Warning on Reserve Bank power over interest rates

The Reserve Bank risks ‘losing control of the cash rate’ under the ‘radical’ proposal to give external experts more votes on monetary policy than central bank officials.

The Reserve Bank risks “losing control of the cash rate” under the RBA review panel’s “radical” proposal to have voting external experts outnumber central bank officials on a new board that will set the country’s monetary policy, leading economists warn.

As part of what will be the biggest overhaul of the independent RBA in three decades, responsibility for interest rates would be handed to a new monetary policy board of nine, which would include six external expert members who “collectively, have a deep understanding of areas such as open-economy macroeconomics, the financial system, labour markets and the supply side of the economy”.

A more formalised voting system, combined with the review’s emphasis on these external members challenging the house view, represented a major shift from the consensus approach currently practised by the board, economists said. The proposed model made it more likely to lead to the apparently perverse outcome where interest rate decisions were not backed by the Reserve Bank governor or his staff.

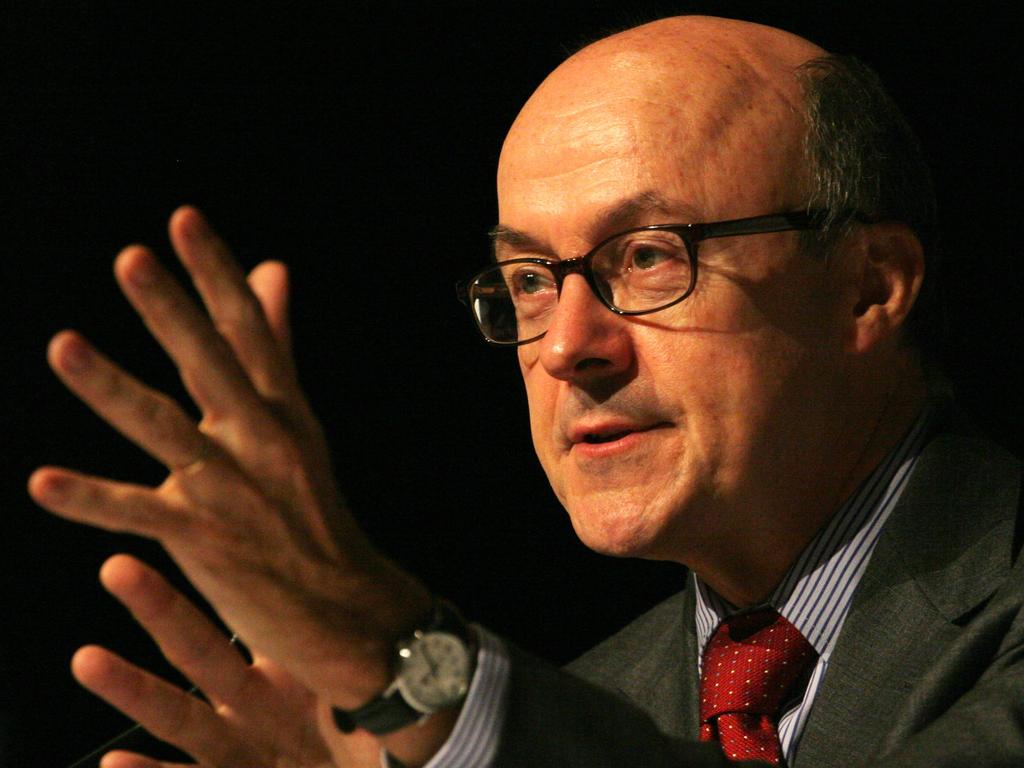

Ahead of what could be RBA governor Philip Lowe’s final appearance at Senate estimates on Wednesday, CBA head of Australian economics Gareth Aird said “it is possible that the RBA at times under the new structure does not control the cash rate target or monetary policy”.

The government believes the proposed monetary policy committee membership is uncontroversial, as it replicates that of the current board.

While the ratio of external to internal board members would technically remain the same, Mr Aird said: “I think you are handing more power to the external members to the extent that everyone is explicitly voting.

“The RBA could be outvoted by the other members of the board. That is different to other central banks where the majority of board members are from the central bank. The new proposed structure of the board is different from what is generally considered best practice.”

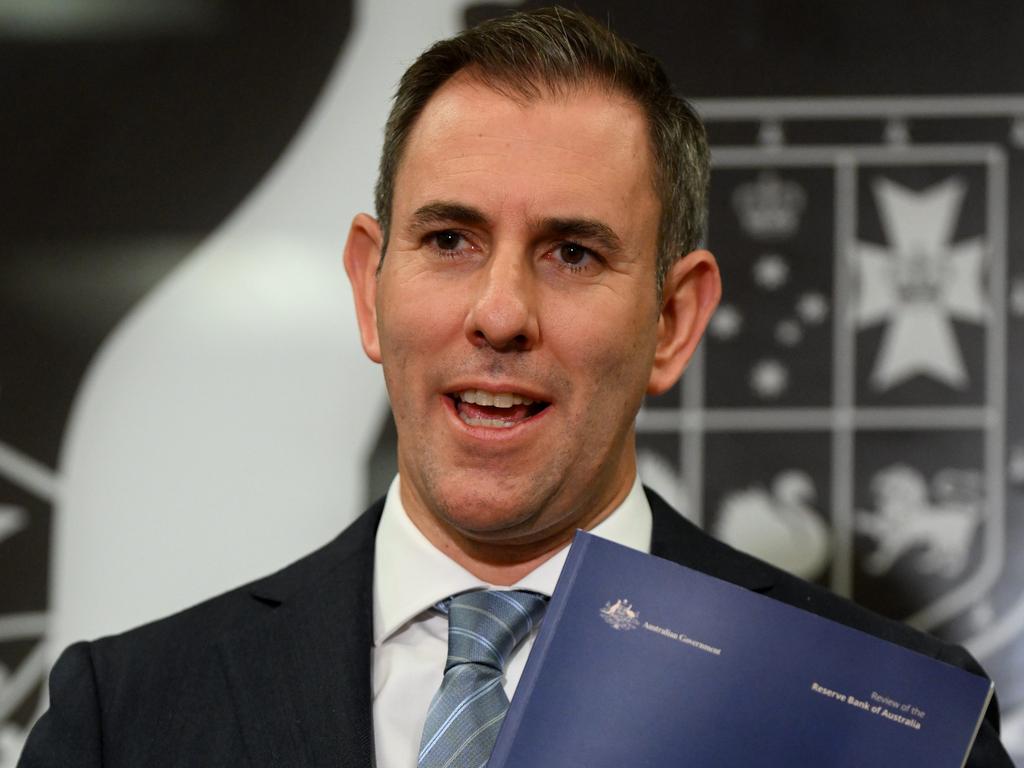

After The Australian put these concerns to Jim Chalmers, a spokesman for the Treasurer responded by saying: “The government agrees in‑principle with all the review’s recommendations and is working with the RBA, the parliament and other stakeholders to implement them.”

The new rate-setting board would be chaired by the RBA governor, and include his or her deputy and the Treasury secretary. A separate governance board would be responsible for the day-to-day management of the central bank.

Under the proposed changes, each member would be required to make a formal vote on whether to hold, hike or cut rates, and those unattributed votes for the first time would be published in the accompanying statement.

Every meeting – which under the proposed changes would take place every six weeks rather than every month – would be followed by a press conference.

Earlier this month, Westpac chief economist Bill Evans described the proposed composition of the monetary policy board as a “much more radical model than we see in other major central banks”.

Central bank representatives outnumber external members on the monetary policy-setting boards in the United States, Canada, England and New Zealand. The notable exception is in Europe, where the European Central Bank governing council includes representatives from each of the 20 countries that use the euro. Speaking to The Australian from New York, Mr Evans said his “concern is that new members of (the monetary policy) board are appointed for their monetary policy expertise implying a responsibility to challenge the recommendations of the governor”.

“Other central banks have appointed expert policy outsiders, but not giving them the majority over the bank representatives. With a clear majority of seven to two, the risk of a dysfunctional decision process where members do not have the insights afforded to bank representatives looms large,” he said.

“That is particularly exacerbated by having nine members of the board with a publicly disclosed vote. (The) previous model was not to disclose the vote and appoint board members with excellent commercial expertise (and) wide experience without an obligation to challenge the bank’s views.”

The Albanese government has given “in-principle” support to all the review’s recommendations, and the creation of a new board responsible for rates decisions will require legislation to pass through parliament.

Opposition Treasury spokesman Angus Taylor has offered bipartisan support to implement the review’s recommendations, but said it was crucial that the non-executive board members be appointed in the most transparent fashion possible.

He said he was already “disappointed” that the recent appointment by Dr Chalmers of two new board members failed to reach that higher bar. “It is important transition arrangements including the appointment of new board members be handled in a bipartisan manner to preserve confidence in the bank,” Mr Taylor told The Australian.

Dr Chalmers last month announced ex-Fair Work Commission president Iain Ross and corporate director Elana Rubin to the RBA board – two highly qualified individuals with union roots.

The RBA review panel report – titled An RBA Fit For The Future – found that while they were “outstanding leaders in their fields … the economic expertise of the Reserve Bank board’s external members is lower than for comparable central banks”.

The report said current and former external board members described their roles “in various ways, ranging from providing real-time feedback on the economy, to an informed second opinion, to a ‘pub test’ of how decisions might be understood by the public”.

NAB’s Alan Oster said he was not worried about the proposed policy board structure, but also emphasised how important it was to appoint the right external candidates.

“I don’t have a problem with it (the proposed monetary policy board). It’s up to the judgment of those external members and they are going to be given a lot of detail by the RBA,” Mr Oster said.

“They just have to be careful who they choose as the six experts. I think they should bring in some sort of economic expertise, in academia but also some in the financial markets as well,” he said.

“You don’t just want pointed heads (who) don’t know which way is up.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout