For 10 years, Sandra Crow has shielded her husband Trevor — a former rugby league club chairman and gifted second rower — from the outside world. Now she’s lifting the veil on what the ugly, violent end of a brutal career looks like.

It takes two of them, Sandra and the carer, to wrestle her husband Trevor Crow into the shower, pinning his hands while she swabs him down quickly, fearful of the violent blows and abuse likely to come.

The home where the former Newcastle Rugby League chairman, once a St George second rower, is now staying offers one-on-one care. But sometimes even that is not enough.

Trevor is non-verbal, physically destructive, often bed-ridden, barely able to feed himself and wears an adult nappy. He is 63 years old.

Trevor’s medical team says he is succumbing to dementia induced by the repetitive head knocks he suffered while playing the game from age five to 36.

In moments of despair, Sandra has seriously thought about ending Trevor’s life and her own. These thoughts creep into Sandra’s head not only because of the violent, frightening episodes when her husband lashes out, but also because she realises there is almost nowhere safe for the man she still loves to live out his final days.

“We still have a great love,” Sandra says.

“I’m just not getting it from him anymore.”

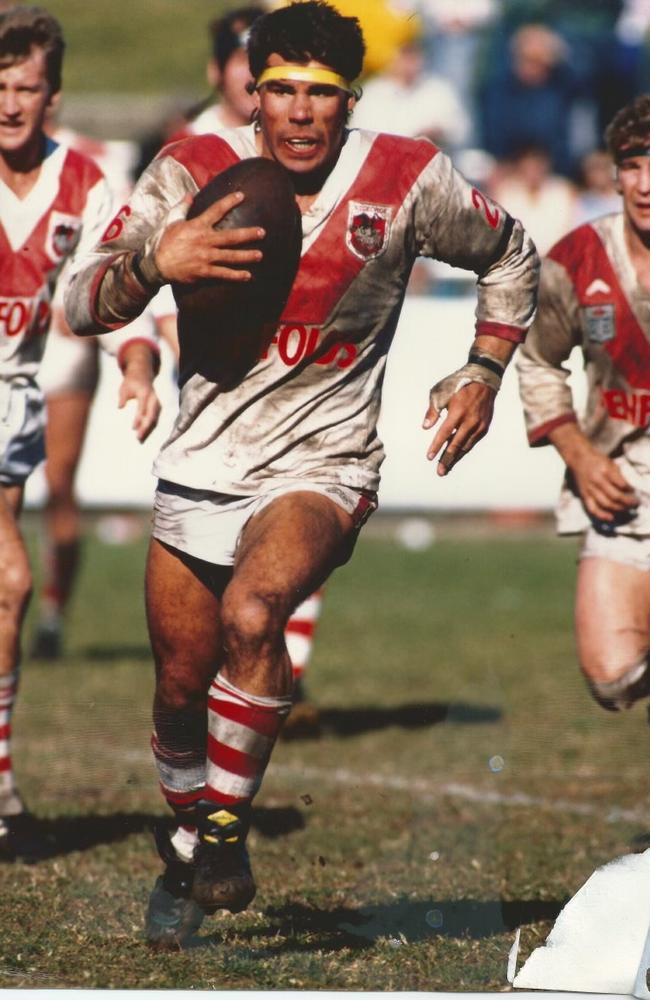

This Trevor is not the man she married, who helped to raise their two children. He is no longer the man who once played at the highest level of rugby league as a second rower for St George in the 1980s.

Sandra is exhausted from 10 years of caring for her husband and shielding him from the outside world. A breakdown in recent weeks has prompted her to lift the veil on the unbearable reality of living with a dementia-affected former footballer in serious decline.

As his wife, Sandra tends to his most personal needs while dodging flailing arms as he violently lashes out. She tries to block out the few words Trevor still remembers: “Get f..ked. You hate me.”

Now he no longer recognises his wife.

“To just take Trevor’s and my life, just to end it … the pain would be over, because this pain is just unbearable,” Sandra tells The Australian.

“It’s just so tiring. It’s too much. It’s way too much for anybody to be able to manage this disease.”

The past few months have been a nightmare saga of trying to get appropriate help, even with an NDIS package for assistance.

Trevor has been shunted from respite care, to hospital, to care accommodation.

He is in the end stage of what his healthcare team believes is Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy dementia.

CTE can only be confirmed after death, but Trevor’s clinicians have little doubt his devastating brain condition is caused by the repeated concussive blows to his head from a lifetime with the game, which included three years contracted to St George in the late 1980s, where he played 11 first-grade games.

‘The brain does not discriminate between 1000 first-grade tackles and 1000 sustained in the second grade.’

Sandra first noticed a problem in 2015 when her easy-going husband, who had been a natural leader and had captained the Country side in the game’s annual representative fixture against City, became so much more quick to anger.

There were arguments at work and anger at home and Trevor secretly sought the help of a psychologist. Sandra only later discovered in paperwork that Trevor was already feeling depressed and suicidal.

For a decade Sandra cared for Trevor in a loving home in the suburbs of Newcastle with the help of her adult son Jordan. More recently they had the assistance of an NDIS care team.

Safety tipping point

Last year Trevor was deemed too unsafe to remain at home with Sandra. And in the past month he has been punted from care home to hospital, where he spent almost two weeks, and still there is nowhere safe and permanent for him to live out his final days.

There are no words, she says, to describe how shocking it is to live with someone with a football-induced brain injury.

“It’s just an avalanche of traumatic disturbances every day, all day,” she says. “Every day for the past few years, all he can say to me is, ‘Get effed. You hate me’. And that happens from the millisecond he wakes up until he goes to bed at night. So all day is just constant domestic violence, verbal abuse, physical abuse – you know, trying to keep his hygiene intact and care for him is impossible.”

Last year Trevor’s decline reached a new low when he no longer recognised Sandra or Jordan. His care team determined it was no longer safe for any of them to be in the home with Trevor’s increasing volatility.

“I’ve always wanted to look after Trevor forever,” Sandra says. “I always wanted him to stay at home, but unfortunately, due to his severe psychological behaviours that are linked to his CTE dementia, it means we are incapable of looking after him at home. The trauma attached to that is, it’s just unspeakable … recently, my son and I have had a bit of an emotional breakdown.

“Trevor’s behaviours are highly escalated. He’s highly aggressive, verbally violent, and it’s become quite difficult to care for him.”

A month ago the family decided to put Trevor into aged care respite for a break. It didn’t go well. Within an hour of Trevor’s arrival, he had absconded, and police were called to find him. Trevor was returned to the home, only to go missing again.

“So as far as we were concerned, he was wandering the streets, not knowing where he was going,” she says. “Was he dead? We didn’t know. They eventually found him in the facility because the police requested that they look at footage as to which direction he’d left the building … He’d actually stayed in the building.

“The poor guy was caught in a toilet and had been standing there for three hours because he didn’t know how to get out.”

In the weeks he was in temporary aged care, Sandra was briefed with 22 pages of “incident reports” of Trevor wandering the corridors, screaming, swearing and lashing out at other residents.

There was little respite for Sandra, who was back and forth to the care home most days.

“It just screams the fact that you know aged-care facilities aren’t able to look after my husband,” she says. “He’s not even old enough to be in an aged-care facility. He’s only 63 but you know they couldn’t look after him.”

Behaviour overload

Two weeks into the planned three-week stay, Trevor’s behaviour became too much for the care home, and they called for an ambulance to transfer him to hospital. Soon after he got there, Sandra was called to come and collect him.

“So when I contacted the hospital, they were saying that Trevor was compliant to be cared for and that he could be taken home,” she said. “They’d done their delirium screening. His bloods were clear. He didn’t have a UTI, and that he was okay to go home.”

Sandra checked with her health care team who told her that under no circumstance should she bring Trevor home.

Trevor’s occupational therapist, Nikki Cousins, was at that time waiting on NDIS approval for Trevor’s permanent new home.

“We submitted to the NDIS last year to say there had been a change in his situation, and that Sandra was no longer able to care for him at home any more, and his health professional team and support team all submitted reports saying that he needed one-on-one care in the community,” Cousins says.

Adhering to the advice, Sandra rushed to the hospital not to collect Trevor, but to help in whatever way she could. She found her husband in the foetal position, “heavily sedated and comatose”.

“For the hour and three quarters I sat with him and held his hand, he never moved,” she says. “I tried to talk to him; I got no response. I lifted the blanket and sheets up. He was in the same shirt I put him in two days ago. He had a nappy on. He didn’t have shorts on. He had nothing on his feet. He was cold. It was disgraceful.”

For three days Trevor was supervised in a bed at the nurses station until a single room could be found for him. During that time his personal hygiene could not be properly managed.

Sandra was visiting the hospital daily and requested he be showered. She and a female nurse were able to coax Trevor into the bathroom. “I went in and the nurse and I showered him because he had faeces all over him,” she says. “I was brutally attacked. The nurse was brutally attacked. We were verbally abused. She pressed her duress button. I was hit several times. He is non-compliant to be cared for, yet the hospital system wants to send him home.”

The NDIS option

While Trevor was in hospital, the NDIS responded to his care-team’s application with approval – not for one-on-one community care, but for community care shared with three patients and one carer.

Trevor was to join two other early onset dementia patients, a man and a woman, in a home in the community, with one carer to assist with their independent living. On visiting the location Sandra was immediately concerned and told the facility so. Trevor’s invitation to the group home was withdrawn by mutual agreement.

Cousins is blunt about what she thought would happen if Trevor had been admitted to the group home. “I expect that within a day, an ambulance will be called and Trevor will be escorted back to hospital, and someone will get very, very injured and be that one of those other two residents with the younger onset dementia, or a staff member there,” she says.

“They (NDIS carers at the home) don’t have the skills to deal with the high level of physical aggression that Trevor displays.”

Trevor’s case is not isolated. “We’re finding it quite often that when we do put in these reports to say that a person requires an increased level of funding, that they come back with this stock standard one to three,” Cousins says.

“And the reason for that is that the people who are making these determinations at the agency are not clinicians, so they’re reading on paper things that they don’t understand, and the focus is on saving money.”

Critical despair

By this stage, Sandra’s despair was overwhelming. “I didn’t know where to turn or what to do,” she says. “The hospital wanted to send him home. They thought that it was okay for him to either come back here or to go into the shared facility. I just didn’t know where to turn.”

That was a day she came close to ending both their lives.

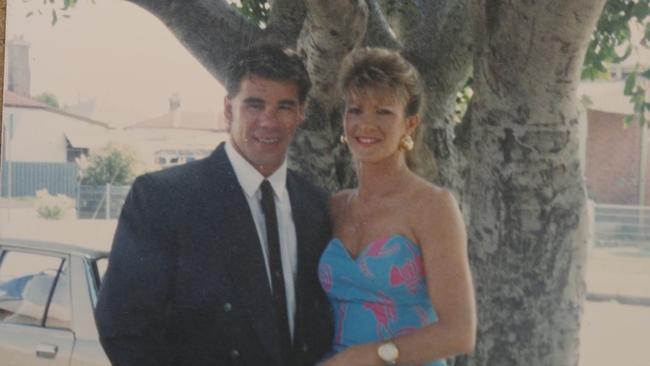

It’s an understatement to say that Sandra misses the Trevor of old. “We met when I was 13 and have been together ever since… and this year’s our 46th year together,” she says. “So we’ve been best mates for a long time … I can’t walk away. We had such a great … we still have a great love. I’m just not getting it from him any more.

“You grieve that love loss, the future, the plans you know … you get jealous and envious of your friends that are living their wonderful lives with their husbands and children, and get to go out and get to enjoy things and travel, and you can’t do that. You’re alone. It’s a very lonely, lonely existence.”

Expert diagnosis

Associate Professor Rowena Mobbs from the Queensland Brain Institute, University of Queensland, has clinically documented Trevor’s decline for the past few years.

“Trevor Crow is a true champion of the game with over 30 years exposure to head injury mainly in youth, reserve or country rugby league, and the brain does not discriminate between 1000 first-grade tackles and 1000 sustained in the second grade,” Mobbs says.

“His wife, Sandra, is a champion too for enduring this cruel and exhausting disease. It’s a marathon, dementia. We have struggled to control Trevor’s agitation and rage, making it difficult to obtain timely specialist dementia care and all at his young age of 63.”

Mobbs says dementia will soon be the leading cause of death for Australians and planning is needed now to prevent or care for all dementia subtypes.

Let down by all

There are many ways Sandra feels let down over trying to care for her husband during the past decade, not only by the health system and the NDIS, but also by the game Trevor loved.

“I think it’s important that the NRL acknowledge who they are and the job that they did to make the game what it is today,” she says. “Because without our husbands and our partners … it wouldn’t be where it is.”

Trevor was not only a talented footballer but also a senior rugby league administrator. He was chairman of the Newcastle Rugby League, on the board of directors of the Knights, the board of MEN of League, and the board of Country Rugby League.

“He was just, you know, a fiercely passionate man that wanted to give back to society, and his number one goal was to give back to the game that he loved so much,” Sandra says.

“The game that brought Trevor so much joy is going to actually take his life. So I think it’s high time the NRL pull their head out of the sand and stop denying what’s going on, acknowledge the people that are suffering and start supporting them.”

Trevor’s legacy

Sandra has made a list of ideas she believes might help other families dealing with CTE and she is keen to put those ideas before the NRL.

“We’ve been promised that they would come up to Newcastle to talk to the people that are making so much noise about something or other to do with head injuries, but nothing – they haven’t turned up,” she says.

“If Trevor had cancer …there would have been a fundraising day, or, you know, they would have done something for him.

“It’s like if you’ve got CTE dementia, you’ve got leprosy, so don’t come near us.”

After the initial rejection of his request, news arrived last week that Trevor would be allowed NDIS funding for 90 days in a community home with one-to-one care, after which his situation will again be assessed.

While this seems like a good outcome, Sandra and her health care team remain on edge about what comes next.

Cousins says the level of care Trevor requires is not always readily available.

“Trevor would require what’s called high-intensity supports, which means he would have access to specialised carers that ideally have more training to be able to manage someone with significant behavioural symptoms,” Cousins says.

If he were to go into a one-on-one, supported, independent-living situation, “it would not surprise me if he ended up straight back into hospital because he assaulted a carer”.

“Because a carer has a right to have a workplace where they’re not going to be physically assaulted when they come to work as well,” she says.

The first 48 hours of Trevor’s new accommodation has been a mixture of highs and lows. His carers operate on eight-hour shifts, which is confusing for him, heightening his volatility.

While Sandra is grateful for the reprieve, she still has serious concerns. “They really don’t know how to look after Trevor. His first overnight stay was with a carer on his first ever shift ...They couldn’t shower him.”

Two days into Trevor’s stay Sandra says, Trevor “smelled”. She arrived at shift change and suggested to the incoming carer “... that I show him what it is to shower Trevor – it takes two people”.

With Trevor physically resisting, and launching at both of them, they managed him into the shower. Sandra instructed the carer to hold both of Trevor’s hands still while she “swabbed him down as quickly as I could”.

“The carer was brilliant but I worry that without me there it could end up in an all-out brawl,” she says.

Dementia is a terminal illness and it is likely it will one day be the cause of Trevor’s early death.

Last month, before heading to Las Vegas for the season launch, Australian Rugby League Commission chairman Peter V’landys revealed the NRL’s record $744.9m revenue for the past year, with a $62m operating surplus.

Crow hopes some of that money might find its way to supporting people like herself and others who are caught in the living nightmare that is CTE dementia.

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout