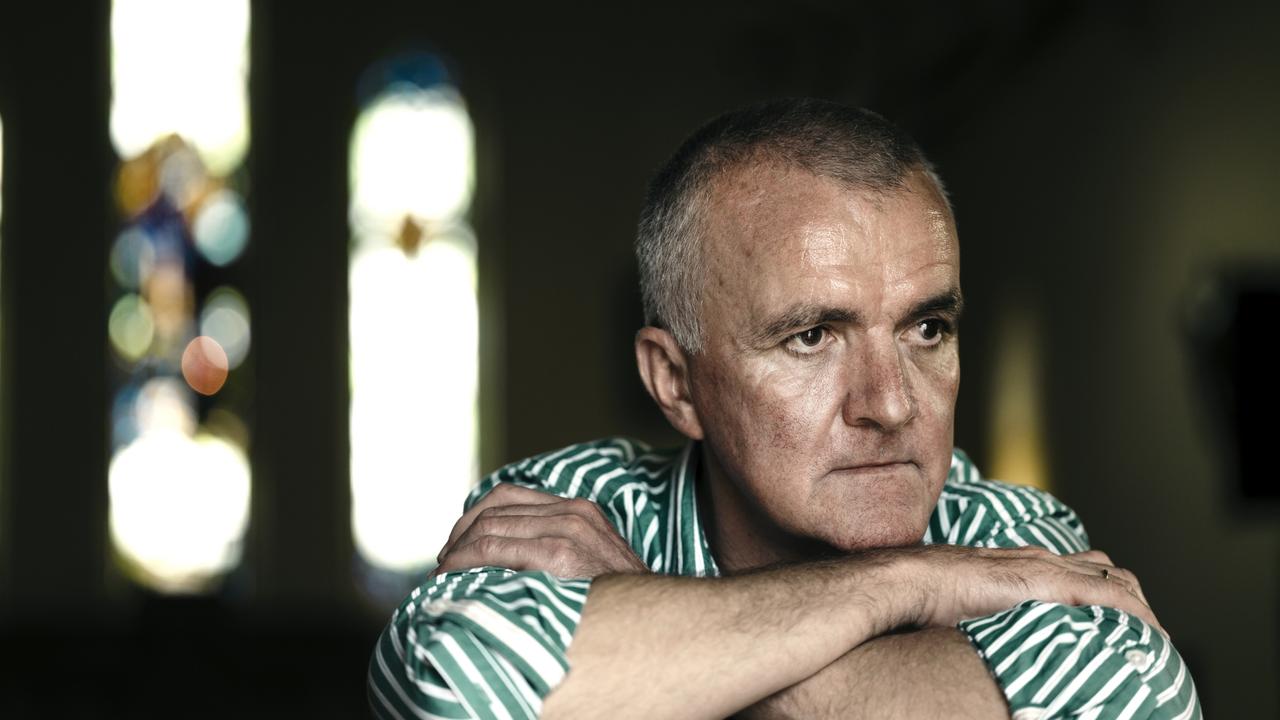

“Up until then the family had kept hope above hope that with no body, he might still be alive,’’ said Tree’s nephew, Federal Circuit and Family Court Judge Peter Tree. “But that came crashing down when the body came up and the Red Cross figured out who it was.’

Justice Tree’s father was Arthur, the youngest son, who wasn’t even in his teens when his beloved brother John was killed.

“It’s all pretty grim,’’ Justice Tree tells The Weekend Australian Magazine of his uncle’s final minutes. “As I understand it, he exited the plane successfully, parachuted successfully, but had the bad luck to fall into the North Sea.

“Middle of winter ...

-

“The reality is he wouldn’t have lasted more than 10 or 15 minutes before hypothermia would have killed him.

-

“It must have been foggy I assume and the Danes that were pro-Allied would have been worried about their own safety if they’re looking for and finding Allied airmen.’’

John Tree landed in the sea off the Danish island of Als. His niece Lorelle Friden travelled to Denmark from her home in the US decades later, and spoke to Danes who remembered fishermen saying they’d heard someone calling out for help into the foggy darkness.

“But they couldn’t find him, they couldn’t get a direction towards his voice,’’ Justice Tree said.

Alone in the darkness, he died.

In June 1944, Tree’s body washed up ashore near the Ballebro lighthouse. The Red Cross and Australian and British war offices had continued to make inquiries about him. The Danes collected his body, and buried him in a local cemetery.

Devastated to learn of their son’s death, Arthur and Rachel placed the photograph of John in his RAAF uniform, his forage cap sporting the white flash insert which indicated he was a volunteer in training, above the kitchen table in their dining room.

“It’s difficult to actually explain the full impact on his family. I would put it as catastrophic,’’ Justice Tree explains. “I don’t think they ever really dealt with it in a healthy way. I never had a conversation with my father about his dead brother, and I think that’s because my father couldn’t bring himself to speak about it.’’

The family donated some lights to the church on the hill close to their home where the Trees had worshipped for generations, St Matthews Anglican Church at Grovely. The Art Deco-style pendant lights hang to this day in front of the roll of honour – which includes John Tree’s namesake uncle, John Robert Tree, who’d given his life in the Great War years earlier.

In 2018, reading the eulogy at his father Arthur’s funeral, Justice Tree referenced a letter written by Arthur in response to a book detailing John Tree’s life, written by the unofficial family historian, Lorelle Friden.

“It brought a lot of memories back, and to be honest, I spent most of the morning crying,’’ Arthur wrote. “As a child I think my grief was overlooked. Adults had important grief but what was mine? Actually, I was already plotting my revenge but the war ended, and there were no enemies left.’’

John Tree was the silent guest at every family gathering, looking on from that sepia-toned photograph on the wall of his parents’ Queensland home, so deeply mourned his name was never uttered aloud.

Today, 80 years after Tree’s death, the role that Australians played in Bomber Command in World War II remains largely overlooked compared with the fame and glory attached to other military campaigns - although a major new exhibition at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra in 2025 will go some wat to redressing that imbalance. Around 4100 Australians were killed serving in Bomber Command in World War II; the War Memorial notes that more than one in three members of the RAAF who served in Bomber Command were killed.

While Bomber Command’s more lauded exploits include the “bouncing bomb” Dambusters raid of May 1943, the force’s participation in the devastating attack on the city of Dresden in February 1945 cast a stain on its reputation. A memorial was not erected until 2005 in Canberra, while in London, it took until 2012 for authorities to build a dedicated monument to their sacrifice.

Of more than 400 Allied planes shot down over Denmark, 82 were crewed in part by Australians. A total of 146 known Australian servicemen lie in Danish cemeteries, their legacy kept alive by Danes who never forgot their sacrifice.

The people of Denmark, neutral in the war but occupied by Germany, have since the 1940s honoured the sacrifice of the foreign airmen who fell onto their islands and farms, and will mark the 80 years since their deaths with a permanent memorial and a commemoration.

Danish historian Anders Baadsgaard Straarup says local villagers had formed many small associations to erect and look after 74 memorial stones across the country.

“One day normal people take care of their daily lives and suddenly an aircraft comes down and they have the war on their doorstep.

-

“They had to do something, they could do that in a number of ways, [which included ensuring that the airmen] had a decent funeral... another was to remember them.”

“We have our history, the crew of this bomber is also part of this history.”

In Denmark, officials have arranged a commemoration service on January 29 at the memorial stones for Lancaster HK537, as the loss of so many Allied lives still resonates deeply. Later in the year the community is planning to unveil a sculpture representing the airmen who crashed throughout all of the war, amd to host an exhibition with all relatives - as well as Denmark’s newly-crowned Australian-born Queen Mary - invited.

Lorelle Friden and Justice Peter Tree are now trying to find the families of those who flew with their uncle, and introduce them to the Danes who have honoured his memory for eight decades.

Says Justice Tree: “They have very much taken the flight crews to heart because they were a physical manifestation of defiance to the Germans. I actually find it hard to believe that for a country that had no real connection to these people – other than they got shot down over their country – they’ve taken them to heart. And they have, these are important people to the Danes. They’ve built over the years some really low key and very respectful memorials to the aircrews and each year they conduct commemorative services there.

“The irony is of course that there’s no family members of the airmen there and their lives are strangely being celebrated by people who never knew them and have no real blood connection with them. It would be great if we could get a family representative of each of the crew members at the opening of the memorial.”

Bill Purdy was a pilot with 463 Squadron RAAF, operating out of RAF base Waddington in Lincolnshire, one of the 10,000 Australians who served in Bomber Command. Now 100 years young and spending his time golfing and playing bowls in suburban Sydney, he vividly recalled that the worst times of each mission were when the aircraft were still on the ground, shortly before they took to the skies and headed out over Denmark into German territory.

“The hardest part always was when you found out in the morning that you were going to operate that night. Then you went out and tested your aircraft and made sure everything was working,’’ he recalled.

“Then you had a briefing round about dusk and then you found out where you were going.

“And that couple of hours between finding out where you were operating that night and getting into the aircraft was about the hardest I could ever remember.

“You went back to your room and packed everything up so that it wouldn’t be too much trouble to send it back to Mum.

“Write the last letter and that was that.’’

British Bomber Command veteran Dick Raymond’s last thought was always the same, as he lifted his boot off the tarmac and onto the ladder into his plane. Would it be the last time he set foot on English soil?

“On every operation I had that very thought as I got in the plane,’’ 99-year-old Raymond, a Pathfinder flight engineer, recalled to The Weekend Australian Magazine from his home in North Wales. “All I can say to anyone who asks what it was like, I can only tell you that you had to be there.’’

John Tree, too, packed his belongings before he climbed for the last time into his usual place inside the Lancaster’s mid upper gunner turret on what would be his 28th and final sortie.

His personal items, including a few letters and postcards, would eventually be sent home in a box to his family in Brisbane. Lorelle Friden and Peter Tree have carefully stored his belongings, and his other letters home.

On December 24, 1943, their uncle wrote to his family in Brisbane.

“Well here it is, Christmas Eve once again, or as I work it out, it has just turned Christmas Day in Australia,’’ he wrote.

“So to let you see I haven’t forgotten you all, I will say a merry Christmas to everyone at home and a very happy new year.

“I’m sure we will be together again by next Christmas.

“Lots of love and kisses, John.’’

POST SCRIPT: The 4100 Australians who made the ultimate sacrifice in the skies above Europe will be recognised in a major new exhibition at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra in 2025.

Words | Jacquelin Magnay, Ellen Whinnett

Art Direction & Design | Sean Callinan, Idit Nilsson

Animations | Steven Grice, Helen Simmons, Sean Callinan, Andrew Belousoff

Production | Fay Gould, Jessica Clement

Development | Priyanka Jacob

The Weekend Australian Magazine | Jessica Clement, Clarissa Cavalheiro, Ross Bilton

Audience Strategy | Elyse Popplewell

Commissioning Editor | Elizabeth Colman

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout