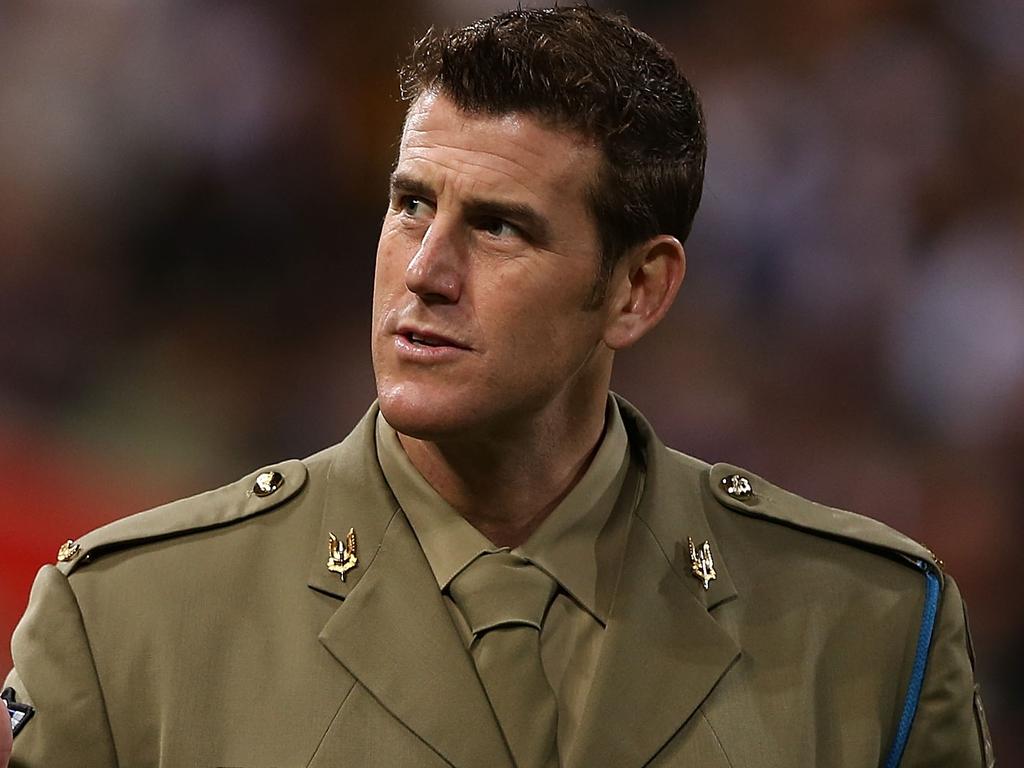

The fateful moment Ben Roberts-Smith went for broke in defamation disaster

The disgraced Victoria Cross recipient rejected an offer from Nine to settle his defamation case just two years ago. His team now faces $40 million in legal fees for persisting.

Ben Roberts-Smith rejected an offer to settle his disastrous defamation claim against Nine that would have allowed him to walk away with only his own costs more than two years ago, with the newspapers anxious to avoid the massive costs of a trial and the trauma for witnesses battling mental health issues.

Mr Roberts-Smith and his ex-boss, media mogul Kerry Stokes, now face a potential legal bill of up to $40m after judge Anthony Besanko ruled that Mr Roberts-Smith had participated in the murder of four unarmed prisoners while serving with the SAS in Afghanistan.

On Friday Mr Roberts-Smith resigned from his position at Mr Stokes’s Seven West Media.

The offer of settlement was made on November 26, 2020, just after the Brereton inquiry revealed credible evidence of war crimes by Australian soldiers in Afghanistan, in a letter sighted by The Weekend Australian from Minter Ellison partner Peter Bartlett, acting for Nine, to defamation specialist Mark O’Brien, acting for Mr Roberts-Smith.

The offer would have allowed Mr Roberts-Smith to walk from the case simply by releasing the newspapers from any liability arising from the articles it had published, with each party bearing its own costs.

Legal experts say Nine now stands a reasonable chance of successfully pursuing Mr Stokes, who bankrolled Mr Roberts-Smith’s case, for costs in the failed defamation trial. But it would depend on the agreement Mr Stokes had with Mr Roberts-Smith, who at the time worked for the media mogul as general manager of the Seven Network in Queensland.

At the point Nine had sent the offer at the end of 2020, it was in a strong position. It had just won access to a “potentially affected persons” notice issued by the Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force against Mr Roberts-Smith, which would ultimately lead Nine to several key witnesses, including one soldier who would give evidence he watched Mr Roberts-Smith execute a prisoner by firing a machinegun into his back. But Nine was conscious of the massive costs certain to result from a prolonged trial. “We wish to make this plain: the respondents, in particular Nick McKenzie and Chris Masters, are eager to see this matter play out at trial,” Mr Bartlett wrote. “The respondents have been successful at every step of this case, and in every interlocutory dispute before the court. This offer is made on a commercial basis. Further as you would no doubt be aware, if your client is charged by the CDPP (Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions) in relation to the crimes before or during the defamation trial, any prospect of your client settling the matter without having to pay our clients’ costs will invariably dissipate.

“Put simply, this offer represents the final opportunity for your client to settle the proceedings without sustaining an immense financial burden.”

Mr Bartlett pointed out the CDPP, the Australian Federal Police and the Office of the Special Investigator would welcome a civil trial at which they could observe Mr Roberts-Smith and his witnesses, “in effect providing the prosecution a dry run at prosecuting your client”.

“We would have thought that your client could materially benefit from focusing on the criminal processes, rather than the costly and heavily involved civil matter, which we plan to ramp in intensity in the coming weeks and months,” Mr Bartlett concludes.

Nearly two weeks later, Mr O’Brien responded on behalf of his client: “Thank you for your judgmental letter of 26 November 2020.” He rejected Nine’s offer.

There was consensus on only one point, Mr O’Brien said: Mr Roberts-Smith, like McKenzie and Masters, was “eager to see this matter play out at trial”. “Our legal team is convinced that the applicant’s evidence will be accepted as credible, corroborated and consistent. If so, he must succeed,” he said.

Mr O’Brien suggested it was Nine’s witnesses, not Mr Roberts-Smith’s, who should be concerned about incriminating themselves in war crimes.

Mr O’Brien concluded his response to Mr Bartlett by questioning his interpretation of the Brereton report.

“In summary, the report found credible information (not evidence) which required further investigation (not that crimes had been committed) and the possibility of credible information to the contrary,” he said. “As this matter progresses to trial, we believe that much of this information will be correctly classified as hearsay, rumour and supposition, not as admissible evidence.”

Asked for comment, a member of the Nine team who did not wish to be identified said the offer had been made in a bid to spare witnesses who had already suffered the trauma of war from the further trauma of enduring a trial.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout