Voyage to Arctic Norway aboard Ponant’s Le Commandant Charcot

Contrasting with the epic and inhospitable frozen landscape are a blizzard of swish luxury amenities aboard Ponant’s innovative icebreaker.

The bear pauses on the ice, turns to face us and sniffs the air. A hush falls over the crowd gathered on deck. Satisfied, she ambles over the ice floe. Shutters start rapid-fire clicking, while binoculars are focused with urgency. Then a gasp goes up. From behind a block of blue-white ice, two cubs appear, scampering in their effort to keep up with Mum. She seems on a mission, plunging into the jet-black water between two ice floes. Another collective intake of breath as both cubs scramble onto her back, hitching a ride. The little family clambers onto a chunk of ice, shaking off the water, and wanders off into the never-ending whiteness.

Such exhilarating sightings are typical on Le Commandant Charcot, the last word in icebreaker chic. Launched by French-owned Ponant last year, the vessel is expressly designed for polar expeditions, able to bash further and deeper into pack ice than any other expedition ship thanks to a reinforced hull. It runs on hybrid power generated by relatively sustainable liquefied natural gas and battery packs and is smooth, sleek and virtually silent.

–

Discover epic adventures from Africa to the Arctic in the latest edition of Travel + Luxury magazine.

–

Elements of the ship, including a fleet of Zodiacs and a helicopter that flies ahead of us to scout the ice, are all business. Below decks a pair of working science labs is where up to four academics per voyage are invited to study anything from microplastics to climate change. The guest areas, meanwhile, are a symphony of cream, stone, fawn and sea blue, with interiors by renowned architects Jean-Philippe Nuel and Jean-Michel Wilmotte. Cocktails flow from mid-morning onwards in the serene Observatory Lounge where you can recline in a polished sofa with a Martini and gaze out at the snowy terrain. Upscale Nuna restaurant is the first at sea from superstar French chef Alain Ducasse.

My journey begins in Spitsbergen, an island in the remote Svalbard archipelago, some 800 kilometres beyond the North Cape of Norway and 1050 from the North Pole. Jagged black mountains surround the bay of Longyearbyen, from where ships depart. Splotches of white on the peaks are reminiscent of the markings of the orcas that sometimes cruise these cold waters. There are no trees, and low-rise buildings huddle against a wind-whipped shore. It’s peak season in June, and four or five other expedition ships are ferrying passengers back and forth to board. But these ships will stay around Spitsbergen island, its coast frilled with fjords and glaciers.

Our destination is Nordaustlandet, the ice-draped wilderness to the north-east, and thrillingly, beyond into the seemingly infinite pack ice. Our first stop is Ytre Norskøya, a speck of an island that in the 17th century was a Dutch whaling station – a miserable place to spend either summer or winter, although the whalers attempted both. Here, we learn the expedition team’s definition of an “easy” hike, something that’s to become a standing joke throughout the trip. I’m kitted out in my smart new Ponant expedition parka, which is mine to keep, and “mud boots” issued by the ship – essential since you’re often clambering off a Zodiac into calf-deep icy water.

I struggle up a bank of large pebbles and sink immediately and unexpectedly into a bog. We traipse along a long, marshy shoreline, monochrome apart from the rust-red tint of pebbles, and struggle, panting, up a steep, snowy ridge. A handful of ancient graves on the rocky shore, marked only by planks of bleached wood, are the final resting place of some of the Dutch whalers. The coffins have been pushed upwards by the permafrost and in one a skull is still visible, which, inexplicably, makes me shiver. Most of the whalers, one of the guides explains, died of scurvy rather than animal attacks.

Back on board, I ease my aching muscles in the indoor pool. The ship has an inviting spa with a glass-walled sauna and, bizarrely, a snow cave, which seems incongruous when all we can see outside is snow and ice, but I sit in it nonetheless. Evenings on board range from expedition casual – fleeces and jeans – to two nights when it’s formal attire, with some even trotting out black tie and sparkly dresses. I settle for palazzo pants and a floaty top, which fit in just fine. It’s as though there are two worlds here: the freezing one outside, and the cocoon of luxury inside, marked by the soft sigh of Veuve Clicquot magnums being opened and Kristal caviar on the menu.

Captain Patrick Marchesseau, who’s endlessly enthusiastic whatever the hour, wakes us at 7am with an announcement that the sky is blue, the weather a balmy three degrees and a chance has presented itself for an “advanced” hike. It’s made pretty clear this is hardcore mountaineering and only the fearless need apply. I opt for a more modest excursion that involves a killer ascent of a glacial moraine dotted with patches of bright-purple saxifrage. Three Svalbard reindeer, whose long, shaggy coats and stumpy legs set them apart from their mainland cousins, graze near our landing spot. Later, as the patches of ice in the water knit closer together, we spot seals hauled out onto the pack ice. A fishy smell leads us to a bachelor herd of walrus, their tusks a metre long, lying fatly on the shore, grunting and squabbling with one another.

While the hikes are tough, life on board is indulgent. We return from outings to smiling crew members offering hot chocolate with rum shots, or gløgg (mulled wine). One evening, I emerge from a lecture in the theatre and a caviar display has been set up, passengers descending on it like ravenous gulls. Another day, it’s dainty macarons in a rainbow of pastel colours. At lunchtimes, the outdoor barbecue by the Inneq Bar on deck does a roaring trade in grilled lobsters. In the evenings, there’s fresh sushi and a splendid buffet in the Sila restaurant, high up on deck nine, which I love for the endless frosty vistas from the floor-to-ceiling windows. Most people, though, head to chic Nuna restaurant, to enjoy the wares of chef Ducasse, tucking into truffled guinea fowl, sea bass with sea-urchin butter toast, organic snails in garlic butter, and beef carpaccio with confit tomatoes.

I love the detail and passion that goes into the food. For lunch and dinner, there’s a spectacular array of cheeses from Brittany-based Jean-Yves Bordier, official supplier to the ship. Every little pat of salted butter is individually hand-wrapped. A chocolate mousse comes in the shape of a miniature Le Commandant Charcot. The ship has an open bar, the wines poured at dinner including an excellent Pays d’Oc rosé and a fine syrah from Pays d’Hérault. Some choose to upgrade to the premium wine list, where a 2017 Puligny-Montrachet costs €95 and a 2015 Saint-Émilion Grand Cru €60.

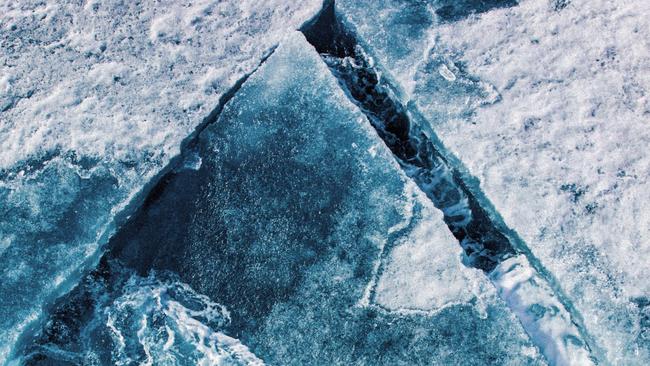

I wake on the fourth day to a relentless booming noise. “Are you ready for some ice?” asks a jubilant Captain Marchesseau over the ship’s PA. “This is just an amuse-bouche.” I quickly realise that the booms are our bow hitting blocks of ice. Cracks rip through each vast plaque as Le Commandant Charcot glides forward, shattering as chunks separate off. In Svalbard, ships aren’t allowed to break the fast ice, which is attached to the land, but all around us, the sea is frozen, and the ship is in its element. The announcement goes out: a polar bear has been spotted. Everybody rushes on deck. The bear is admittedly a cream-colored speck in the distance, but the thrill is undeniable. Shortly after, another bear swims at speed between two drifts of ice across the glass-still water, leaving a perfect triangular wake behind it. I find it extraordinary that these enormous mammals are so perfectly adapted to this extreme environment, and heartbreaking that their world is shrinking.

All around us now the world is white. Nordaustlandet is draped in Europe’s largest ice cap, called Austfonna, a vast dome, smooth like a wedding cake. The ice meets the sea in the towering, blue-white cliffs of a glacier face, an unimaginable 180 kilometres long, shot with streaks of sapphire. Waterfalls cascade out of the ice and every now and then there’s an ear-splitting crack, followed by a rumble and a small tsunami as chunks of ice calve into the black water.

I head out on a Zodiac with Marilia Olio, one of the naturalists on board. There isn’t much wildlife around, but Olio, who studies whales, drops a hydrophone into the water. To my astonishment, a whole new world springs into life, with the haunting echo of a high-pitched song. “That’s a blue whale,” she says, excitedly. “It could be anywhere within 10 kilometres.” Next, an unearthly, trilling whistle blasts out. We all jump. “A bearded seal,” Olio says, laughing. “It must be nearby.” This landscape of sound is almost more exotic to me than the icy world that transfixes me day and night.

Land, such as it was, is far behind us now, and the ice and the relentlessly bright, white sky merge into one. The ice is almost solid this far north, up to a metre thick, rounds welded together, some with tumbled blue blocks on top where patches have collided and buckled. The sea is jet black. The ship judders as it hits the deeper blocks, sometimes flipping them over to reveal undersides of shimmering aquamarine. Watching the ice fragment is utterly hypnotic. Everybody has been lulled into a dreamlike state. The call comes from the bridge that a bear has been spotted with a fresh kill – and the excitement mounts as a second bear comes into view. Both animals have faces scarlet with the seal’s blood. The larger individual is lying down on the ice, feeding with its back legs splayed like a frog. The younger bear is curious – it prowls from one ice floe to another, constantly sniffing the air, watching us, motionless in the ice.

I feel a real sense of loss as Captain Marchesseau sets a course south 24 hours later. Very quickly, the sawtooth mountains of northern Svalbard form a spiky line on the horizon. On the last day, I hike up to a viewpoint in Tinayrebukta in the Northwest Spitsbergen National Park, photographing tiny Arctic flowers in pink, green and yellow. I wander along the beach observed lazily by a trio of ringed seals basking on a rock like the Three Muses, puffins skimming past me and landing on the water. Life seems so lush and abundant here after the icy beauty of the polar sea, which is absurd, as I’m still in one of the most inhospitable places on Earth. But I’ll never forget that sense, and privilege, of being suspended between ice and sky, completely alone in such a fragile, devastatingly beautiful world.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout