Victoria’s debt burden to hit $190bn, Treasurer Tim Pallas reveals in state budget

Victorians face an interest bill of $26m a day to service their debt, despite spending cuts and delays to major projects announced in Tuesday’s state budget.

Victorians will face an interest bill of close to $26m a day to service state debt of almost $190bn by 2027-28, as the Allan government sticks with its controversial Suburban Rail Loop, despite imposing heavy spending cuts and delaying the rollout of other major transport, health and school infrastructure, free kinder, and mental health hubs.

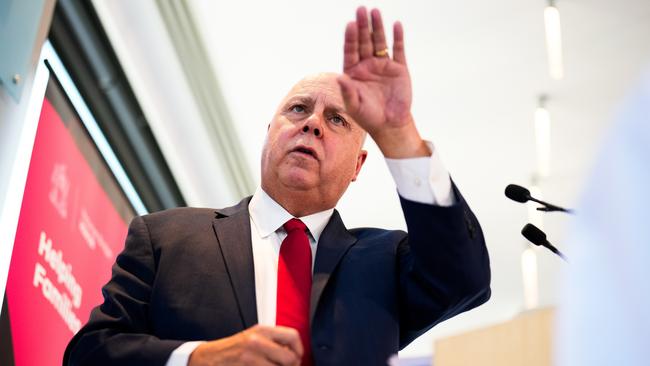

Releasing his 10th budget, and Jacinta Allan’s first as Premier, Treasurer Tim Pallas on Tuesday declared it to be a budget of “sensible choices”, focused on “helping families” and “building a stronger future for Victoria”.

But the state is now on track for a yearly interest bill of $9.4bn – or $25.8m a day – by the end of the forward estimates, up from a current annual bill of $6.5bn.

The interest will service net debt, which is projected to reach $156.2bn by June next year (up from $151.2bn estimated in last year’s budget), rising to $187.8bn by June 2028 – or $25,354 for every Victorian.

The soaring debt comes despite a ballooning tax take – with state taxation revenue forecast to reach $39bn this year, and grow by an average 5 per cent per year over the forward estimates.

The growth in the public service wage bill is similarly set to continue apace, from $36.5bn currently (up from $35.9 estimated in last year’s budget) to $39.9bn in 2027-28 – more than double the $18.7bn bill Labor inherited when it came to government in 2014.

Mr Pallas spruiked a higher than previously predicted operating surplus of $1.5bn in 2025-26 (up from a $1bn deficit predicted in last year’s budget), and $1.6bn in 2026-27 (up from a 1.1bn surplus), and $1.9bn in 2027-28.

He sought to frame the debt in the context of a growing state economy, with debt as a proportion of gross state product set to reach 24.4 per cent in June 2025, rising to 25.2 per cent in 2026-27, and decline by a wafer-thin 0.1 per cent 25.1 per cent in 2027-28.

The ratio compares with net debt previously peaking at 16 per cent of GSP in 1993, during the post-Cain-Kirner recession.

The budget is predicated on the state economy continuing to grow at a phenomenal rate, with the Treasurer forecasting gross state product will increase from about $600bn today to almost three-quarters of a trillion dollars by the end of the forward estimates – a 25 per cent increase in four years.

Mr Pallas said the increasing debt would enable the government to fund “productive infrastructure that will grow our economy and deliver benefits well into the future”, but indicated infrastructure spending would decline – from $24bn in 2023-24 to $15.6bn by the end of the forward estimates.

Key to the reduced infrastructure spend is the abandonment of Melbourne Airport Rail, with the government blaming Melbourne Airport, which wants an underground train station, for an impasse that sees the project “now at least four years delayed.”

Despite Victoria’s Auditor-General last year forecasting an expected cost blowout of up to 20 per cent – or $6.9bn – for the first stage of the controversial Suburban Rail Loop, Tuesday’s budget papers continue to cost it at the original estimate of $30bn-$34.5bn, only $11.8bn of which has so far been funded by the state government.

The government maintains the other two-thirds of the project will be funded through “value-capture sources” and its own funding being matched by the federal government, even with no commitment from Canberra to build on the $2.2bn of federal funding already announced.

The Treasurer took aim at what he argued was the federal government’s long-term failure to adequately fund Victorian infrastructure, saying the state had received $8.3bn less than its population share in funding between 2014-15 and 2022-23, netting $9bn rather than $17.3bn.

“Over the same period, NSW has received $2.7bn more than its population share of infrastructure funding; $24.4bn instead of $21.5bn,” Mr Pallas said.

“All we are asking for essentially is our fair share, we’re not asking to get over the odds. Since the GST was introduced, Victoria has never received its population share of the GST, meaning Victoria has subsidised federation to the tune of $30bn.”

Mr Pallas said the government would glean savings from “winding up Covid-era programs that are no longer needed” – cuts that are likely to prove controversial where they impact services in sectors including health, mental health, education, disability, seniors and community crime prevention, many of which are experiencing demand that has been sustained post-pandemic.

He also pledged reductions in the government’s advertising spend and savings from a cut in public service office space, and blamed sustained low unemployment for delays to the rollout of free kindergarten and local mental health and wellbeing hubs.

A five-year extension, to 15 years, on what was intended to be the rollout over a decade of the “mental health and wellbeing locals”, comes despite forecast revenue of more than $1bn in 2024-25 from the payroll tax levy introduced two years ago to fund the state’s response to the mental health royal commission.

The government also announced it would extend the investment profile of its beleaguered start-up fund, Breakthrough Victoria, from 10 to 15 years, to allow “more time to review and be selective about quality investments”.

Victoria’s increased tax take is primarily expected to be driven by payroll tax, land tax and land transfer duty, with revenue from land tax alone – a key plank of the Covid levy introduced in last year’s budget – forecast to be $6.5bn in 2024-25, then grow by an average of 6.2 per cent per year over the forward estimates.

New spending commitments include $287m to fund $400 vouchers for schoolchildren, as well as $964m for the state’s pothole-riddled roads – up from $770m in road funding in 2023-24 and only $593m in 2022-23, compared with $823m in 2020-21.

There is also $233m to train drivers, manage timetabling and conduct final testing of the Melbourne Metro Rail Tunnel before it opens next year, which comes on top of $2.74bn in blowouts already added to the cost of what is now an almost $13bn project.

Despite federal Environment Minister Tanya Plibersek vetoing state plans for an offshore wind terminal at the Port of Hastings in December, Tuesday’s budget includes “$17m to continue planning and designing a renewable energy terminal at the Port of Hastings”, as well as $18m “to plan for offshore wind generation”.

The budget estimates wage growth will remain steady at 3.75 per cent in 2024-25 – the same as 2023-34 – with the population set to grow by 1.8 per cent in 2024-25 – down from 2.3 per cent in 2023-24 – on the way to a state population of 10 million by 2050, up from seven million now.

S&P global ratings analyst Anthony Walker warned pressure on Victoria’s AA credit rating – already the lowest of any Australian state – “could build if financial management wanes”.

Opposition Leader John Pesutto said the budget was the “culmination of a decade of financial mismanagement under Labor”.

The Victorian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and Australian Industry Group welcomed the fact the budget contained no new business taxes, in contrast with recent previous budgets, while the Property Council said it was “deeply concerned by the complete absence of any positive action to alleviate the immense fiscal burden on the industry”.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout