Tim Pallas: Creatureof union reform blows the bank

For Tim Pallas, Tuesday’s Victorian budget is more about the fight for his political credibility than the medium-term future of the government.

No one other than the four premiers has been more baked into Labor decision-making than 64-year-old Pallas, who was chief of staff to then Labor leader Steve Bracks in 1999, helping to engineer the seemingly unwinnable election that triggered the state ALP dynasty that has ruled Victoria for nearly 21 of the past 25 years.

A creature of the Victorian Right during his earlier years, Pallas was schooled in his sub-faction’s commitment to function in a manner that made Labor and the unions able to deal with business.

Pallas had risen through the Federated Storemen and Packers Union, which drove national industrial reform, the union thriving under the work of powerbroker Bill Landeryou and former federal leader Simon Crean.

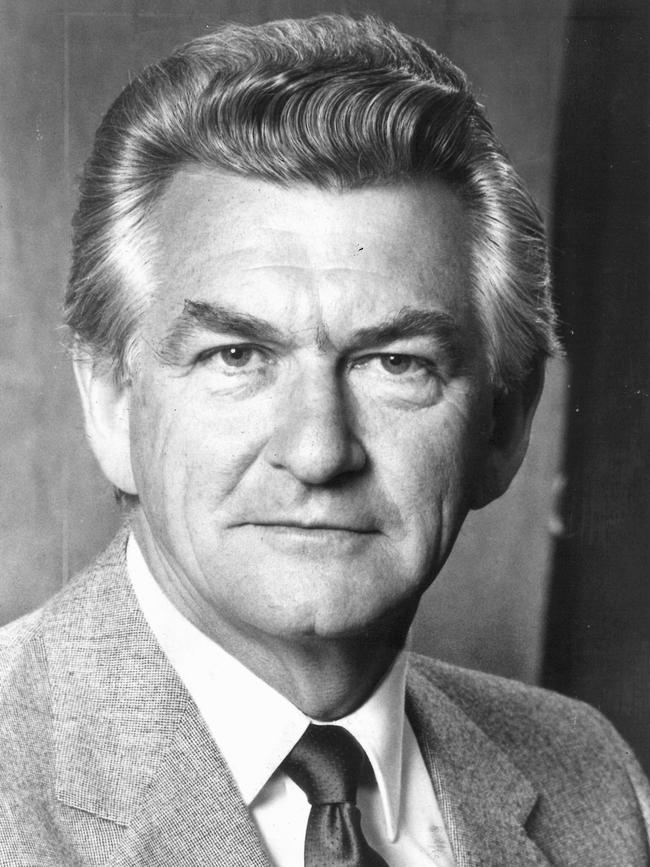

More specifically, he was in the orbit of former prime minister Bob Hawke and former ACTU boss Bill Kelty, the latter having authored the Prices and Incomes Accord.

The son of a doctor, Pallas had a front-row seat at the reinvention of Labor nationally under Hawke and former treasurer Paul Keating and then Victorian Labor.

In his inaugural speech in 2006, he said Kelty “showed me the value of co-operative interaction with government”.

“Thank you to Bob Hawke, a great advocate for working people, a great prime minister and a great friend and counsel to me,” he said.

But his strongest praise was for Bracks, who led Victoria from 1999 to 2007 in a manner that was relentlessly understated but fuelled by a deep, instinctive understanding of the three crucial voting groups in Victoria – the regions, the outer suburbs and the politically difficult inner suburbs, where he lived as leader.

Principally, Bracks, briefly treasurer as well, was driven by fiscal responsibility.

“What the premier has impressed upon me in word and deed is this: government is a privilege, not a right,” Pallas said in his speech. “That integrity and work ethic was apparent from day one in the opposition rooms and has been evident each and every day since.”

No one has ever questioned Pallas’s work ethic but plenty are lining up to savage his failure to push back against the politically motivated spending in the past near decade of Labor rule that has put Victoria in a budgetary vice.

While the last great Labor mess more than 30 years ago coincided with an economy-wide collapse in Victoria, the employment numbers in 2024 are far stronger, perhaps explaining in part why the government has remained popular. Victoria is having a lumpy rebound, just like much of the rest of the democratic world.

In 2024, way too much debt (like 1992), stubborn inflation and grinding demand for more services to fulfil a climbing population still bruised by the government’s response to the pandemic have combined to deliver a post-Covid cyclone of political uncertainty.

The departure of Daniel Andrews last September created what looked like the perfect opportunity for new Premier Jacinta Allan and Pallas – both products of the Bracks-John Brumby years between 1999 and 2010 – to reset the budget and turn their backs on fiscal profligacy.

That hasn’t happened so far, with Allan still backing the $125bn Suburban Rail Loop project despite it looming as one of the nation’s most expensive infrastructure experiments and pushing ahead with billions of dollars of other spending commitments that could have been delayed or shelved the moment Andrews left. This includes the $2.6bn earmarked for the regional areas that missed out on the Commonwealth Games.

To retain any credibility, Pallas – who recently transitioned to the Labor Left – has been under pressure from the business community to stop taxing so heavily and find other ways to right the ship.

He has agreed to spare developers in outer suburban areas and will instead focus on stripping out even more Covid-era spending that has been lingering in government portfolios. “We have never tried to sugar-coat the budget,” he said on Thursday.

In a recent interview, Allan bristled when asked what it was like to be in charge of a government that was running out of money.

“In terms of your reference to the budget, it’s not correct because you can see every single day we are continuing to deliver services,” she told the ABC’s Raf Epstein.

Allan also has made the point that governments can’t run budgets in 2024 the way they were run 20 years ago.

This is a reasonable position, with big infrastructure programs under way along the eastern seaboard, but NSW has not racked up the sort of debt that has so exposed Victoria.

One long-term Labor observer describes the Allan government as being like Romania after the overthrow of Nicolae Ceausescu in 1989. “They know they are in trouble but it’s such a happy post-Dan vibe,” he says.

With modern Labor, it’s prudent to pretty much ignore a lot of what is said publicly, certainly in front of the media.

For decades, ministers have been taught to parrot lines that will be replayed on the television news rather than have an honest discourse with the community.

Privately, the old Labor guard is furious – bewildered – with the way the state’s finances have been run into the ground.

“It’s a product of weakness by Tim – he didn’t have the courage to take Daniel on,” a senior Labor figure says. “It’s been a joke for years that he would give everything Daniel wanted, plus one of his kids, if it meant keeping him happy. No one wanted to push back but sometimes you have to.”

So how bad are the numbers?

In March, it was revealed that Victorian debt had blown out by a further $11.7bn to more than $126bn and credit ratings agency S&P warned that the state was hurtling to almost double that number, which would be a quarter of a trillion dollars.

The rise was blamed by Treasury on an increase in borrowings to fund the state’s groaning capital works program.

Net debt is forecast to hit $135bn this year compared with NSW’s $95bn. Even if you strip out the $31bn worth of Victorian Covid spending (ignoring all NSW’s measures), Victoria has a relative debt issue, fuelled by past spending initiatives and a challenging infrastructure spend and pipeline. Debt will inevitably keep rising.

The question is by how much.

A key part of the debt farce is major project spending and mismanagement.

Allan announced in December last year a $10bn blowout in one road project in Melbourne’s northeast, has pushed ahead with a multibillion-dollar level crossing removals process that could easily be stalled and continues to back the $125bn (nobody knows the precise number) Suburban Rail Loop.

The SRL runs the risk of ending up like former South Australian premier Don Dunstan’s proposed second city of Monarto, which is now a zoo.

The SRL is a cross-city rail loop that supposedly would transform travel for decades but cost eye-watering sums of money at the same time that the future of how we move around large cities is – potentially quite literally – up in the air.

No one knows the full cost of the multistage adventure.

The first stage of the SRL is predicted to cost up to $35bn and runs through key middle-suburb seats that Labor wants to win and hold. Like all things, it’s not all bad, it’s just not affordable. Pallas and Allan could almost immediately deal with some of the state’s long-term debt issues by dumping or delaying the SRL and scaling back on other key capital promises.

One theory is that Allan is persisting with the SRL because the project is too far advanced to kill key contracts.

To fund a lot of the challenges, Pallas has resorted to a string of taxes, key of which have been focused on property, the Victorian golden goose. Taxation revenue is forecast to be $36bn by mid this year and grow by an average of 5.1 per cent across the forward estimates.

The budget update says revenue from taxes on employers’ payroll and labour, inclusive of payroll tax, a Covid debt levy and a mental health and wellbeing levy is forecast to be $10.3bn in 2023-24.

It can feel like a national sport to bag Victoria after the pandemic response, but there is some limited blue sky in the so-called Big Build. Unlike the John Cain-Joan Kirner recession, a lot of the spending has been on productive infrastructure.

Deutsche Bank recently poured a bit of cold water on the debate, suggesting Victoria’s exposure was less extreme than the past, although it acknowledged that net debt was at 1992 levels but half that under Henry Bolte in the early 1960s.

The history is, though, that Victoria’s finances were largely restored in the ’90s via asset sales and there are deeply limited 2024 sell-off options for Pallas, or whomever might succeed him.

The politics of Tuesday’s budget are weird. On so many levels, Labor should be cooked. But Labor’s polling has shown, for years, that voters love the Big Spend. They love having new hospitals, they love railway crossing removals, they can even love cancelling a Commonwealth Games when the government shovels the same amount of money ($2.6bn) back into the place where the events were going to be held.

This has been the key to Labor since it was elected in late 2014. Keep shovelling money out into the suburbs and the punters will love it.

At the same time, the perception is that the Victorian Liberal Party is obsessed with debates about men in women’s clothing and an internal court battle. Why vote for a party that devotes so much time to fighting itself after nearly 10 years in opposition?

The old guard of the Victorian Right knows Labor’s fiscal strategy was only sustainable if major projects were managed well and were achievable. This hasn’t been the case in Victoria.

Since last September, Allan has moved her Left-dominated government closer to the political centre, with an eye on the next challenge: how to placate disenfranchised voters in the outer suburbs who have largely missed out on the infrastructure but worn all the growing pains.

For Pallas, Tuesday’s budget is more about the fight for his political credibility than the medium-term future of the government.

If the Victorian finances are not fixed, with some urgency, he will go down as the 2024 equivalent of Rob Jolly, the Labor treasurer during the Cain years.

Events, including the Pyramid Building Society collapse, swallowed Jolly. Pallas is in the same, treacherous territory.

It’s not what his mentors would have wanted.

When Victorian Treasurer Tim Pallas delivers his 10th budget on Tuesday he will entrench his place at the top table of the state Labor establishment for the past 25 years.