Struggling students ‘left to fail’ at school, new literacy report reveals

‘GPs see them coming through their doors with their sad little faces and slumped shoulders.’ A concerned doctor spells out the mental health impacts of schools’ failure to teach all children to read.

Frustrated parents of semiliterate children are spending tens of thousands of dollars a year on remedial tutoring and speech pathology for children who are not taught to read properly at school.

The extent of literacy problems is spelled out in a new Equity Economics report commissioned by Code REaD Dyslexia Network, chaired by Adelaide GP Sandra Marshall, who co-founded the advocacy group after her dyslexic son struggled to read in primary school.

Dr Marshall said speech pathologists should be sent into schools to help diagnose dyslexia, and teachers should focus on teaching phonics to ensure all children learn to read properly.

“As a GP I can confidently say that if the lack of standards of evidence in education were used in health, we’d be sued for malpractice,’’ she said.

“Teachers aren’t being trained about this at university, and there is a lack of screening and early intervention.

“It’s a massive problem and children are just being left to fail.

“GPs see them coming through their doors with their sad little faces and slumped shoulders.’’

Dr Marshall said parents were asking her to write mental health plans for children who were feeling anxious or depressed because they had never been taught to read properly.

“They just hate school, they’re failing at school and feel awful about themselves,’’ she said.

“They’re getting one out of 10 marks in their spelling test on Friday, and when school starts on Monday they’re feeling sick, with headaches or stomach pain, and they’re having tantrums at the school gate – it’s really distressing.

“The schools just expect parents will find somebody to help the child, and fund it, but that completely disadvantages the normal Australian.’’

Melanie Eglinton, a Brisbane mother of two boys diagnosed with dyslexia, said she had spent $20,000 a year for speech therapy, psychology and phonics-based tutoring for her sons.

“I feel for kids whose families don’t have the resources,’’ she said. “Teaching reading through phonics would have changed our lives – financially too.’’

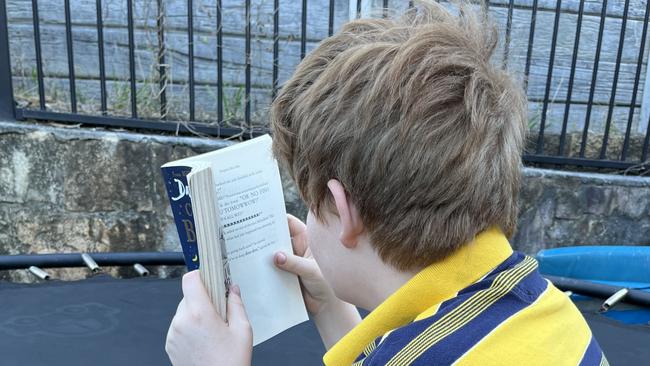

Ms Eglinton said she noticed her older son, now 17, had struggled to read when he started school.

“I was just told, ‘He’s a boy and he’ll be fine’,’’ she said.

“His report cards said he was passing but at home I could see he was struggling.’’

An educational psychologist diagnosed her son with dyslexia “but the school did nothing’’.

Ms Eglinton said the Catholic primary school had based its reading instruction on children guessing words from pictures and memorising lists of words, instead of sounding them out through phonics-based teaching.

The Equity Economics report shows South Australia and NSW are the only states to have mandated the “phonics check’’ of students’ ability to recognise sounds of the alphabet in simple words at the start of year 1.

Tasmania recently announced it would adopt the check.

Equity Economics calls on all governments to mandate the year 1 phonics check, screen students for reading problems “all the way from preschool to entry to high school’’, and provide catch-up tutoring for struggling students.

The new national curriculum, released last year, includes phonics-based teaching of reading but no state or territory has begun using the new syllabus.

Education ministers agreed in June to force universities to include explicit teaching of phonics-based reading in all teaching degrees by 2025.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout