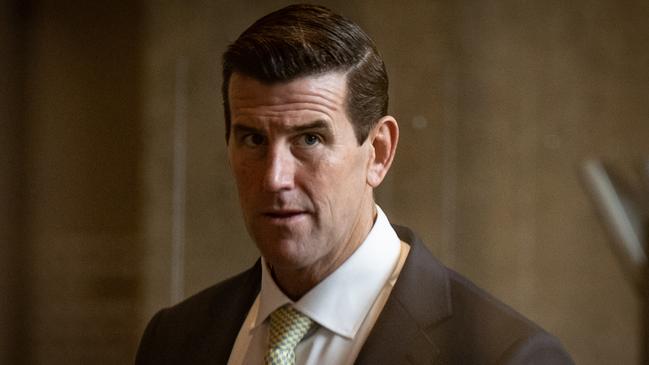

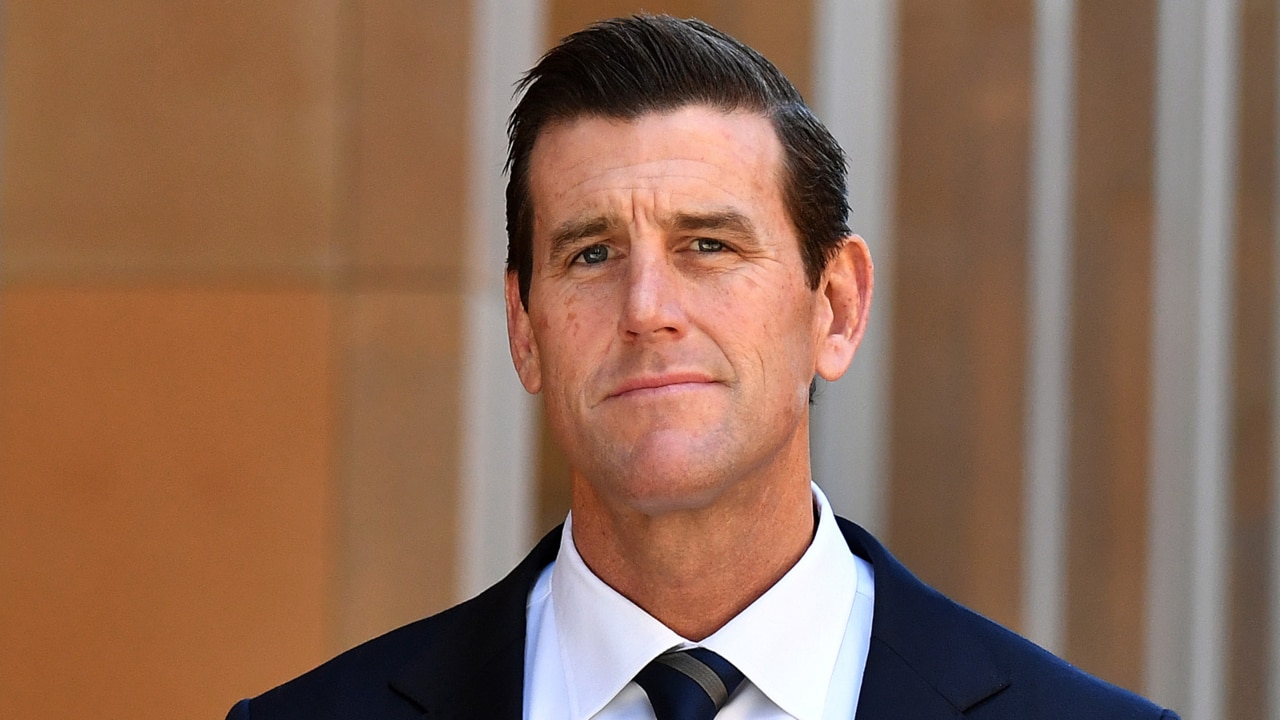

Ben Roberts-Smith brought war to the courthouse as his legal team fought Nine and each other

Behind the scenes of most court cases there’s a certain camaraderie between opposing legal teams. Ben Roberts-Smith’s defamation action against Nine was not one of them.

Behind the scenes of most court cases there’s a certain camaraderie between opposing legal teams.

Ben Robert-Smith’s defamation action against the Nine newspapers was not one of those cases.

“There was no bonhomie,” says one participant with calculated understatement. “This was total war.”

From the moment the famed Victoria Cross recipient pushed the button to start proceedings there was no question this would be the biggest, most expensive defamation battle in Australian history.

But it would not just be the reputations of the war hero and the journalists on the line.

Each side was assembling legal teams from among the biggest names in the profession.

The case would be fought with an intensity few of the players had ever experienced.

There would be claims of dirty tactics, allegations of backroom deals and interference with witnesses, even purported attempts by the newspapers to intimidate the soldier’s lawyers via their gossip columns.

A female lawyer would be falsely accused of having had a sexual relationship with Roberts-Smith, her client, an allegation that would fuel ongoing bad blood between the two sides.

There was never any question which side had the heaviest hitters.

Roberts-Smith’s team – bankrolled by billionaire media mogul Kerry Stokes - was fronted by two of Sydney’s most expensive defamation silks.

Bruce McClintock SC, a bulldog of a man, gruff and combative, was taking on one last case before retirement and determined to go out with a win that befitted a hugely successful career at the Bar.

Arthur Moses SC, who has starred in dozens of high profile legal battles and is a specialist in military law, is renowned for his aggressive approach to cross examination.

When Moses asked one SAS witness about another soldier who had given evidence earlier, the witness reported: “He said you went at him like a rabid dog.”

Backing the pair as they jostled for top position in Team BRS was defamation stalwart Mark O’Brien, with Seven Network executive Bruce McWilliam rarely far from the court, albeit constantly scrolling his phone.

It wasn’t the first time some of the team had gone up against Nine over a Nick McKenzie story. When businessman Chau Chak Wing sued over a story written by the reporter, the Chinese billionaire had both Mark O’Brien and Bruce McClintock in his corner – and won $590,000 in damages.

All sides deny the Roberts-Smith case was a grudge match.

Nine’s legal team was helmed in court first by Sandy Dawson SC, and when he became ill and had to retire from the case, by Nicholas Owens SC, backed by lead solicitor Peter Bartlett. In the wings were defamation specialist Lyndelle Barnett and former Balkans war crimes prosecutor Chris Mitchell, whose eye for detail helped comb thousands of military records and photos for clues.

Each team had a human encyclopaedia of the case.

In the Roberts-Smith camp it was Monica Allen, a tenacious lawyer utterly convinced of Roberts-Smiths’ innocence who travelled around the world collecting testimony from the former soldier’s scattered comrades.

In the Nine camp, it was Dean Levitan, a powerhouse young lawyer who lived the saga 24/7 for three years.

Roberts-Smith ‘acted provocatively’

From the outset, the Nine team thought Roberts-Smith himself was acting provocatively.

At the trial he would position himself every day in the back corner of the court next to the window, the first person any witness saw as they walked in, glaring at them, according to the Nine camp.

“Roberts-Smith would absolutely give them filthy eye as they walk through and I just thought, jeez, this is real intimidation, and it was a real sense of hostility in the court,” said one member of the team.

The first big win for the Nine side came with a master stroke from barrister Sandy Dawson, after the team learned Roberts-Smith had been served by the Inspector General of the Australian Defence Force with a ‘Potentially Affected Persons’ notice, where a suspect is informed of likely findings against them.

The IGADF had refused to give up the document but Dawson reasoned Roberts-Smith himself had been sent it, so why not subpoena him for it?

After a long, sidebar legal battle, Roberts-Smith was ordered in November 2020 to hand over the PAP notice – heavily redacted, but a gold mine.

A member of the Nine team recalls: “Once we got that, we identified witnesses who we had not identified before and so we could add witnesses to our case.”

One of those was a soldier known only as Person 41, who would go on to give perhaps the most crucial eyewitness evidence in the case: that he watched Roberts-Smith frogmarch an Afghan man found in a tunnel at the compound known as Whiskey 108 and fire a machinegun into his back.

The win on the PAP notice shifted the momentum to Nine’s corner.

But the legal costs were already mounting and would be massive if the case went to a full trial.

Nine had already made two offers to settle, first in June 2019, then again in March 2020.

In December 2020, they tried again.

The offer would allow Roberts-Smith to walk away from the case with only his own costs to pay.

The letter, to Mark O’Brien, made it clear Nick McKenzie and Chris Masters would be happy to see Roberts-Smith in court, but the offer was made on a commercial basis: “the final opportunity for your client to settle the proceedings without sustaining an immense financial burden.”

The response from O’Brien was brutally blunt: the only point on which there was agreement was that Roberts-Smith, like the journalists, was “eager to see this matter play out at trial.”

The offer was rejected.

The Nine team thought it was a sneering response.

The atmosphere between the legal teams became steadily darker over time, intensified by the drawn-out, Covid-prolonged process and the deep belief of each side in the justice of its own case.

The Nine team regarded Arthur Moses in particular as unnecessarily rude to witnesses.

Even Justice Besanko found it too much at one point, sternly telling the silk: “I won’t tolerate raising the voice to the extent you did in this court, Mr Moses.”

A month before the trial began, Person 4 – the other most important witness in the case – said he had never spoken to Nine and had no idea they were relying on his evidence. That was despite the publishing giant having two years before filed an outline of his expected evidence in which they claimed the ex-soldier would testify he had been ordered by Roberts-Smith to help murder Ali Jan, the Afghan farmer kicked off a cliff in the village of Darwan.

Arthur Moses called it an “extraordinary” revelation.

“We’re not sure where they got that from, whether it was made up by them, whether they were sold a pup by somebody or whether they received information unlawfully,” Mr Moses said.

Team BRS was, quite reasonably, demanding the judge draw a line in the sand: Your Honour, there’s got to be a cut-off day when we know these witnesses are either coming or not coming.

Justice Besanko agreed, issuing a deadline: any witness who’s not going to come needs to put an application on to the court.

No one did, or at least, none of the key witnesses.

Cancer diagnosis

The only moment in the trial when anything like a truce was declared came when the highly respected Sandy Dawson was diagnosed with brain cancer and forced to withdraw from the case.

Both sides were devastated by the loss of the witty and much-loved defamation barrister, who died in November last year at age 50.

Despite his illness, Dawson had worked tirelessly to hand over the reins in the case with meticulous detail.

His successor, Nicholas Owens, was known as a brilliant commercial silk. The suggestion that he should replace Dawson was met with alarm among some members of the Nine team. Owens had never done a defamation case or a criminal case and this was about the most serious collision of those two fields of law anyone had seen.

Some in the team wanted to meet Roberts-Smith’s attack-dogs head-on with one of their own - someone like Mark Tedeschi, the feared former NSW senior prosecutor now defending ACT prosecutor Shane Drumgold at the Sofronoff inquiry into his conduct of the Bruce Lehrmann trial.

But cooler heads prevailed and Owens came on board.

The barrister has a restrained, gentlemanly courtroom manner.

On the first day he cross-examined Roberts-Smith this newspaper described his style as “grindingly slow” and wondered if there was method behind the drabness.

There was. He quickly won his own side over.

“Owens was an absolute blessing, just brilliant” says one member of the team.

Besanko in any case was not the kind of judge who cared for theatrics in his court.

In the absence of a jury, the quietly methodical Owens held his own against the showmanship of McClintock and Moses.

But in the early days of the trial, the Nine team were worried.

The Roberts-Smith side arrived in court oozing confidence. They looked like winners.

McClintock skilfully laid the groundwork for a case in which the fog of war obscured both moral certainty on the battlefield and memories of those events a decade later.

He opened the case by quoting Winston Churchill: “We sleep safely at night because rough men stand ready to visit violence on those who would harm us.”

The first witness up was Ben Roberts-Smith himself, and he was impressive. Even the Nine crew had to admit it. Poised, articulate, with clear recollection of events on the battlefield a decade earlier.

Behind the scenes each side was still madly scrambling to assemble witnesses.

Roberts-Smith had a trusted core of half a dozen former comrades-in-arms whose patent disgust at having to appear in court was outweighed only by their apparent outrage at the accusations levelled against him.

Nine had a long list of witnesses it desperately needed, none of whom wanted to appear. Many could legitimately play the mental health card if they chose.

The dynamics of the trial shifted again, almost imperceptibly.

There were signs of tension between Arthur Moses and Roberts-Smith, for reasons no one could discern.

There were signs of tension between Arthur Moses and Bruce McClintock, for reasons everyone could discern: Moses was in a new relationship with former NSW premier Gladys Berejiklian, whom he’d represented at an Independent Commission Against Corruption inquiry into her relationship with disgraced ex-MP Daryl Maguire.

McClintock was the Inspector of ICAC. In October 2021 he ruled that ICAC was perfectly justified in launching its public inquiry into Berejiklian. Gladys and her new “Boo” were less than impressed.

“You could have cut the air at the bar table with a knife!” said one observer of the trial.

But Nine had its own problems.

“We never knew whether witnesses would come even though they were subpoenaed, because who knows?” one player said. “They’re they’ve all got their trauma, none of them owe us.”

It’s a measure of the gulf between the two sides that each felt aggrieved by Justice Besanko’s grant of immunity certificates to several soldiers who otherwise might not have given evidence, for fear of implicating themselves in war crimes.

The newspaper’s lawyers were angry that a key witness, Person 4, got a certificate that allowed him to testify about what he saw in the village of Darwan – Roberts-Smith kicking Ali Jan off the cliff – but not about his own alleged role in committing a murder at Whiskey 108 alongside Roberts-Smith.

Roberts-Smith’s lawyers were angry because Person 4 had managed, in their words, “to do a deal with Nine” so he didn’t have to give evidence about his own war crimes but was allowed to give evidence about those alleged against their client.

Reporter’s tweets

McKenzie’s prolific and borderline contempt-of-court tweeting (“RS case an unprecedented attack on vital war crimes reporting”) throughout the case annoyed Roberts-Smith’s legal team mightily but they reasoned trying to shut it down would have given him more ammunition.

But that paled in comparison to the team’s anger when the Nine-owned Australian Financial Review published a gossip piece saying the soldier was seen jogging near the Potts Point apartment where lawyer Monica Allen lived.

Justice Robert Bromwich, who was dealing with a separate case brought by Roberts-Smith against his ex-wife Emma Roberts, demanded to know whether the pair were in “a personal relationship”, saying that if correct it “raised a question of utmost good faith.”

Clearly irked, the judge told the soldier’s legal team he wanted an explanation of this “potentially embarrassing situation”.

“I’m surprised this wasn’t raised with me directly quite frankly. I’m surprised it was left for me to raise it,” he said.

The relationship between the pair had been the subject of innuendo for some time, after they were photographed holding hands together in Brisbane the year before.

But Moses had had enough.

“Female lawyers have enough to deal with in this profession without these aspersions being put against them,” the barrister said angrily.

Moses returned to court with a formal denial that any personal relationship existed and claimed Nine was attacking Roberts-Smith’s lawyers in its coverage.

“That may have the tendency of seeking to intimidate or threaten those lawyers, that may itself constitute a contempt of court,” he told Justice Bromwich.

The barrister noted that Bromwich’s comments had generated a wave of media coverage - including by Nine’s newspapers.

Dismissal of Ben Roberts-Smith case is a big win for Nine over Kerry Stokes-controlled Seven

“This is how it apparently works. Nine makes an insinuation in a gossip column. It’s referred to in open court in another matter … and then becomes a lead story on their homepage,” he said.

Nine denied any articles intimidated or threatened lawyers and said none constituted contempt of court.

On Thursday afternoon, almost a year after the trial ended, Justice Besanko sat down in Court 1 to deliver his findings.

Australia’s most decorated war hero had murdered innocent civilians in Afghanistan.

It was not unexpected. Roberts-Smith hadn’t even bothered to turn up to court, retreating to the relative anonymity of a resort hotel in Bali.

McKenzie let out a sigh of relief as Besanko’s words sunk in and gave Masters a quick hug.

But when the court finally adjourned there were none of the customary handshakes between opposing legal teams.

The case had ended as frostily as it had begun.