Fraser reappraisal is timely for a lost and broken party

He is not revered like Howard or Menzies, but the ex-PM can offer the Liberals valuable insights.

The Liberal Party has found it difficult to reconcile the legacy of its third longest serving and third most electorally successful leader, Malcolm Fraser. He is seldom mentioned by modern Liberals, is hardly ever referenced by contemporary leaders and is at risk of being lost to history.

Fraser was a persistent critic of the Liberal Party, indicting it for becoming unmoored from its liberal roots, and was often at odds with John Howard over the direction of his government. He eventually resigned from the Liberals in 2010. Nobody in the upper echelons of the party mourned his departure.

Some Liberals could never pardon him for undermining John Gorton and sparking the events which led to his downfall with a lethal parliamentary speech in 1971. He could never be embraced by Labor because of his ruthlessness in blocking the Whitlam government’s budget and becoming prime minister as a result of vice-regal intervention.

Fraser lived a long life (1930-2015) and cut a lonely figure in the ex-prime minister’s club. Yet Fraser, despite being forgotten by Liberals and never forgiven by Labor, remains the fourth longest-serving prime minister overall, won three elections and has a substantial record of achievement although his government (1975-83) was also one of missed opportunities.

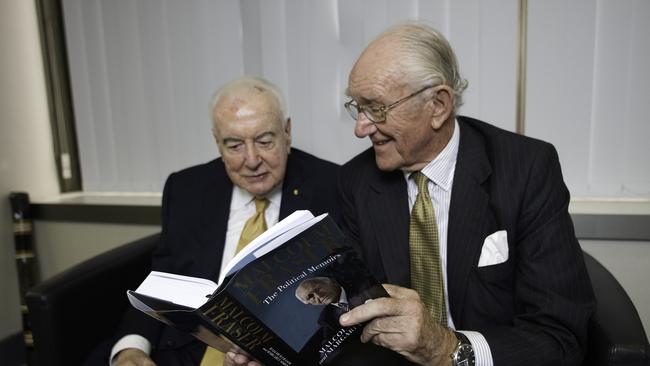

Denis White joined Fraser’s staff in 1980 and served as director (chief of staff) from 1982 to 1983. He has written a monograph, Fraser in Office, which provides a favourable reassessment of the 22nd prime minister. David Kemp, who also worked for Fraser, has written a foreword. Nick Cater contributes an introduction.

The monograph provides insights into Fraser as a person, politician and prime minister. It was Fraser’s belief in the individual to determine their own future that inspired a career in politics. He saw politics as “the great profession” because of its determining power to shape the future.

“(Fraser) believed in free will, and the acceptance of responsibility that goes with it,” White explains. “He did not believe that human history is inevitable – on the contrary, he had a strong sense of personal responsibility for creating outcomes.”

When Fraser quipped that “life wasn’t meant to be easy” in 1971, what he meant was that we face challenges and obstacles in life and how we deal with them, successfully or otherwise, determines the course of human history.

White sketches the Fraser approach to politics and government. He was driven, determined, analytical, methodical, unflappable and formidable when challenged. He worked long hours and was demanding of ministers, public servants and staff. He was outcomes-focused and solutions-driven. He had authority and stature but in private could be reserved, even shy.

Kemp writes that few knew Fraser better than White. They worked closely in government and collaborated during Fraser’s post-prime ministerial years. White was a political philosopher and academic. Fraser sought to improve the rights, liberties and dignity of the individual and, with White and Kemp’s help, applied this to policymaking.

It is striking to consider how clearly many of Fraser’s signature achievements have a liberal ethos that runs through them.

His government empowered the individual with a new Human Rights Commission, the Commonwealth Ombudsman, freedom of information laws, the Administrative Appeals Tribunal, the creation of SBS, the promotion of multiculturalism, the welcoming of refugees, land rights legislation, and opposing racial apartheid in South Africa.

Fraser came to power when Gough Whitlam’s government was dismissed by the governor-general in 1975. This had an impact on how Fraser governed. Australians were split. Fraser was seen by some voters as aloof and arrogant. His ministers, Howard and Andrew Peacock, told me that Fraser was cautious and careful, given the divisions that had been unleashed.

The government was not able to deal effectively with skyrocketing inflation and unemployment. It was a time of industrial unrest, with Bob Hawke as ACTU president, and confrontation between employers and employees. The dollar was overvalued and industry was still adjusting to the 25 per cent across-the-board tariff cut of the Whitlam government.

Fraser supported smaller government, fiscal restraint and prudent management of the nation’s finances but these ideals were easier said than put into action. The size of government expanded despite claims about Labor’s budget recklessness. The Fraser government spent and taxed more than the Whitlam government, as a percentage of GDP. The landmark deregulatory economic reforms, which never had Fraser’s support, would be left to the Hawke government.

White makes astute observations about Fraser’s policies in support of land rights and multiculturalism which affirmed the dignity of the individual; his three successful referendums to change the Constitution which were practical and democratic; and his expansion of environmental protection measures for the Great Barrier Reef and Kakadu National Park, and a ban on whaling. It was a Liberal government from a bygone age.

Recent Liberal leaders have failed to develop what Robert Menzies called a statement of “political faith”. In other words, a clear sense of identity, values, vision and purpose. Fraser’s speeches, however, presented a coherent philosophy to articulate the policies and programs of his government. Liberal leaders do not speak like Fraser did, and extracts from his speeches in the monograph are useful reminders.

In 1973, Kemp wrote an important essay, titled “A leader and a philosophy”, which argued that leaders are more effective in rallying supporters and persuading voters if they have a clear set of beliefs that can give their party incentive and direction.

Kemp urged leaders to become an “expounder of a philosophy or ideology”. The White monograph shows how Fraser sought to govern within a liberal philosophical framework.

The Liberal Party is now facing an existential crisis that goes to what it believes in, what it wants to achieve, and who it represents.

The loss of 18 seats, including in its blue-ribbon heartland in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth, should prompt soul-searching. This reassessment of Fraser, his approach to politics and government, and his legacy, could not be timelier.

Denis White’s Fraser in Office is published by Jeparit Press, an imprint of Connor Court.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout