‘Moral revulsion’ in Ben Roberts-Smith case up-ends military code of silence

A Roman contemporary described how “women and children … began to flee in every direction. Caesar sent the cavalry to run them down.” Seeing the carnage, the men of the tribe dropped their weapons and ran.

“A great number of them were killed. The rest threw themselves into the river and perished … Every last one of our men survived, and only a few were wounded.”

It is likely that Caesar had the numbers at home to prevent the senate’s investigating committee from ever being sent, but the episode confirms one of the lessons of Australia’s war in Afghanistan: societies are often uncomfortable with the conduct of wars fought in their name.

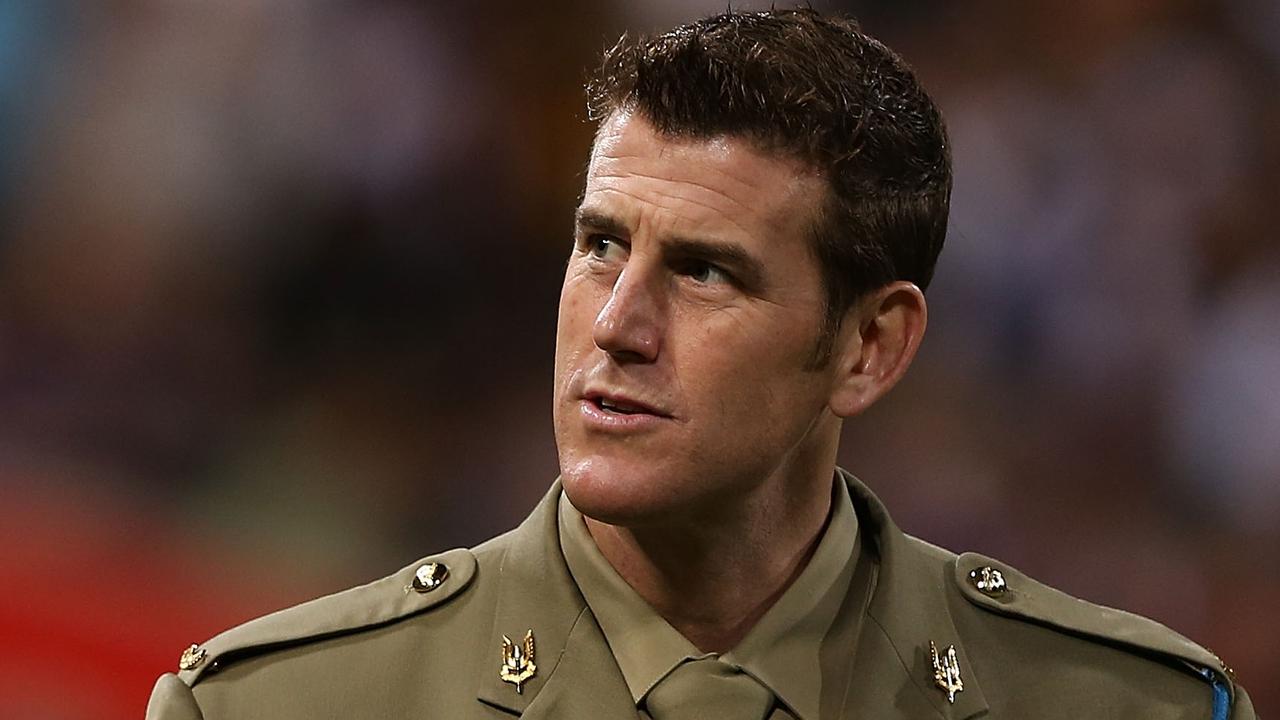

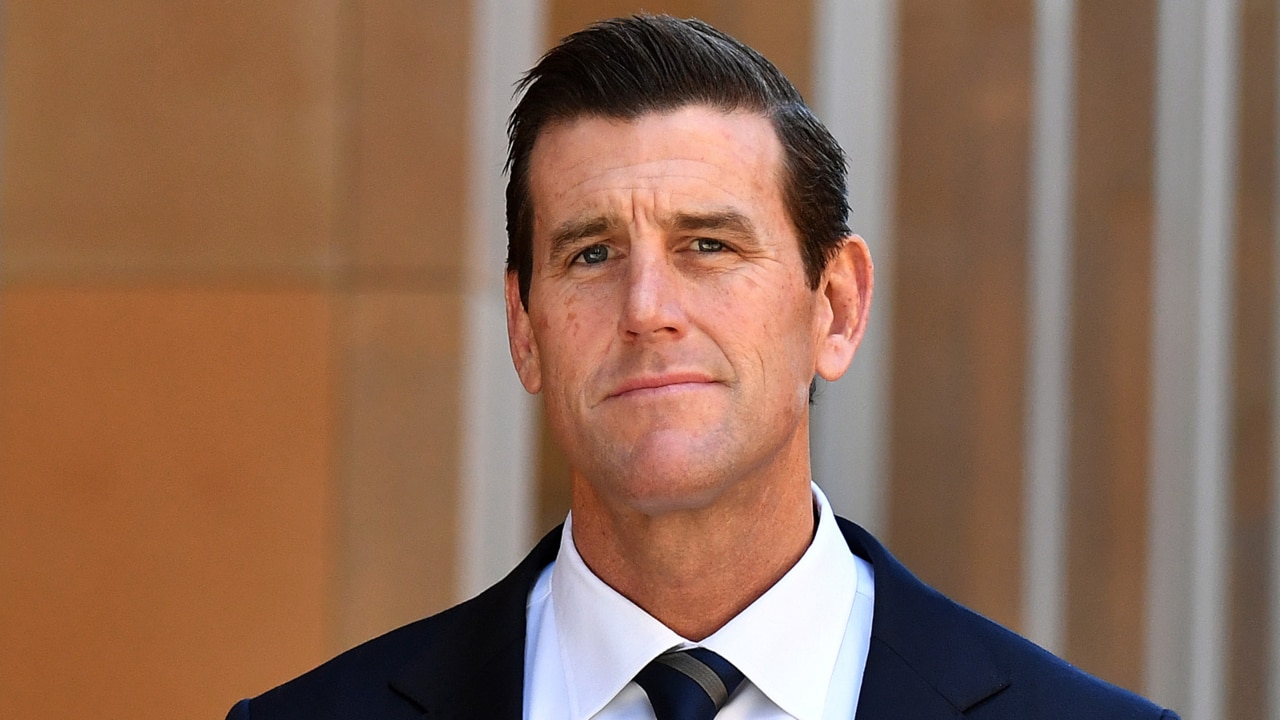

Justice Anthony Besanko’s ruling in the Federal Court that Australia’s most decorated living soldier, Ben Roberts-Smith VC, killed unarmed civilians while serving with the SAS in Afghanistan could lead to Roberts-Smith being formally indicted for murder. The penalty, if he were to be found guilty, would be much worse than the financial and reputational damage he has suffered as a result of his calamitously ill-judged defamation case.

The precedent for such prosecutions has already been set. In March another SAS soldier, Oliver Schulz, was charged with shooting an Afghan father of two in a wheat field in 2012. Footage of the alleged killing was captured on a helmet cam and shown on the ABC’s Four Corners program.

Schulz was the first serving or former Australian Defence Force member to be charged with the war crime of murder under Australian domestic law. He won’t be the last. Schulz faces a life sentence if found guilty.

The facts at the heart of Roberts-Smith’s defamation trial could have been drawn from any insurgent war. In his opening submission Roberts-Smith’s barrister, Bruce McClintock SC, alluded to another Australian accused of committing war crimes against civilians, Lieutenant Harry “Breaker” Morant.

Morant was a member of the Bushveldt Carbineers, the special forces of its day, during the Boer War. He and Lieutenant Peter Handcock were court-martialled for killing 12 prisoners, including a Lutheran missionary – men not unlike Ali Jan, the handcuffed Afghan farmer Roberts-Smith was ruled to have kicked down a cliff and ordered to be shot. Morant and Handcock were found guilty and executed by firing squad.

As in the defamation case brought by Roberts-Smith, evidence against Morant came from fellow soldiers disgusted by what they termed “disgraceful incidents” committed by Morant and other Bushveldt Carbineers, which were said to include the murder of a father and his two young sons, allegedly after the trio were forced to dig their own graves.

Describing Roberts-Smith’s SAS accusers as “bitter people” jealous of his medals, McClintock said Australia “prides itself on its military process” – a term he defined as follows: “It does not mean someone is fit and well trained; shows loyalty to his comrades. It means a person is able to perform in battle and they are able to kill the enemy before they kill him.”

The Australian Army did not accept McClintock’s definition, which flew in the face of its cherished ANZAC mythology. Nor did the parliament or the public. Like the Roman senate, they were discomfited by the perversion of civil laws and values that allowed soldiers to believe they could murder unarmed civilians with impunity.

In 2016 rumours of war crimes allegedly committed by Australian Special Forces in Afghanistan prompted the Chief of Army to refer the matter to the Inspector-General of the Australian Defence Force.

The subsequent inquiry, conducted by NSW Supreme Court judge Paul Brereton, found credible information of war crimes committed by Australian troops in Afghanistan between 2005 and 2016. Echoing the century-old words of “Breaker” Morant’s accusers, the Brereton report called the actions of a number of Australian Special Forces members a “disgraceful and a profound betrayal of the Australian Defence Force’s professional standards and expectations”.

The inquiry uncovered credible information of 23 incidents in which one or more civilians were unlawfully killed “by or at the direction of” Australian Special Forces and which might constitute the war crime of murder. A total of 39 Afghan civilians were found to have been killed in these alleged incidents.

The Brereton report identified 25 serving or former Australian soldiers as alleged perpetrators – as principals or accessories – and recommended that 19 be referred to the Australian Federal Police for investigation and potential prosecution for war crimes.

Nick McKenzie, one of the journalists Roberts-Smith accused of defaming him, joined SAS soldiers in repudiating McClintock’s definition of Australia’s military process.

“There are rules and laws in war,” McKenzie told the ABC’s 7.30 program after the trial ended. “It is unlawful to murder a civilian. It is unlawful to murder a prisoner with his hands bound.” It was, McKenzie said, the “moral revulsion” of Roberts-Smith’s fellow soldiers at witnessing such acts that prompted them to come forward and give evidence against him.

The military code of silence that initially protected Roberts-Smith also protected the American soldiers who murdered more than 300 Vietnamese civilians at the hamlet of My Lai 4 on March 16, 1968. The victims were all women, children and old men.

For a year the soldiers involved in ordering, carrying out and covering up the My Lai 4 raid kept their dirty secret. The massacre came to light only when another American soldier, Ronald Ridenhour, who had heard about the raid but not taken part in it, wrote to the White House, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and dozens of congressmen describing the murders at My Lai.

An army investigation uncovered detailed information about the atrocities at My Lai 4 and at nearby hamlets on the same day, but only one soldier was convicted of taking part in the murders. The only senior officer to stand trial for the cover-up was acquitted.

Vietnam was a different kind of war to the two world wars and the Korean War, all of which were largely characterised by conventional armies fighting each other in pitched battles. The Vietnam War, like the Boer War 70 years earlier, was fought by regular soldiers and insurgents who hid among a sympathetic civilian population. The war in Afghanistan followed the same pattern. In such wars the distinction between civilians and combatants can become fatally blurred in the minds of soldiers.

In 2010 the US Public Broadcasting Service documentary series American Experience featured an episode about My Lai. An American soldier who had participated in the massacre told the program-makers: “A lot of people talk about My Lai, and they say, ‘Well, you know, yeah, but you can’t follow an illegal order.’ Trust me. There is no such thing. Not in the military. If I go into a combat situation and I tell them, ‘No, I’m not going. I’m not going to do that. I’m not going to follow that order’, well, they’d put me up against the wall and shoot me.”

Evidence given by witnesses in the Roberts-Smith defamation trial showed that Australian soldiers in Afghanistan could be bullied or intimidated into following illegal orders. That their comrades were not prepared to stay silent demonstrated, according to McKenzie, that “the moral heart of the SAS is solid”.

The next few months may put that statement to the test.

After one of the more shocking war crimes committed by Julius Caesar’s legions in Gaul, the Roman senate appointed a committee to investigate. The incident that horrified the senate was the massacre of a German tribe Caesar accused of violating a truce.