The fact that subsequent IGRs have been produced at odd intervals underscores the point that the IGR is now an intensely political document designed to fit policy priorities and approaches of the government of the day.

It was Labor treasurer Wayne Swan, for instance, who brought forward an IGR and included a chapter on climate change for the first time.

There is no doubt the first IGR was the best. It introduced us to the three P’s: population, participation and productivity. We were warned about the potential consequences of an ageing population and the fiscal consequences. This single message has essentially remained the same in all the IGRs.

But here’s the thing: the 2002 IGR predicted Australia’s population would be 25 million in the early 2040s. We made 25 million in 2018, largely because of a surge in migration from the beginning of that decade.

The assumption was also made that productivity would grow by 1.75 per cent a year. That turned out to be far too optimistic and the IGR released yesterday works on the basis of 1.2 per cent a year.

This much lower figure may still be too hopeful given recent woeful productivity performances.

Two standout factors have worked significantly in Australia’s favour over the past two decades. First, there has been the substantial lift in the workforce participation rate, due mainly to rising female participation but also older workers continuing to work.

In 2002, the overall participation rate was 63.1 per cent; it is now 66.7 per cent. That might not look like a big difference but it has a huge impact on GDP growth.

The other factor has been the dramatic rise in the terms of trade (the ratio of export to import prices) that occurred from the middle of the first decade, pausing with the onset of the global financial crisis, and rising again to record high levels.

Aligned to the booming Chinese economy, the lift in commodity prices has added as much as 10 per cent to our living standards. It is one reason a degree of pessimism about our future seems justified as our reliance on China as our major trading partner has a distinct downside when growth in that country begins to falter.

Other factors such as rising protectionism and geopolitical instability add to a sense of gloom.

Thursday’s IGR contains some unconvincing analysis on the economic consequences of climate change and the impact of decarbonisation. In terms of the former, the best overseas studies point to an impact of about 1 per cent of GDP in the latter half of the century. Even if it were double that in Australia, it would still be highly manageable given the scope for adaptation.

There is also little doubt that enforced decarbonisation is, and will be, a massive and expensive drag on productivity: you only have to think of the low energy density of wind and solar, the need for redundancy in the system and the lost time associated with electric vehicles.

Just because something requires billions of dollars of investment doesn’t mean it boosts living standards – just think of the old Soviet Union and its extremely high rates of investment.

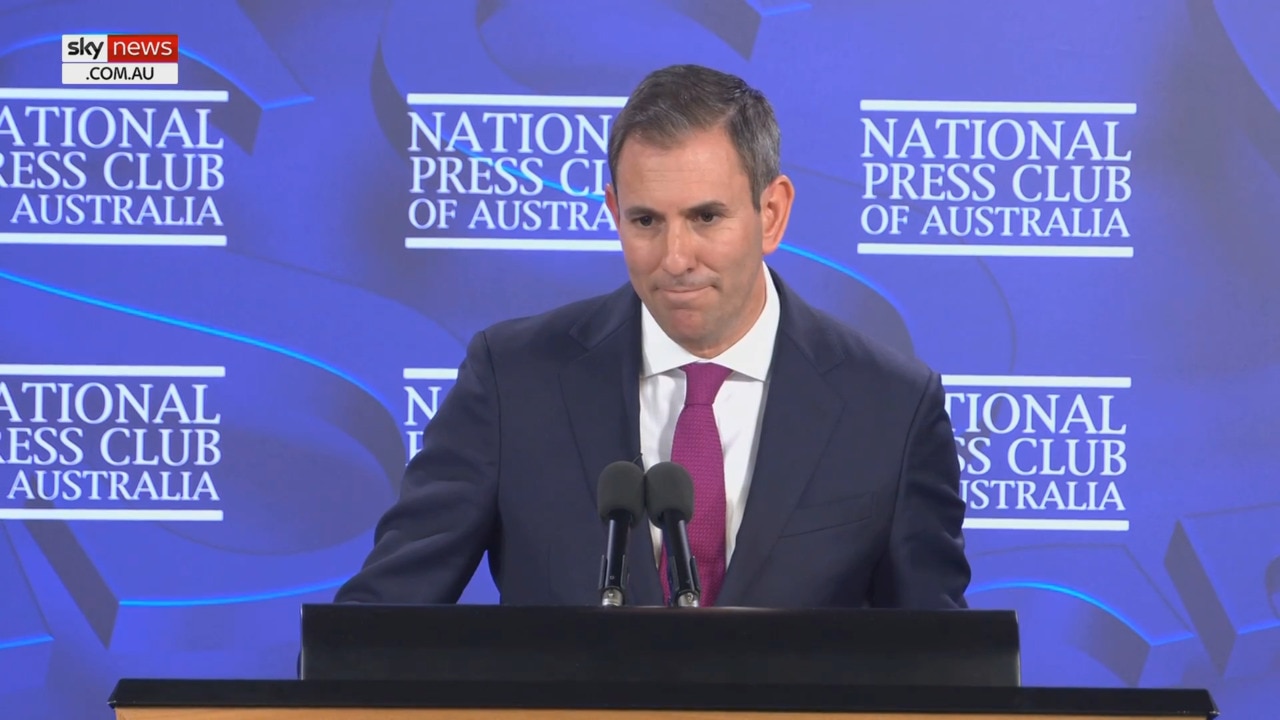

There is no doubt the current Treasurer, Jim Chalmers, is a good communicator. The real problem is that the messages are incoherent and unpersuasive.

Does he honestly think that re-regulating industrial relations is the way forward? Does spending more on education and training make any sense, given the obvious lack of productivity dividend?

Surely he can’t be serious that we can run decades of budget deficits – something will give, and it will hopefully involve a frank assessment of what governments should and shouldn’t do.

The first Intergenerational Report was released in 2002 when Peter Costello was treasurer. It was the result of the Charter of Budget Honesty 1998, which includes the requirement that an IGR be produced every five years, focusing on the net financial worth of the federal government.