The NRL’s official concussion study allegedly did not warn rugby league legend Robbie O’Davis that a scan showed signs of brain injury, nor alert the families of two other retired champions they had been diagnosed with dementia during the research.

A three-month investigation by The Weekend Australian has uncovered an alarming number of former Newcastle Knights champions suffering early-onset dementia as well as serious concerns from their families and a top neurologist about the research protocols of the NRL-funded study, which has been hyped as a “milestone” for the sport’s treatment of long-term head trauma.

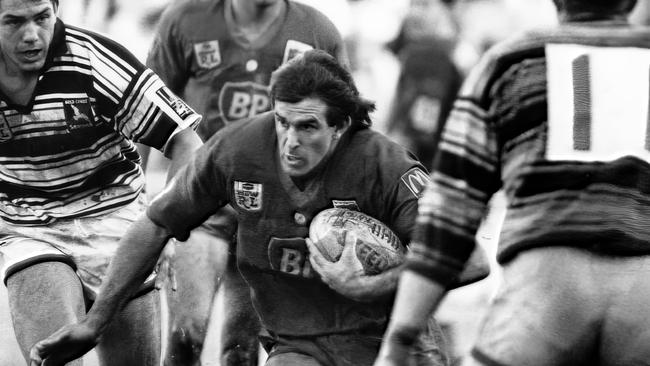

Clive Churchill medallist O’Davis, 50, finally learned in April he is suffering “probable” chronic traumatic encephalopathy– dementia that his neurologist believes related to repeated head knocks.

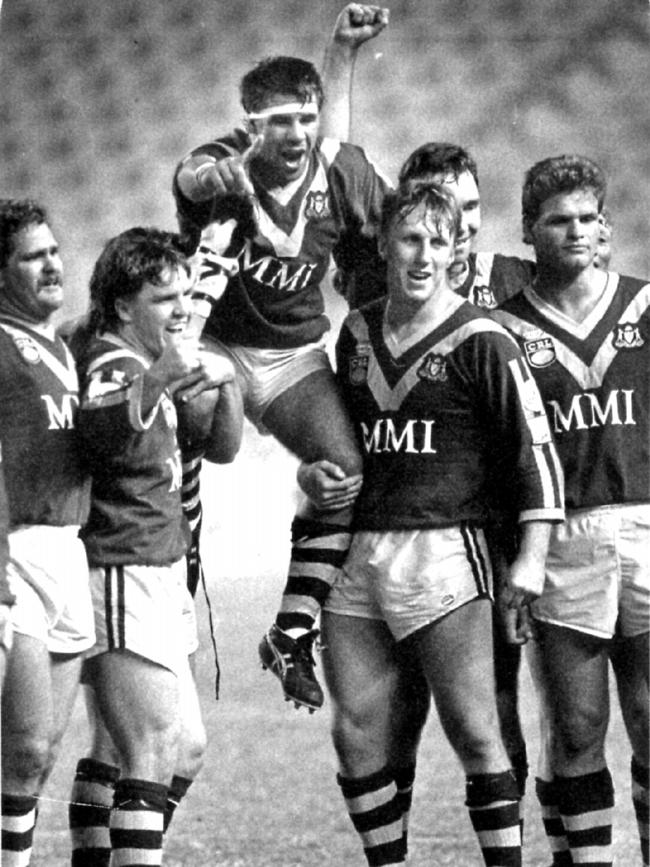

Knights foundation player Glenn Miller was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s at 54, and legendary club hard man Marc Glanville, 57, who believes he has dementia, went into an explosive rage so terrifying he was recently admitted to a psychiatric hospital.

Former St George player Trevor Crow, who as chairman of the Newcastle Rugby League helped draft concussion guidelines, is also suffering early-onset dementia and has become “childlike” at the age of 59.

O’Davis and the devastated families of his fellow ex-players spoke to The Weekend Australian because they were troubled by their experience with the NRL’s concussion research project, led by Dr Andrew Gardner and Professor Chris Levi, and have deep concern about the code’s support for what they warn is an “epidemic” of footballers suffering CTE.

O’Davis said he took part in the study in 2018 after being contacted by Dr Gardner, having reached out to the NRL because he was suicidal and feared it was connected to repeated head injuries during his career.

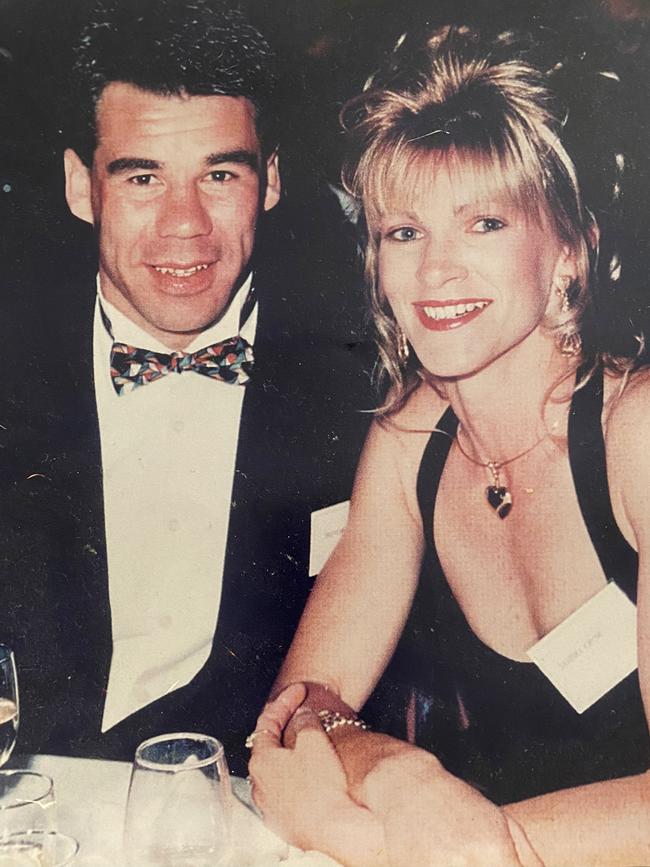

The two-time premiership champion, who also starred for the Maroons and Australia’s Kangaroos, underwent a brain MRI but alleges he was not told the results of the 2018 scan until independent neurologist Dr Rowena Mobbs reviewed it in April 2023.

A devastated O’Davis says he was denied four years of potential treatment, while wife Louise was furious having spent years unable to understand her husband’s moods and behaviour.

“When I did the MRI (scan) I said I would only do it if they (the NRL study researchers would) let me know the results and they said ‘OK’,” O’Davis told The Weekend Australian.

“I really, really wanted to know (the results) because I wanted to know if it was just me or if there was something wrong with me.”

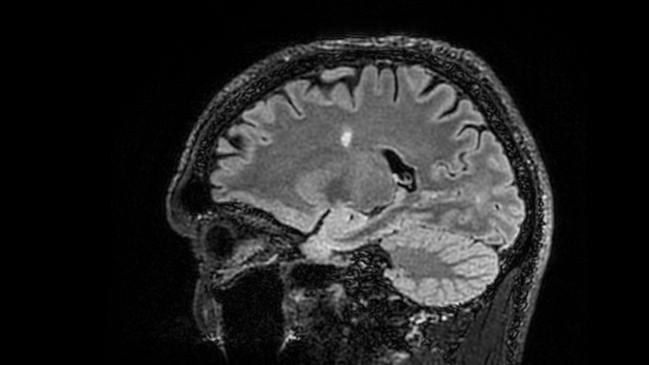

Dr Mobbs confirmed to The Weekend Australian that in her view the 2018 scan undertaken for the NRL’s study showed trauma-induced brain injury and she has since diagnosed him with “probable CTE” based on a behavioural and cognitive assessments, as well as scans in line with internationally accepted criteria.

“Robbie sought to understand if he had signs of brain injury from football, and I felt it was important he be informed of his results so that he and his family could seek the support they desperately needed,” Dr Mobbs said.

“In my opinion, his scans suggested cumulative brain damage and probable early dementia, in line with his cognitive evaluation that indicates likely CTE. Robbie’s result struck me as abnormal for someone so young. We have since looked at stabilising his mood and behaviour, and will continue to monitor his long-term cognitive functioning.”

Dr Mobbs said she was concerned O’Davis was never told about his MRI results.

“It raises deeper questions about the research protocols,” Dr Mobbs said. “Any time in research where there is a scan with a clinical abnormality, the researchers have an obligation to disclose that to the participant.’’

Citing patient confidentiality, Dr Gardner declined to respond to direct questions from the Weekend Australian about whether he informed O’Davis about his MRI results.

A Sydney University spokesperson reiterated that “potential conditions are identified as a result of the study” and would be conveyed directly to the participant.

“Professor Gardner has confirmed these processes throughout the study have remained consistent,” said the spokesperson.

Dr Gardner said his “priority” was his participants and their “privacy” was paramount, and wouldn’t comment on individual cases.

“So I can’t speak about anyone’s personal situation publicly,” Dr Gardner said. “I’m of course happy to meet any of our participants with their families privately to help clarify and answer any questions. Our research program continually reviews our processes and we hold ourselves to the highest standards, as is expected of us from everyone involved.”

Dr Gardner and Professor Levi – who began studying players’ brain health with the Knights’ support in 2012 and have received $250,000 annually from the NRL since 2019 to expand their work – say their research aims to find out whether former NRL players have more psychological disorders, cognitive problems and brain changes compared to the general community, and to prevent the risk of “misdiagnosis” of CTE.

The duo – associated with the University of Newcastle and University of Sydney – currently advise some of the NRL’s biggest names, including Knights star Kalyn Ponga, and the Australian Rugby League Commission on its concussion protocols. Dr Gardner, a neuropsychologist, is also Rugby Australia’s chief concussion adviser and an expert for the AFL and World Rugby.

In 2019, when announcing the annual funding boost, then NRL CEO Todd Greenberg declared it was a “milestone moment for rugby league”, which would “give experts better insight than ever before into head injuries”.

The study was promoted not just as a research program, but also to help former players.

Dr Gardner said his study would “allow us to identify problems and immediately refer former players for treatment”.

A consent form for participants, seen by The Weekend Australian, shows footballers can “request an individual summary” of their “assessment results” including MRI brain scan results.

What kind of study’s this?

Sheree Miller said she was “horrified” to learn in 2021 that husband Glenn had been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease by the researchers three years earlier – but the family had no idea. She claimed the diagnosis had not been shared with her husband’s GP.

She recalled the day in 2018 that Glenn returned from Dr Gardner’s testing and she asked the ex-Knights player how he went.

“Glenn said ‘they said my memory was normal for a 54-year-old’,” Sheree said. “I recall laughing and saying ‘Oh, they need to spend a day in my life’.

“I just said: ‘What are they studying?’ and didn’t question it any further.”

Mrs Miller told The Weekend Australian that by March 2021 her husband had “shockingly” declined and they visited Dr Gardiner together. “After the testing was completed Andrew said, ‘Oh, okay, so your Alzheimer’s has progressed (from 2018),” Mrs Miller said. “I was just sitting there and I questioned, Oh, hang on, what? Sorry, what are you talking about? In 2018? And (he) sort of confirmed that he told Glenn in 2018.”

“What? You diagnosed this in 2018?” she recalls saying to Dr Gardner.

“I threw a hissy fit in (Dr Gardner’s office) and said ‘what kind of study is this?’,” Mrs Miller said.

“Is Glenn another statistic? What are you doing for the participants? How many other men are going through this?”

Mrs Miller said her husband had been left unmedicated for three years.

Mrs Miller said Dr Gardner was “really lovely ” and “took on board what I was saying”, and she was so distressed she “can’t even remember what he said to answer her questions”.

Mrs Miller said because of her husband’s dementia she could not determine if her husband had been informed of his 2018 MRI and he had “forgotten” or had chosen to keep it from her, but said medical documents showed “no report” was produced for it.

“He was told then (2018) apparently he had very early signs of Alzheimer’s,” she said.

‘I scared myself’

Marc Glanville told The Weekend Australian he has been involved in the NRL studies for “over a decade” and believes he has dementia, and possibly CTE.

He said he was recently admitted to a psychiatric hospital after experiencing a rage, which gave him a “fright”.

“I scared myself a bit,” he said. “My wife was on the end of that.”

Two family members confirmed the psychiatric admission.

“My family are a bit worried,” Glanville said. “Chris Levi said I possibly had some sort of CTE, but he can’t be 100 per cent … I think that’s the case.”

Several members of Glanville’s family confirmed they have not been told, or been given a diagnosis from NRL researchers, despite the repeated testing.

Jordan Glanville, the daughter of Glanville, whose memory started to fail in his mid-40s, is also pleading for the researchers to consult family members “so we can help him as he continues to decline” and to provide “real world” information to the study.

Ms Glanville, an occupational therapist who also plays rugby league, said the NRL researchers should be involving family in their study because they “would be able to provide better insight into what’s going on”.

“I think it could help in a number of ways being involved in the study,” she said.

“Because my dad’s not always honest when he’s asked questions by a doctor about his day-to-day functioning or if he’s been easily irritated or easily agitated – and part of that could be denial; part of it just could be that he doesn’t see it is like that, because of this disability.”

Ms Glanville says if families were involved they could have more open conversations about behaviour and other changes. “He wouldn’t be able to say: ‘oh, everything’s fine or yeah, had that scan and nothing’s wrong’,’’ she said.

Ms Glanville said what had started out as short-term memory loss has culminated in explosive rages and her father moving out of the family home.

The family needed to know his diagnosis “so we can help him as he continues to decline”, she said.

“We live in the real world with them. We could give the researchers a clear picture of what is happening in the home.’’

Ms Glanville said she did not believe her father was able to provide continued consent to be part of the study.

“A family should be given guardianship in these situations. A family member should be going to this testing with them,” she said.

Her dad forgets to attend medical appointments, can’t remember what he is being tested for and has refused to take his medication.

“He’s getting worse,” Ms Glanville said. “I know what he’s like and how quickly he could react to a situation that is completely out of control, which means he could then put somebody else in danger or a risk in the community.”

While a psychiatrist had diagnosed Glanville with a “mood disorder”, his daughter said she was in no doubt he had dementia caused by the head injuries he had endured in his football career.

She now fears for his future and safety.

“My dad is a completely different dad to who he was 10 years ago,” she said.

In 2019, a candid Glanville told the SBS program Insight he “did not want to end up like my father was” – who he suspected had CTE.

Glanville said his father’s symptoms, including “violent outbursts” were “appalling” and he “did not want his family to go through that”.

‘He is abusive’

As then chairman of the Newcastle Rugby League, Trevor Crow’s first dealings with Dr Gardner were aimed at preventing other footballers suffering the type of head injury harm common in his era as a player, which included three seasons at St George (1988-90) as well as captaining the NSW Country team.

The pair worked together developing head injury and concussion guidelines for the Newcastle competition in about 2013, but by 2016 Crow had changed from being “the man of the house” to “pretty much quitting life”, wife Sandra said.

Mrs Crow said she initially thought her husband was having a “nervous breakdown” when he turned 54. Early symptoms included outbursts of anger and short-term memory loss, and now he can no longer work.

“He was just, he’d become a really angry man,” Mrs Crow said. “The first sort of signs that there was something wrong were the depression and the anxiety and the paranoia, the forgetting things, forgetting people’s names. And all of a sudden his language started to change. So he struggled to be able to talk.

“His behaviour is very childlike. He slaps himself in the head, he can’t string a sentence together. He can’t write. He is abusive. Paranoid. He has high anxiety.

“He doesn’t know how to shower or change his clothes. He has delirium where he doesn’t know where he is.”

In 2019, Mrs Crow was alerted to a “football study” at Newcastle University with Dr Gardner.

She said Dr Gardner was “mortified at Trevor’s decline” in the handful of years since they had worked together. Crow was tested at the Mater Hospital in July 2019, a process his wife said was “the most punishing, painful thing I’ve had to sit through”.

Mrs Crow said no one reached out to inform them of the results of the scans or the cognitive results.

“We never got the results of that scan, I thought ‘it can’t be too bad, we never heard’,” she said.

In September 2019, two months after the tests, Mrs Crow contacted the clinic and “lobbed over there” with her husband, then aged 57, to get the results.

“Trevor couldn’t even remember who Andrew Gardner or Chris Levi were.”

The NRL study researchers told the Crows Trevor had a “thinning of the frontal lobes and that it was dementia”.

Mrs Crow was rocked by the news. “Where do we go, what do we do?” she said she asked the researchers. “When I asked about treating his mood and depression, I was advised to see a psychiatrist. The psychiatrist diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s.”

Mrs Crow said she asked Dr Gardner if her husband had CTE.

She alleges he said: ‘No, not CTE, it’s just dementia’.

The exchange left Mrs Crow confused. “As far as I was concerned that was the reason we were there (the NRL study) because of Trevor’s concussions in football,” she said. “He had then developed dementia.”

Despite Dr Gardner allegedly telling Mrs Crow her husband did not have CTE, a letter seen by The Weekend Australian reveals that Professor Levi was not ruling CTE out. “This neurodegenerative condition has occurred on a background of a high-level rugby league career with around 15 years of play at an elite level. So of course the issue of concussion and the possibility of chronic traumatic encephalopathy as the underlying pathology is a matter of academic interest,” he wrote to her lawyer on October 21, 2019.

Mrs Crow said she didn’t know if Trevor, now 61, was still in the NRL study. “You feel so alone because no one is checking in on you, there is no follow-up,” she said.

“You don’t hear from them after the study. It was only when I was reaching out for things that I really got any replies.”

With her husband unable to work – he can’t write or verbally communicate properly – she is under immense financial and emotional strain trying to care for him.

“I’m angry, I have the most f..ked-up life ever, it’s not what I asked for, I want my normal husband back to doing normal things,” Mrs Crow said. “You know what happens when people have accidents on worksites? How is it any different?”

NRL view

In March the NRL’s chief medical officer, Dr Sharron Flahive, publicly stated the NRL research was reassuring for many current and former players.

“You will see that there are many players who, through testing, get a lot of comfort from the fact that they find their tests are actually normal,” Dr Flahive told the Senate concussion inquiry. “Anyone who’s played a contact sport starts to get worried that they may have some cognitive decline, and so this is a big support.”

The Weekend Australian sent detailed questions about all four ex-players’ involvement in the study to Dr Gardner and Professor Levi, who referred them to the University of Sydney.

A university spokeswoman said: “Individual feedback on a participant’s own cognitive assessment study results is … available only to them, on request. “We also know family and friends want the best for their loved ones, and the wellbeing of our participants is always our prime concern.

“This includes protecting their privacy, which we take extremely seriously. Our researchers are required to abide by their legal and ethical obligations and can only provide individual study results to a third party if the individual participant has specifically provided consent for that to happen.”

The university declared that if any potential medical conditions were identified in the research, the participant would be informed “privately and directly”, and with verbal consent “their nominated general practitioner is also informed of the findings to help the participant determine the best course of action, including potential external support and healthcare options”.

The spokeswoman said the research was designed “so we can all better understand how head impacts might affect players later in life” and former players who were part of the study “typically choose to do this for the benefit of current and up-and-coming players”.

The researchers were legally unable to comment on “individual circumstances” but adhered to a strict policy of academic research integrity “with oversight by our ethics office”.

Sydney University said they could only comment on Dr Gardner’s research activities from November 2021 when he commenced as a research affiliate.

Newcastle University declined to comment on research undertaken by Dr Gardner prior to November 2022, referring all enquirers to Sydney University.

The NRL also backed Dr Gardner and Professor Levi’s work and said it “will transform our understanding of later-in-life brain health in former NRL players”.

“Further, it aims to advance knowledge and potentially improve healthcare for former athletes from other contact and collision sports,” an NRL spokesman said.

‘War zone’

The Weekend Australian spoke to dozens of rugby league players and their families on and off the record and they declared there is a desperate need for more support for ex-players suffering CTE.

“It’s a war zone,” Mrs Crow said. “It’s an epidemic.”

Some wives were now “dipping into super”, mortgaging houses, and postponing retirement to support their husbands.

One wife, who declined to be named, called CTE the “arsehole’s disease” because of the way sufferers’ behaviour changed.

Mrs Crow revealed she is frightened of her husband. “I’ve got strategies in place. If, you know, Trevor gets quite aggressive. I’ll go call the police … I know that if I feel unsafe, I can’t have him living at home anymore.”

Mrs Miller echoes that.

“I don’t feel unsafe physically,” she told the Weekend Australian. “I feel unsafe emotionally, and I feel unsafe because I’m not supported … if we decide one day we can’t cope and have a breakdown, where does that leave him?”

The wife of a Newcastle great, who declined to be named, said the NRL had to get information to families about what signs to look out for, because otherwise they thought they were going “mad”.

“He was eating panadol and nurofen, that was the head pain,” she said. “We stopped buying them. We had no idea what was going on. You feel like you are travelling on your own, they are masterminds of deception.” She described how her husband told her he “didn’t have a problem” and still doesn’t think so now despite his severe mental decline.

Numerous families spoken to by The Weekend Australian are calling for more transparency, information and support from the NRL.

“I felt like my husband has been put out to pasture to die,” Mrs Crow said.

“I wanted to know what had happened to my husband. Why had he changed so drastically? Why are our lives so full of destruction now?”

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout