The day Malcolm Fraser was captured by student protesters

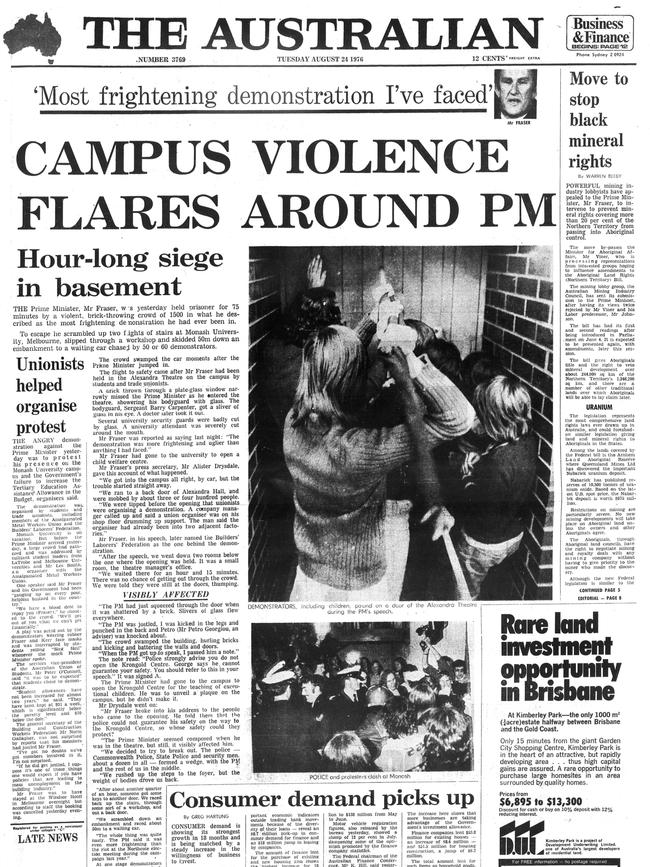

Student protesters managed to hold Malcolm Fraser hostage in a campus basement for 75 minutes before he was finally rescued. It was as shocking as it was scandalous at the time | WATCH

The campus was a hotbed of far-left political activism. Fraser, characteristically aloof, arrogant and undeterred, accepted the invitation. Radical students saw an opportunity and initiated a massive and at times violent protest. Fraser was forced to leave the Alexandra Hall mid-speech and ended up in the basement. The prime minister effectively had been captured and was trapped for more than an hour.

The protesters had not planned to imprison Fraser and hold him hostage, but events spiralled out of control and security forces proved so inadequate that this was the result. Some thought Fraser escaped through a window, but a scrum of police eventually rescued him from the building. It was as shocking as it was scandalous at the time.

This extraordinary event is the subject of a fascinating new documentary, How to Capture a Prime Minister, directed and produced by Gary Newman. It has been more than 10 years in the making and finally will have its premiere on Saturday, marking a momentous day in Australian political history. On that day, Fraser was sworn in as prime minister when governor-general Sir John Kerr used his vice-regal powers to dismiss Gough Whitlam’s government after it had failed to secure passage of its budget through the Senate. The delaying of supply by the Liberal-Country Party opposition was the event that propelled Fraser to power. He won a landslide election victory in December 1975.

The dismissal of the Whitlam government left deep scars in the Australian polity. There were protests around Australia in response to the unprecedented intervention by Kerr on November 11.

Paul Keating, a cabinet minister at the time, told me the dismissal injected a poison into the political bloodstream of the country and it has never recovered.

Fraser and Kerr, along with chief justice Sir Garfield Barwick, who advised Kerr on the use of his reserve powers, were forever cast as principal villains of the dismissal. Kerr could rarely go anywhere without meeting a hostile demonstration and exited the vice-regal office in December 1977. He spent his retirement years in England. But Fraser continued on, winning re-election in December 1977 and again in October 1980.

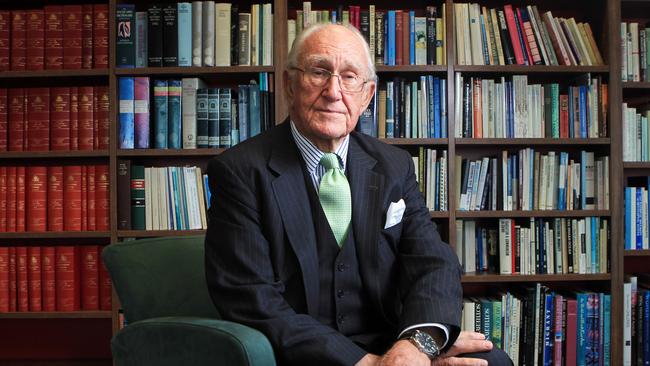

The documentary includes interviews with the ageing student protesters, university administrators and security personnel, Fraser’s former staff and Fraser himself. Newman interviewed Fraser in 2013. The documentary uses compelling animations of maps to show how the protest developed and the prime minister was trapped, alongside archival documents, news footage and still photographs.

Before Fraser arrived on campus on August 23, 1976, ASIO had warned of the planned protest by students rallying under the banner of “No Welcome for Malcolm”. University officials had advised students not to protest against the prime minister’s visit. They were also undeterred.

The students were motivated by the dismissal, accusing Fraser of being guilty of “a vicious assault” on democracy. They also were motivated to protest against his government’s policies and its cost-cutting agenda, saying Fraser represented “the greatest threat to education” in Australia at that time.

When Fraser arrived, he was met by a throng of about 1500 protesters, some from other universities in Melbourne. They were burning effigies, waving placards and flags, and some were raising their hands in a fascist salute. Alister Drysdale, Fraser’s press secretary, recalled the scene as “frightening”. As they pounded on the doors, smashed windows and breached the building, Drysdale passed a note to Fraser saying they had to evacuate.

The problem was, where to go? Fraser was trapped. He was led down a series of corridors and found himself stuck in a small lower floor room. The response from campus security and local police was inadequate. About 75 minutes passed before the police gained entry and escorted Fraser through the crowd and out of the building, where he slid down an embankment to a waiting car, and to safety.

Several of the students involved in the protest, including Brian Boyd, Bill Mountford, Dick Gross, Bruce Hearn, Jeannie Rea and Red Bingham, are interviewed for the film. They describe Fraser as like Darth Vader, an evil establishment figure who was rolling back the Whitlam government’s agenda. There were cuts to social welfare programs, education and the dismantling of Medibank. It was a time of intense activism that had been boiling through the 1960s and into the ’70s with the Vietnam War, the women’s movement and gay rights looming large. There were rallies and strikes to oppose the Springboks rugby union tour, defend Medibank and support Indigenous land rights. There were suspicions of CIA espionage in Australia and concerns over ASIO surveillance that percolated through student groups.

Yet Lindsay Tanner, a long-haired student at the time and later a Labor cabinet minister, recognised Fraser was somewhat maligned. Other former students find it difficult to reconcile their hatred of Fraser with his progressive legacy on refugees, apartheid, land rights. The irony is that Fraser maintained free university education. And the protest stopped the opening of the Krongold Centre, causing distress for parents.

What did Fraser make of all of this? Long into the film, Fraser gives us his perspective. It is a compelling interview. “I thought this crowd was unlike any other,” Fraser says. “In the 1970s, people didn’t look at what I was doing. They really didn’t.” He was always committed to individual liberty, freedom and human rights.

The students insist they never planned to capture Fraser. The protest simply got out of control. But, almost 50 years later, they have few regrets.

How to Capture a Prime Minister will premiere at the Capitol Theatre in Melbourne on Saturday and screen in Canberra on November 22 (Dendy Cinemas) and in Sydney on November 25 (Chauvel Cinema).

In the winter of 1976, Malcolm Fraser was invited to open the Krongold Centre, a new education facility for special needs children, at Monash University in Melbourne. The prime minister, in office for just nine months, had been a lightning rod for protests given his role in pushing the political system to the brink in the constitutional crisis of October-November 1975.