How is it that after four years at university, graduates can’t teach?

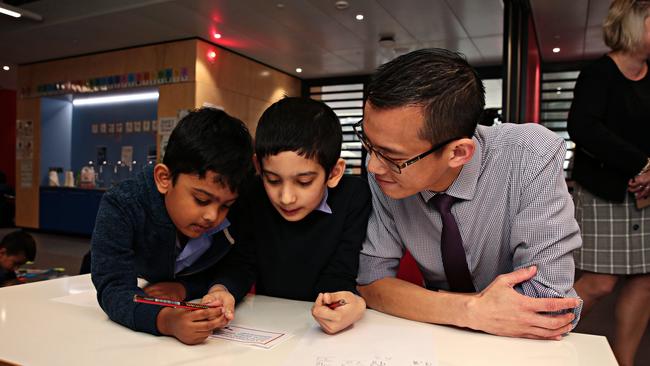

Master maths teacher Eddie Woo struggled during his first year fronting a classroom. If he had a magic wand to improve the education system, this is what he’d change.

Thrown in the deep end, master maths teacher Eddie Woo struggled during his first year fronting a classroom of teenagers.

“I spent a sum total of two months, during all my years at university, in a school,” he says of his four-year teaching degree.

“Contrast that to Singapore where, in order to be qualified as a teacher, prospective teachers have to spend 12 months in a school, earning a stipend as teacher aides, and at the end of 12 months the school has to ratify or deny entry to the university system.”

Woo now divides his time teaching at Cherrybrook Technology High School in Sydney and mentoring other mathematics teachers for the NSW Education Department. If he had a magic wand to improve the education system, he says, he would reform initial teacher education, known as ITE, so that university students spend more time in school classrooms before they graduate.

Woo’s wisdom has gained traction after the nation’s education ministers gave the nod to a Universities Australia plan for hybrid apprenticeship-degrees, so ITE students can combine theoretical study with more practical experience as part-time teaching assistants, paid to learn as they earn.

“We can help create a degree apprenticeship system where, like any other apprenticeship, student teachers have the opportunity to do more training in schools with a job secured at the end of it,” Universities Australia chief executive Catriona Jackson declared at the end of the ministerial summit last week. “We can also expand and scale up programs to get student teachers into classrooms sooner, and for longer.”

The modern model harks back to the in-service training at teachers colleges before they were assimilated into universities in the 1980s and ’90s. What once was a two-year teaching qualification based on practical experience has now become a four-year degree focused on educational theory.

The shift from a training-based model to university degrees has not necessarily translated to more competent and confident teachers. Worryingly, despite 13 years at school and four years at university, one in 10 ITE undergraduates is failing to pass the mandatory literacy and numeracy test that is a prerequisite of graduating. Financial incentives are failing to lure school-leavers into a teaching career, even though $75,000 starting salaries are higher than for doctors, nurses, engineers or lawyers beginning their first job. The former Coalition government boosted taxpayer subsidies for education degrees nearly 50 per cent, so students have to pay just $14,800 for a four-year degree.

Despite this, applications to study education at university are plummeting and entry standards falling. Last year 16,890 students were accepted into education degrees – down from 17,667 a decade earlier. Half will fail to finish their course; the 50 per cent dropout rate for teaching is far higher than the 30 per cent average for other degrees.

The alarming attrition rate is of concern to federal Education Minister Jason Clare, who has flagged performance-based funding for universities so federally subsidised teaching places are funnelled to universities with the highest course quality and completion rates.

Entry standards to teaching are falling, too: the minimum Australian Tertiary Admission Rank entry scores for a bachelor degree in education last year ranged from 39 at the University of Tasmania to 51 at RMIT University, and 83 at the University of New England. The raw entry ranks, which can be padded later with bonus entry points for disadvantage, are published on the federally funded Course Seeker website using data supplied by universities. They show that the academic ability of some student teachers is in the lowest cohort of high school graduates.

Education ministers agree that some universities are failing to give teachers the skills they need for high-quality teaching.

A review of ITE, commissioned by former Coalition education minister Alan Tudge and adopted by his Labor successor Clare, has identified reading instruction – the foundation of education – as one of the failings of university training.

“Consultation with ITE graduates and employers of teachers nationwide revealed a consistent, shared concern: far too many graduates are leaving university underprepared to teach children how to read,’’ the review concluded. “Many ITE graduates feel confused about how to approach reading instruction and are unaware of the reason they should use particular strategies over others. Experienced teachers are spending time developing underprepared early career teachers in evidence-based reading instruction.’’

To ensure universities stay in touch with modern classroom requirements, the review recommended they be required to publicly report the proportion of academic staff in ITE who have “substantial recent experience in schools or childcare centres”.

Clare has shared this concern, questioning why just 12 per cent of the content of an education degree deals with teaching literacy.

Australia’s biggest employer of teachers, the NSW Education Department, has told the ongoing NSW parliamentary inquiry into teacher shortages that ITE graduates need better training in classroom management and in teaching students with disability, gifted students and students from Indigenous or migrant backgrounds.

How is it that, after four years at university learning to be a teacher, some new graduates can’t cope with disruptive classrooms or teach children how to read and write? Perhaps universities would do well to devote more time instructing would-be teachers in the 3Rs of reading, writing and arithmetic, and less time on gender theory, cultural identities and sociological perspectives.

At the University of Sydney, education students can study a unit on “sociological perspectives in education’’.

“Using a sociological lens it explores key issues concerning difference and inequality in education-including ‘race’, social class, religion, gender, sexuality, cultural diversity, and indigeneity,’’ the subject outline states.

“It provides a critical analysis of the teaching profession and how issues of power, privilege, social justice and globalisation impact education and educational policy.’’

In an eye-rolling example of educational jargon, a unit called Research with Young Children explains: “Contemporary educational paradigms and pedagogies advocate theories of learning that conceptualise education as a process of participatory research, where children are active agents and teachers are facilitators and co-constructers of meaning.’’

The fact so many Australian children are educationally handicapped by poor literacy skills must be a priority for the education system and therefore for teacher training.

By year 9, one in every 10 girls and one in five boys failed to meet the minimum standard in writing by the age of 15, based on the most recent NAPLAN testing. Essentially, this means they cannot punctuate sentences, spell most simple and common words, or write a story in paragraphs.

At the University of Melbourne, postgraduate students paying $63,500 for a master of teaching in early childhood – to teach preschool and kindergarten children – must write a 3500-word essay on the “professional roles and responsibilities of early childhood teachers”.

Another task is to “critically examine either a policy or curriculum document with regards to how it informs constructions of childhood”, in a 1500-word “document analysis”.

Education and Society is the first unit aspiring teachers will study in a Queensland University of Technology education degree. “In this unit, you will develop reflective and critical understandings of the socially, culturally and historically constructed nature of education and care, and be able to identify the social identities and structures influencing contemporary early childhood, primary, middle and senior school contexts,” the course overview states.

The NSW Council of Deans of Education – representing universities’ education faculties – has revealed a 29 per cent slump in enrolments in teaching degrees in NSW across the five years from 2014 to 2019.

“The situation is much worse when it comes to teaching as a top choice for students,’’ it told the NSW teaching inquiry. “In NSW from 2013 to 2021, applications from students who put teaching down as their first preference – in other words, the students who most want to become teachers – dropped by over half. We need to change the public perception about the teaching profession.’’

Education ministers want to recruit more career-changers to teaching, so that IT experts, lawyers, engineers, medicos and accountants with a university degree can be fast-tracked into classrooms to plug the shortage of teachers with expertise in specialist subjects. Career-changers must complete a two-year master degree in education to qualify as a teacher, which Clare concedes is a disincentive for midlife professionals with a mortgage to quit work while they study full time for two years.

The Australian Education Union will fight moves to halve the time needed for a master degree, to one year.

“Fast-tracking teaching qualifications does not work in the long term,” AEU president Correna Haythorpe told Inquirer. “Current workforce shortages are not a valid excuse to compromise the time required by ITE students to develop pedagogy and skills in universities, and put unqualified people in classrooms.”

The Teachers and Teaching Research Centre at the University of Newcastle argues that students “deserve qualified, well-prepared teachers, not any adult willing to be in a school”.

“The main message – that any warm body will do – significantly undermines efforts to raise the status of the teaching profession, which is critical in attraction to and retention in the workforce,” says the centre’s director, laureate professor Jenny Gore.

Education ministers resolved last week to prepare a national teacher workforce “action plan” by year’s end, for “immediate action”. They appointed University of Sydney vice-chancellor Mark Scott – a former NSW Education Department secretary – to look at ways to “strengthen the link between performance and funding of ITE”.

Ministers also agreed to change the practicum component so student teachers are placed in classrooms at the start, rather than the end, of their degree.

“States and territories will work with the Australian government on a plan to ensure all first-year students have an opportunity to undertake high-quality placements in schools, undergo initial assessment of their literacy and numeracy skills in their first year, and ensure they can receive targeted support if they need it,” they stated in a communique after the meeting in Canberra last week.

The St Philip’s Teaching School, based in the Hunter Valley in NSW, is already transforming teacher training through an apprenticeship model in partnership with Alphacrucis University College. The school sponsors university students from the local region and employs them as teacher’s aides one day a week, mentored by principals and classroom teachers, while they study an education degree. Trainees spend 350 days in a classroom before graduation – five times longer than the practicum in a typical university degree.

Peter Rose, 29, is in his final year of his teaching degree, combining university study with part-time work as a “trainee teacher”.

“I’ve been exposed to classrooms from the first day of my degree,’’ he says. “Within two or three months I was running my own lessons, supervised by my mentor teacher.’’

One of the first graduates of the innovative program was Bethan Knaus, 31, who was working as a youth support worker before retraining as a teacher.

“Other people are waiting two or three years before they get to stand in front of students, and then it’s only for a short period of time,” she says. “In the university degree, we learn a lot about pedagogy and engaging young learners, and I can practically implement strategies rather than just have them on paper. Having a mentor teacher guiding you, you’re never going to be thrown to the wolves.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout