Phil Gould can make life unpleasant when he doesn’t get his way. While NRL powerbrokers have figured out how to tame his immense power, none have been prepared to deal with his behaviour.

For as long as anyone can remember, Phil Gould has never owned a laptop. They’ve never seen him with a diary. Never seen him holding a sheet of paper.

“I’ve never seen him have an office,” Canterbury Bulldogs coach Cameron Ciraldo says.

A decade ago, when Gould was the Penrith Panthers’ general manager of football and Ciraldo an assistant coach, he’d occasionally set up camp on the lounge in Ciraldo’s office.

“I’d be doing video and I’d hear race four at Moonee Valley in the background,” Ciraldo says. “His memory is ridiculous; he doesn’t need a notebook or a computer. He doesn’t forget a thing – apart from the stories he’s told me 20-plus times.”

Gould’s aversion to desks and stationery won’t surprise those who know him. They understand his weapon of choice is the mobile phone, and he wields his like a sword across a daunting network of billionaires, politicians, police commissioners, TV executives, officials, player managers, and journalists, as much as he detests them.

If you phone Gould – or, more likely, when he decides to call you – there’s every chance he’s in his car, cruising Sydney’s labyrinthine system of motorways and tunnels as he makes his way from the football club of which he’s in charge to Channel 9’s North Sydney studios, to various speaking engagements, to his home at Yowie Bay in Sydney’s south. If you’re on another call, he’ll redial until you pick up.

Mostly, though, he prefers text message. A bombardment of them. In the old Nokia days, he’d underline his point by ending his messages with “LOL”: Laugh Out Loud. In the smartphone era, he’s become an emoji user.

Former NRL chief executives joke that their most meaningful conversations with Gould were often digital, texting endlessly into the night. One tells of the time his wife kicked him out of bed as midnight approached after hours of going back and forth with Gould, a noted insomniac.

The chief executive faced the same dilemma as those before him and since: how do I extricate myself from this conversation without upsetting Gus? “Going to bed, I’m tired, my wife is angry” wasn’t going to cut it.

As the loudest voice for Channel 9 (and, previously, as a Fairfax columnist) prepared to say what others won’t, he imposes his will on the game like no other. A concussion sceptic, he’s the champion of the old-school supporter who laments a code “going soft”. He earns wider respect when he blasts the NRL for strangling matches with video technology and confusing rule interpretations.

‘You don’t f..k with Gus’

You mightn’t like the sound of it, but Gould’s voice is usually one of reason.

In terms of football intellect, he’s without peer. As a coach, he’d won premierships with Canterbury and Penrith in his first four years of senior coaching – before he was 33. He left coaching with the Sydney Roosters in 1999, the club making four of the next five grand finals – the last three with Gould as its coaching director. As Penrith general manager, he simultaneously killed off the AFL’s attempt to steal the hearts and minds of kiddies and their parents in Sydney’s west while setting up a system that has delivered the club four consecutive NRL titles, mostly with homegrown talent.

After years of knocking back approaches from various Bulldogs chairs and directors to save the club for which he played and coached, Gould agreed in July 2021 to become its general manager, reportedly on about $900,000 a season. Like his time at the Roosters and Penrith, the title barely scratches the surface of his influence.

With the financial backing of billionaire pub boss and major sponsor Arthur Laundy, and the monolithic Canterbury Leagues Club (which has pumped more than $6m a year into the football club since Gould’s arrival), he has rebuilt the roster and splashed on infrastructure needed to roll with the big boys of Melbourne, Penrith, Brisbane and the Roosters.

Gould has been so active in the senior and junior player market – for men and women – in recent years that rival clubs are wary of upsetting him. Maybe it’s because of his strong relationship with leading player managers. Maybe it’s because he probably knows the strengths and weaknesses of opposition teams better than they do. Maybe it’s because of his erratic personality. “You don’t f..k with Gus,” one club chief executive says with a laugh.

ARL Commission chairman Peter V’landys knows it. He runs rugby league with an iron fist out of the chief executive’s office at Racing NSW, but Gould casts an equally imposing shadow according to former Nine CEO David Gyngell, whose relationship with Gould was solidified during the Super League war in the 1990s.

“V’landys is the most powerful man in rugby league,” Gyngell tells me. “But Phil Gould is the most intimidating. He’s got his quirks, but he’s one of the most intelligent humans I’ve ever dealt with. And that intelligence intimidates.”

Put it this way: it’s easier to end a call with V’landys than a Tolstoy-like text message conversation with Gould.

For all his intelligence and bravado, there’s a weirdness lurking underneath. Most former players, officials and colleagues tell a story of Gus being their best mate one minute, unaware of their existence the next. Sometimes he’ll say hello, many times he will not.

He’s the type of man to invite you to lunch to discuss a pressing matter, then stare at his phone for two hours. Or regale you with pre-match speeches from his days as NSW’s State of Origin coach that cover you with goosebumps before leaving without shaking your hand. He constantly reminds you of his influence, dropping names and indulging in rugby league gossip. You never know what’s true or why he’s told you.

Often, it’s the silent treatment. He’s known to walk into the Nine commentary box before a game, sit down, put on his headphones and not offer a word to his colleagues until they’re on-air when he springs to life. One tells me he barely uttered a word to him in a decade of working together.

“He’s tripolar!” Nine commentator Ray Warren affectionately describes the man he sat alongside for league’s greatest matches.

Gould doesn’t hide his distrust of the world but celebrates it. “Only the paranoid survive,” is his personal mantra. At 67, as he approaches his 50th season in rugby league, he’s hardly a survivor. Phil Gould is as powerful as ever.

And relevant. The Bulldogs were a broken club only a handful of seasons ago. Gould has transformed them into a legitimate top-four team. He says he could never coach again because he doesn’t understand the modern player, but he understands the modern game better than anyone.

I suspect he understands rugby league better than he understands himself.

■■ ■

Phil Gould was sitting in the main grandstand at Brookvale Oval in the mid-1990s, coaching the Roosters against Manly, who were reeling in a large halftime deficit due to a run of penalties. As international forward Luke Ricketson was marching towards the sin bin, Roosters director James Packer sat next to him.

“You’re going to be the bridesmaid again,” Packer observed. “The ref’s giving it to you.”

“We’ll see about that,” Gould grumbled.

He stomped to the sideline where he instructed captain Sean Garlick to boycott the rest of the match. Cooler heads prevailed, the Roosters held on, but Gould paced the dank dressing-room in fear that chairman Nick Politis was about to sack him.

Instead, Politis burst into the room and wrapped his arms around his coach.

“Say whatever you want about the refs, baby!” he shouted. “I’ll pay all the fines!”

Politis is a Greek-born self-made billionaire who earned his fortune in cars then property. But his passion is the Sydney Roosters, of which he became jersey sponsor in 1976 and chairman in 1993. If V’landys is rugby league’s most powerful man, and Gould its most intimidating, Politis is its most strategic.

For the best part of two decades, he and Gould were the closest of allies, starting in 1994 when Politis wrenched him out of Penrith and made him the face of the eastern suburbs glamour club. When Gould spoke at a dinner in 2018 to celebrate Politis’s 25 years as chairman, his words reduced Politis to tears.

It took just a few days in August 2021 for Gould to put his long and successful relationship with Politis on ice – all because of Politis’s relationship with News Corp journalist Phil Rothfield.

In a late-season match at Suncorp Stadium, South Sydney fullback Latrell Mitchell raced across in defence to stop Roosters centre Joseph Manu from scoring in the corner. He mistimed the tackle and broke Manu’s cheekbone.

In commentary for Nine, Gould insisted the contact was accidental. He doubled down post-match and the following Monday night on 100% Footy. “People want to contradict me or criticise me for what I said,” he bellowed. “But I’ve got the courage and the conviction. I’ll say what I like and I’ll say what I believe, not what someone is telling me to say.”

After receiving an angry call from Roosters coach Trent Robinson, which he revealed on Nine, Gould’s fallout with his former club became bigger than the incident.

What he didn’t reveal was he had accused Politis – via text message, what else? – of “inciting” the media against him. Politis has told many people he doesn’t know what prompted the accusation. He wasn’t quoted, although he had agreed to a request from Rothfield, a long-time Gould agitator, for a graphic photo of the bruised and bloodied Manu in hospital, which ran in News Corp publications.

There’s only one conclusion to draw from this: Gould’s scars from the Super League war – when Gould was a key negotiator for the ARL – still run so deep that he was prepared to end his friendship with one of his closest allies. It also reveals the man: your enemies must be Gus’s enemies and, if they’re not, you’ve betrayed him.

Since those heady events of 2021, Gould has regularly criticised the Roosters on podcasts and on Nine programs. Has it been unfair? Occasionally. Mostly, it’s been brutally honest.

As for Politis, several people have tried to rebuild the bridge, including one player manager who set up a lunch just before Christmas. Politis agreed, but Gould withdrew at the last minute.

A reconciliation of sorts happened in Las Vegas a fortnight ago at the season-opening matches at Allegiant Stadium when the pair ran into each other at a player talent combine. “We’re back to normal,” Politis confirmed.

Those close to Gould tell me they’re not so sure. As long as Politis and Rothfield remain close, their relationship will never be the same.

Gould’s broken relationship with News is well documented, stretching back to Super League before gloriously erupting in the post-match media conference after he coached NSW to victory in the deciding match of the 2004 State of Origin series.

“I don’t deserve the shit youse f..king give me,” Gould fumed. “Not one word of it.” Told by reporters in the triumphant NSW dressing-room of the remark, Blues star Brad Fittler said: “He’s a bloke who holds a lot in. He’s got padded cell written all over him.”

Player scandals and media blame

In time, News Corp has become a convenient scapegoat when Gould wants to “change the narrative” of a story that he doesn’t like.

On the opening day of the 2018 season, I met him in a inner-Sydney cafe to tell him his Penrith coach, Anthony Griffin, had lost the support of some players. He dismissed it as “News Corp trying to get at me”, a line he’s trotted out many times to many people.

I wasn’t working for News Corp at the time, and this wasn’t a conspiracy. Told I’d heard it from players themselves, and some of them had openly discussed their dissatisfaction with the coach with teammates at the World Cup the previous November, he remained adamant Griffin was the right man for the job.

Come August, Griffin would be sacked, and Gould was telling anyone who would listen how he’d taken over the running of the team alongside assistant coach Ciraldo. Several sources at Penrith confirm this version of events. So much for the News-driven hatchet job Gould had told me about five months earlier.

Reputation means everything to Gould. He gives the impression he doesn’t care what people think of him – but he does.

A few days before the 2004 Origin decider, he was invited to an intimate lunch at a Sydney restaurant. NSW sponsor Mark Bouris had organised the gathering – which included NSW premier Bob Carr, captain Danny Buderus, five-eighth Fittler, and Roosters coach Ricky Stuart – to honour the coach, who had declared in his Sun-Herald column weeks earlier that this series was his last.

In the lead-up to game one, players had well and truly kicked on after a “bonding session” at the Coogee Bay Hotel. Some had taken off to The Star casino while others were out so late they were spotted on 9am buses as people headed to work.

When it emerged centre Mark Gasnier had left a lurid voicemail message on a 27-year-old female’s phone, Gould was rocked. He said he didn’t understand young players any longer and, a few days later, declared this series would be his last.

At the lunch, Carr delivered a heartfelt speech before handing him a large gold-and-diamond ring as recognition of his service.

“Origin football has been a very special part of my life,” Gould told the table, tears welling in his eyes.

“I don’t get a lot of raps these days. I suppose it’s a bit like being premier.”

There’s a softer side to Gould that few see. He’s good to his staff, especially those on the least pay. He’s helped many people and genuinely cares about young men and women making the most of their careers. I’ve seen him kiss the forehead of wayward Penrith star Arana Taumata in his parents’ living-room with tears in his eyes, desperate for the kid to stop drinking alcohol and make the most of his career.

“People think he’s ruthless,” Ciraldo says. “But the longer I’ve been able to work with him, the more I’ve seen the human side of him. He wants people to have a better life through rugby league.”

Legendary mood swings

Gould’s favourite TV show is Seinfeld, so much so that he compares himself to the neurotic George Costanza – but he’s more like the Soup Nazi. “He’s not a Nazi,” Kramer observes in that episode. “He just happens to be a little eccentric. Most geniuses are.”

We rarely see the softer side because it’s obscured by the blunt, snarly side throwing punches at whoever he thinks deserves a smack in the mouth. He regularly accuses the media of running agendas, but nobody has a bigger platform nor uses it to their advantage as he does.

His mood swings are legendary, as you’d expect of a big-time gambler with a lifelong love of horse racing.

Just how much Gould has gambled on horses over the decades has been a source of great speculation, but you need only look at the enormous gold-and-diamond ring in the shape of a horseshoe on the fourth finger of his left hand giving Frank Underwood vibes to understand his devotion to the punt. It’s the result of a significant win on the Golden Slipper. The ring Carr gifted him at lunch that day is never in sight.

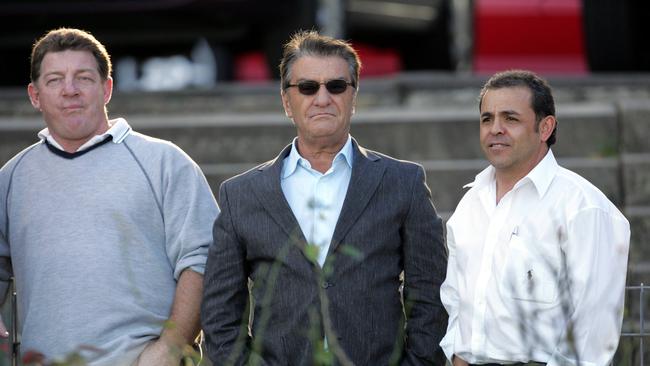

Gould also owns shares in horses and was part of a syndicate that included his friend, Damion Flower, a prominent owner and breeder whose big break came via champion sprinter Snitzel. Unbeknown to Gould as he attended race meetings and NRL matches with him, Flower had another syndicate going: the mass importation of cocaine via his connections at Sydney airport.

When Flower was arrested in 2019, Gould was genuinely shocked, according to colleagues, friends and racing industry participants. He had nothing to hide but was paranoid about police surveillance. If he discussed the matter with someone, he would push their mobile phones to the corner of the table.

Gould’s relationship with Flower was mentioned in almost every story that followed, but he didn’t abandon his friend. “I just can’t believe it,” he told The Sydney Morning Herald after the arrest. “I am hoping it’s not true. I’ve been sick all day.” In 2022, Flower was sentenced to 28 years in prison after pleading guilty to the importation of 228kg of cocaine into Sydney.

Relationships are important to Gould, although they’re transactional. If you’re a reporter, you’re a means to an end. He regularly claimed “the media is obsessed with me” during his time at Penrith, oblivious that underpaid reporters were simply driving 60km from their newsroom in the city to Penrith’s training facility for the mileage imbursement.

In some respects, though, he’s right: the media does infatuate itself with Gould, whether it’s the good, bad or weird. All successful coaches are complex, but he makes for fascinating, colourful copy.

He’s the master of suspense. In 2011, when his hair mysteriously went white within a matter of weeks, speculation spun out of control about his health. Instead of clearing the air, he waited a year before revealing he had an auto-immune disease. “When it happened, I went, ‘Oh well, that’s different’,” he said.

Over the years, Gould has stared down various medical ailments, some requiring surgery, although even his closest friends aren’t sure what for. “I’m dying,” he tells them. “But aren’t we all?” In recent years, he’s undergone dramatic weight loss. Colleagues suspect he’s using Ozempic or something similar.

If you really want a snapshot into the relentless, capricious mind of Phillip Ronald Gould, check out his X account and strap yourself in for a wild ride as he provides for his 70,000 followers team updates, breaking news, questions climate change, talks about his hate of paper straws but admiration for US President Donald Trump. (It’s rumoured Gould lost a hefty bet on Trump to win the 2020 election.)

“Who came up with the idea of putting your steak or schnitzel on top of your chips and veggies?” he posted in 2022. “Makes all the chips soggy. Why do they do this? Did we request this? Did I miss a meeting?”

Sometimes, he outsmarts himself. Last year, he posted the incorrect venue for the Bulldogs’ finals match against Manly before the NRL had locked in its schedule. A few days later, another post slammed media speculation about winger Josh Addo-Carr testing positive to cocaine in a random roadside drug test. “There is absolutely no truth to rumours that Josh had any issue,” Gould insisted. “None whatsoever.”

In response, NSW Police issued a media release revealing Addo-Carr had indeed tested positive. Gould called a snap media conference at which he shifted focus back to the player, making it clear the 29-year-old had misled him.

“Well, that’s the other part, did he lie to us?” Gould asked reporters. “I’m convinced in Josh’s mind that he didn’t think we’d ever hear about this.”

Falling under his spell

Rugby league journalists mock the juvenile way Gould blocks, then unblocks, then re-blocks them on X. When he blocked me in 2022 without any explanation, I vaguely sensed we had a problem.

For years, we’d shared a strong relationship, particularly when we were both writing for the Herald. It was easy to fall under his spell, as countless have before. It’s hard not to agree with Gould’s commonsense views on the game.

He was also someone you felt you could trust with your deepest, darkest secrets. It’s the coach in him. Talking to Wayne Bennett feels the same. “Nothing can shock me,” Gould once told me. “I’ve coached footballers for years. I’ve seen it all.”

Then he just went cold, failing to return calls or messages for weeks. I fronted him in the green room at Channel 9 before shooting 100% Footy one Monday evening and asked if there was a problem.

“No,” he grunted. He barely acknowledged me on-air for the rest of the year and, on one occasion, asked, “What’s your name again?”

Those who fall out with Gould often don’t know why, although life is much easier outside the tent than in. It’s exhausting engaging with someone so preoccupied with themselves and their place in the world.

An example: in April 2022, he randomly sent me a screenshot of a social media post from a Newcastle Knights supporter: “Gus Gould is manipulative, agenda-driven, overpowering, too influential in the game, and gets his way too often. His conflicts of interest assisting teams he’s associated with is unfair and threatens the integrity of the NRL. Is there any chance of him coming to the Knights?”

Several attempts were made to talk to Gould for this piece. He was the first person I called before I sent two text messages explaining why I was reaching out. He never responded.

■ ■ ■

The AFL never saw Phil Gould as the enemy. Few from that time can remember him being mentioned in commission meetings, if he was spoken about at all.

What most AFL people don’t understand is how a general manager of football has more power within a club than the chair or chief executive.

When the AFL decided in 2010 to pick a fight in rugby league’s backyard – Sydney’s western suburbs – it did so by stealth. The signing of rugby league star Israel Folau made a lot of noise, but the AFL was careful with its messaging: the GWS Giants weren’t an alternative to Parramatta, Penrith, Canterbury and Wests Tigers, but another team to support. Your AFL team.

At the same time, the AFL was infiltrating local councils and schools. Giants coach Kevin Sheedy wrote 5000 letters to primary school children as Australian rules goalposts began sprouting in suburban grounds in Sydney’s west.

Gould, who in May 2011 had joined the Panthers as their general manager, characterised the goalposts like they were the tripods from HG Wells’ War of the Worlds, and with some justification. The NRL almost seemed disinterested in thwarting the incursion of its heartland, claiming it was a NSW Rugby League issue. It also didn’t have the money to take on the AFL.

An “independent commission” would take control of rugby league in February 2012, dissolving the partnership between the Australian Rugby League and News Corp, but Gould couldn’t wait that long to act. He started lobbying commissioners before they had even started. He drove advertising executive Ian Elliott, one of the incoming ARLC directors, around the grounds of western Sydney, pointing out Australian rules goalposts where rugby league woodwork had once stood.

The following year, he invited the commission to a meeting at Penrith Leagues Club where he bluntly laid down his vision for the west. Gould was fighting the good fight for his code, but what he specifically wanted was funding. He argued the money belonged in the back pockets of the four western Sydney clubs because they knew their pathways better than the NRL.

“The sky was falling in, according to Gus,” recalls one commissioner. “There was no doubting his passion for the game, but his delivery was over the top.”

ARLC chairman John Grant barely showed interest in Gould’s claims, according to commissioners and executives from that time. He had every right to be suspicious. The Panthers Group was floundering beneath $90m of debt and on the brink of insolvency. Panthers sold off some of their leagues clubs and assets but desperately needed $10m to stay afloat.

Gould picked up the phone to James Packer, who wrote the cheque on the spot. “He only did it because of his friendship with Phil Gould,” former chairman Don Feltis said in 2020.

With Packer’s assistance, Gould turned Penrith into a juggernaut on and off the field. In 2016, the club opened a $22m academy funded entirely by the Panthers Group. He walked then prime minister Malcolm Turnbull through the building before delivering a stinging rebuke to rugby league powerbrokers.

“Western Sydney people will understand the NRL are fair dinkum about them a lot more when they actually invest in the west,” he said. “I want to make sure the people of western Sydney feel like the NRL cares about them.”

Conflict with NRL bosses

Gould isn’t the first to impose his will on rugby league bosses, first ingratiating himself with them before turning on them when he doesn’t get his way. The difference is few have a media voice as loud and influential. He can make life unpleasant.

Decades ago, he regularly drank schooners with former NRL chief executive David Gallop at the Clovelly Hotel in Sydney’s east with a group of officials and agents colloquially referred to as the “Clovelly Mafia”. During matches, Gould would randomly text Gallop and other powerbrokers when he decided the code was in a healthy position: “Stop everything, the game is perfect.” The happy vibes rarely last. In the end, Gould’s relationship with Gallop soured, culminating in an infamous Triple M interview at Accor Stadium in 2008. When Gallop walked into the commentary box, Gould didn’t acknowledge his presence, staring out the window until the microphones flicked on before blasting the NRL boss for 11 minutes about the state of the game.

‘I took many calls about Gus, but I didn’t listen to any of them – because Gus is special.’

In many respects, Gould is rugby league’s squeaky wheel, highlighting the game’s various problems. Throughout the 2000s, he exerted influence through columns for Fairfax (now Nine) and in game-day coverage for Nine. In recent years, he’s been increasingly edged out of the commentary box to make way for retired players Andrew Johns, Billy Slater and Cameron Smith, but he’s found a new voice in podcasting.

The platform that really gives him power is 100% Footy, a panel show with retired Cronulla captain Paul Gallen aired on Nine on a Monday night since 2018. It allows him to set the agenda for the week, machinegunning the game’s administrators, match officials, the match review committee, the judiciary, the Bunker and “you blokes in the media”.

Whether they like the man or not, supporters appreciate his perspective.

NRL officials, club bosses and coaches aren’t so warm to the idea because Gould wears two hats: club official one minute, outspoken commentator the next. Conflicts of interest are common in rugby league: board members, assistant coaches, consultants and player agents fill endless radio and television panels.

But Gould is accused of overstepping the mark more than others because of the strength of his voice and what he has to say. Gyngell, during his time as Nine chief executive, was regularly on the phone with irate NRL officials steaming about something Gould had said.

“I took many calls about Gus, but I didn’t listen to any of them – because Gus is special,” Gyngell says. “It’s important to defend the great ones. That’s on me more than anyone else. We’d have rigorous conversations, and sometimes disagree, but if I wanted something to happen, he would back me.”

NRL powerbrokers eventually work out how to handle the Power of Gus, but none have been prepared to sanction him when his broadsides as a commentator mean he breaches the rules as a club official. It’s a wordy edict: “No person bound by the code shall engage in any conduct which is detrimental to, brings into disrepute, is inconsistent with, is contrary to, or is prejudicial to, the best interests, image or welfare of the ARLC, the NRL, the NRL competition, the related competitions, the representative competitions, the clubs or the game.”

The rule is applied at the NRL’s discretion. Club bosses whose coaches and players have been slapped with $10,000 fines for public remarks that have “brought the game into disrepute” have long questioned why Gould receives special treatment. The short answer is fear.

In 2023, NRL chief executive Andrew Abdo started the process of going where few have gone before, meeting with Bulldogs CEO Aaron Warburton after Gould discussed a judiciary matter involving forward Jacob Preston. Gould had also blasted the NRL as “stupid” for failing to give the Bulldogs salary cap relief for captain Josh Jackson, who had retired the previous season but was given a strength and conditioning role at the club. Under NRL rules, a portion of his contract had to be included in the Bulldogs’ 2023 salary cap.

Each time the NRL rejected applications for the amount to be waived, Gould became more aggressive in his criticism of head office. At times, it felt like he was daring Abdo to breach him. On May 2 last year, Abdo did.

On 100% Footy, Gould again blasted the NRL as “stupid” after a decision to disallow a try to Wests Tigers captain Api Koroisau in a match against Brisbane. “Our game’s so stupid,” he said. “You can lose the ball over the line and it costs you 20 metres and seven tackles. Why? I don’t know because it’s stupid, but I can just take a line dropout, and it goes out on the full … no consequence. It’s nothing at all. What sort of stupid game is this? Who sits and makes up these rules?”

He said it with a tone of faux outrage. And he was right: the obstruction call on Koroisau was stupid. But the repeated use of the word infuriated the NRL. Abdo handed him a $20,000 breach notice with half suspended over two years. Gould immediately said he’d fight it.

The NRL had the backing of the clubs, but Gould had the support of the public, who argued he had a right to speak his mind and agreed with his remarks.

In other sports, Gould’s comments would never fly. Last August, retired NFL great Tom Brady was issued with a score of restrictions around what he could say in his new role as a Fox Sports analyst. Because Brady had bought a stake in the Las Vegas Raiders, he was forbidden from criticising other teams, let alone match officials.

According to those at Nine, Gould’s lawyers whipped in a “100-page” response to the NRL’s breach notice and, by September, the entire fine was suspended. Gould has been measured in his criticism of the NRL since, but there’s no question he’d won the battle. Certainly, club bosses believe the NRL had been spooked.

There was a belief that Peter V’landys had driven the sanction, but he denies it. “It’s a conflict, you can’t hide from it, but if anyone can handle it, Gus can handle it well,” V’landys says of Gould’s dual roles.

Whether it’s in rugby league or racing, V’landys wears his combative nature as a badge of honour. He once called South Sydney chief executive Blake Solly a “flea f..ker” in a meeting of club bosses and proudly confirmed it when I asked for comment.

With Gould, V’landys seems wary and uncertain of where he stands. He was surprised in late 2022 when I contacted him for comment about Gould attacking him, Abdo and Rugby League Players Association chief Clint Newton at a Leagues Club Australia function on the Gold Coast in front of 450 people because of never-ending collective bargaining agreement negotiations.

“Gus and I have never really been offside from my understanding,” V’landys says.

“The only real disagreement is when I took a stronger stance on head high tackles.”

He’s referring to the 2021 headhigh crackdown rushed in hours before Magic Round kicked off in Brisbane. V’landys had done so amid concerns the game wasn’t vigilant enough on concussion, but it was done so hastily it confused match officials, who sent off players all weekend for minor contact. Gould was furious, blasting the NRL in commentary and then in a fiery one-on-one interview with V’landys. A week later, he doubled down.

“It didn’t make the cut last week, but I asked him, ‘How would you tackle Jason Taumalolo? Kikau?’” Gould told viewers. “He said, ‘I’d tackle them around the legs’. I said, ‘You wouldn’t last two minutes’ … The people who are making these decisions don’t understand the game.”

V’landys reports the pair, at the time of writing, are on good terms. Gould met with him earlier this year to talk shop.

“He’s the guy you’d want at a dinner party,” V’landys says, before adding with a chuckle. “He says things others won’t.”

■ ■ ■

One of Phil Gould’s favourite stories is about the night he had dinner with Nine Network owner Kerry Packer. At the end of the night, the richest man in the country offered to drive Gould home in his limousine.

They listened to the bawdy comedy of Rodney Rude with Packer roaring with laughter for the entire trip. Gould got out of the limo and caught a taxi back to the restaurant where his car was still parked.

As a football administrator, Gould has followed one of Packer’s key principles: “The bigger the problem, the more money you throw at it.”

He joined the Bulldogs with their salary cap in disarray, with big-name but underachieving forwards such as Luke Thompson and fiery Tevita Pangai Junior Jr on contracts worth telephone numbers. He barely disguised this fact when privately discussing his move to Canterbury.

“I’m not sure I can fix it,” he’d say, echoing the same line he had uttered in his early months at Penrith.

It’s a time-honoured Gould play: paint a picture of chaos, set the bar low, look like the Messiah when he turns the club around.

Gould just doesn’t come at a hefty price of upwards of $1m a year but also demands the football club throw money at the problem, as per Packer’s advice. NRL clubs must work under a football expenditure cap of $5.45m a year. If they breach it, they pay a levy.

Junior pathways are exempt from these rules, meaning rich clubs can flood the market and snap up the best players from a young age. It’s impossible to work out how much Canterbury is spending on pathways and development, but rival clubs estimate it’s a ballpark figure of $5m annually. (The Bulldogs insist the most they have spent is $4m).

Clearly, Gould wants to replicate the sustained success at the Bulldogs as he did at Penrith, but with a far shallower talent pool. He’s told other clubs it’s an unsustainable model but not against the rules, so why stop?

Bulldogs fans already feel like he’s saved their club. Crowds and memberships are up.

“It’s absurd how much momentum he’s generated,” says one club chief executive.

He’s done so by overhauling the roster and filling vacant spots with some of the Panthers’ finest. He also plucked Ciraldo out of Penrith. For three years, the 40-year-old was deemed the next big thing in coaching. He rejected chunky offers from several clubs to join Gould’s Belmore revolution.

“I trusted him and I knew he knew how to build a successful club,” Ciraldo says. “But more than anything I knew I needed help if I was going to be an NRL coach, and I couldn’t think of a better mentor than Gus.”

He must have had reservations about taking the job, however, because of what happened to Ivan Cleary.

After coaching him as a player, then giving his first coaching job at the Roosters, Gould was once Cleary’s biggest fan. He lured him from the New Zealand Warriors in late 2011, certain Cleary could turn the Panthers into a premiership force.

Within three years the relationship had broken down. Gould called Cleary’s wife Bec to tell her he thought her husband needed a break from coaching – while Cleary was on a plane returning from a match. Cleary pushed back but was sacked weeks later.

Since then, Gould has spun a line that Cleary was holding back his talented son, Nathan, from playing at the top level because Cleary feared accusations of nepotism.

The reality, according to those at the club, is their relationship fell apart when Cleary started to question Gould’s decisions, specifically around recruitment and retention. “He did so much good for me,” Cleary said of Gould in his recently released book. “But he hurt me, too.”

When Cleary returned to Penrith in 2019, he did so on the condition he didn’t have to answer to Gould, who left a few months after his arrival. It came at a turbulent time: a sex-tape scandal implicating several players had flared on the eve of the season and it exposed a trashy culture within the club.

The fingers were pointed at Anthony Griffin for the plummeting standards in discipline, but it also happened on Gould’s watch. How did the smartest man in the room, in the entire rugby league cosmos, not see this earlier?

At the end of that season, with Gould no long casting a shadow over him, Cleary cleaned out the roster, reset the culture and set standards never seen before at Penrith. The payoff has been four consecutive premierships, the best since the legendary St George teams of the 1950s and 1960s.

Surely, Ciraldo took the job at the Bulldogs knowing of the rollercoaster of emotions Cleary had experienced under Gould?

“It never crossed my mind,” he says. “The only thing that crossed my mind was if we could build a successful club and I believed we could. It takes time to build strong working relationships, and we’ve been working together for over a decade. I feel like we’re working better together now than ever before. It all comes back to trust, and that takes time.”

Nevertheless, coaches under Gould have a limited shelf life. They feel his glare from the grandstand as he runs an eye over training. They know they’re on the outer when he stops taking their calls.

He’s overseen the departure of several: Ricky Stuart, Matt Elliott, Ivan Cleary, Anthony Griffin, Trent Barrett … All left for different reasons, but none stronger than the fact they will never be as smart as their boss.

“Nobody is bigger than the club,” he insists each time.

You sure about that?

More Coverage

Andrew Webster is one of the nation's finest and most unflinching sports writers. A 30-year veteran journalist and author of nine books, his most recent with four-time NRL premiership-winning coach Ivan Cleary, Webster has a wide brief across football codes and the Olympic disciplines, from playing field to boardroom.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout