Worker-owned care firms could bring services to rural and remote areas

Worker-owned firms could be the solution to a lack of aged and disability services in rural and remote Australia. A new pilot program will find out.

Solving the shortfall in aged and disability care, especially in rural and regional Australia, might come down to helping care workers and community groups band together to form their own “social care” firms as they do in many other countries, with a trial under way to gauge worker and consumer interest.

The Business Council of Cooperatives and Mutuals has been given a $7m grant from the Albanese government to start a series of support programs in social care focusing on worker- or even client-owned businesses, rather than the current model of either for-profit or non-profit business ownership. Care Together will focus on regional, rural and remote areas where current models are not working.

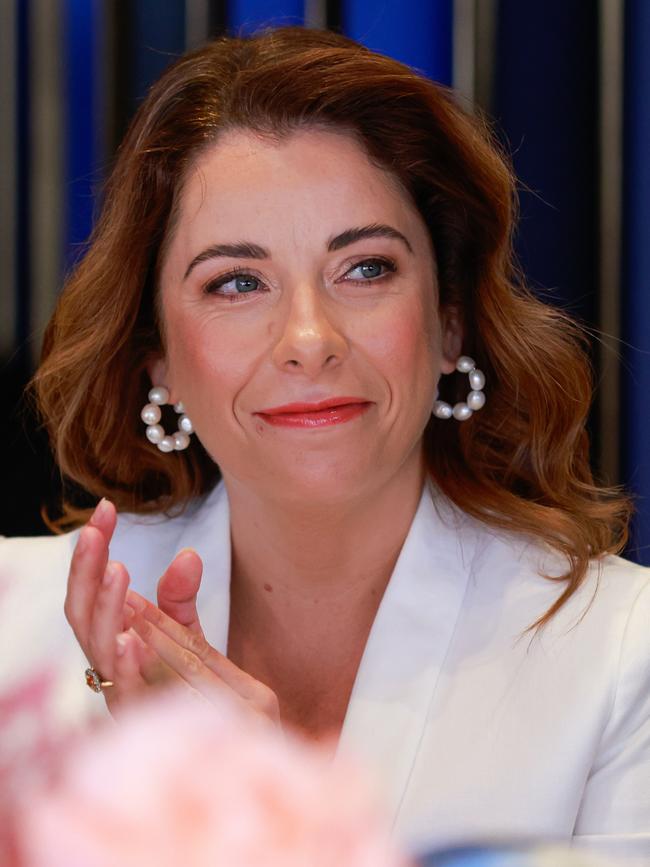

BCCM chief executive Melina Morrison said the funding would “give people a stake” in the delivery of social care, which includes aged and disability care, veterans’ care, Indigenous services, allied health and primary healthcare.

“For instance, the government’s aged-care strategy is built around supporting people to stay in their own homes and out of institutional settings for as long as they are able, but current business models and the funding system doesn’t prioritise that preference,” Ms Morrison said.

“We’re looking to trial a range of innovative ideas to help people achieve this, especially in areas where service provision is in short supply.

“Communities are coming to us desperate for support in this space, we have a pipeline of 20 projects. They are already co-operating, and innovating, across these various care services, but need a structure that supports a sustainable business model,” Ms Morrison said.

Aged Care Minister Anika Wells said the government funded Care Together as part of its push to find “new ideas and innovation in aged care”.

“In some rural and remote areas, and some First Nations communities, current approaches to service delivery simply aren’t working as well as they should,” she said. “Quality, appropriate care and support services should be available to everyone, no matter where they are in Australia.”

Ms Morrison said the current aged and disability care systems were stuck in a rut of rigid conformity, which was leading to supply falling behind demand. And those delivering services had different drivers than quality care.

“We know private equity capital is moving more and more into care around the world, and we do have to be concerned where profit is the motive,” she said. “And some not-for-profits can lack the scale and be built less around their customers and frontline workers than they are around processes and procedures, including funding mechanisms.”

There are co-operative models of social care in Europe, the US, UK and Japan, providing care to millions of people to help them remain in their own home as they age, and which are seeing workers co-owning the service provider, sometimes along with the consumers they support.

“Australia has to ask itself why there are so many jurisdictions where cooperatives are playing such a bigger role in the care economy. In Italy 14,000 cooperatives are providing care to 12 per cent of the population,” Ms Morrison said.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout