Anthony Albanese’s quiet advantage: Underestimate this Labor underdog at your peril

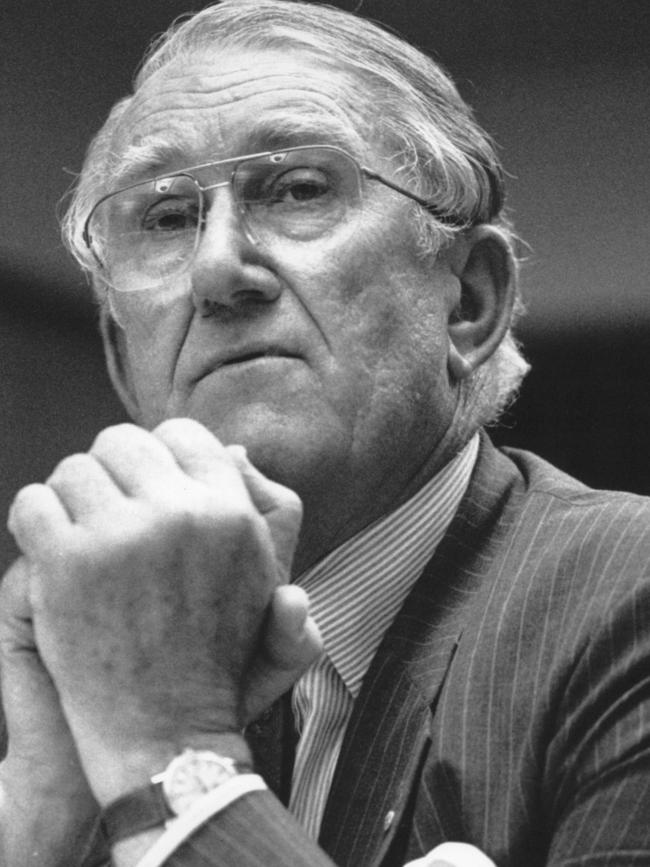

There is a trap for the Labor critics and his political opponents who have judged Anthony Albanese to be a oncer and an easy beat ‘worse than Whitlam’. It’s the same trap Labor members fell for in the 1990s and 2000s when they convinced themselves that John Howard was unelectable.

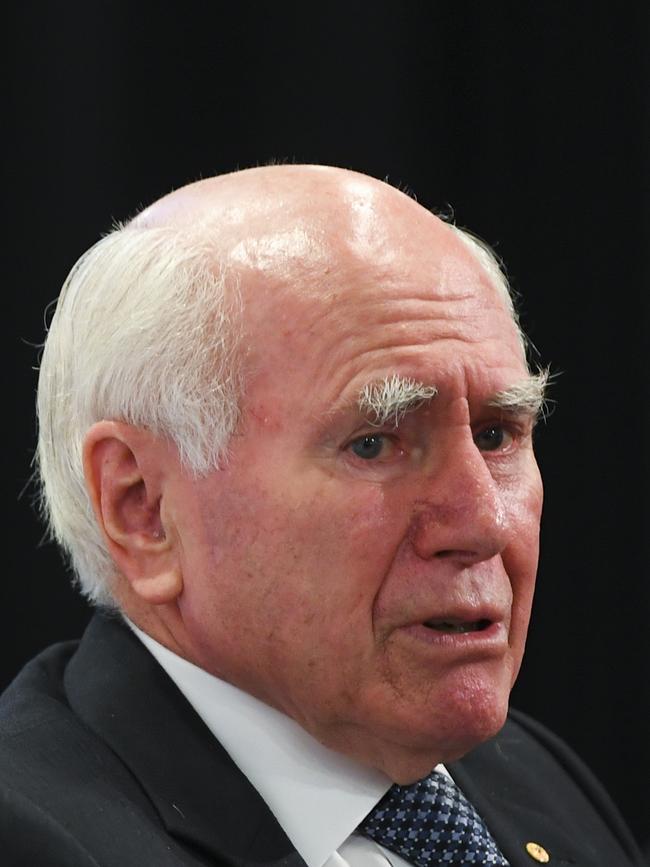

Why is Anthony Albanese always so underestimated?

His critics say it’s because he’s underwhelming and underestimation is what he is due.

There are Labor colleagues who say he became Labor leader by default after the other candidates failed or fell out and he became Prime Minister by accident.

But there is a trap here for the Labor critics and his political opponents who have judged Albanese to be a oncer and an easy beat “worse than Whitlam”.

It’s the same trap Labor members fell for in the 1990s and 2000s when they convinced themselves that John Howard was unelectable and kept repeating it to themselves after every Howard victory.

It’s true Albanese did not have a sense of destiny shared by some other leaders who believed they would become prime minister and deserved to be so, such as Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke, Paul Keating, Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull. It’s also true his leadership of the ALP and becoming Prime Minister came only after a long gestation, little expectation and some serious disappointment.

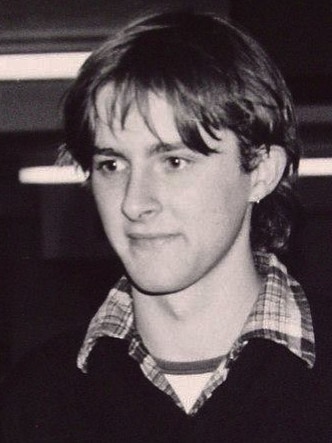

Indeed, 29 years ago, in his May 6, 1996 maiden speech to parliament – as the youngest MP after the Howard election victory – Albanese spoke of his highest expectation as a new MP under Kim Beazley’s leadership as representing the people of his inner-west Sydney seat of Grayndler.

Yet the 33-year-old delivered a singular political declaration in that speech – after the customary tributes to his mother and staff – when he tore into the media for underestimating him.

Even at that tender age it was The Australian that bothered him most: a column by psephologist Malcolm Mackerras, which on October 5, 1995, had predicted Albanese would not win at his first attempt to enter parliament and would lose to the No Aircraft Noise party.

Likewise, The Sydney Morning Herald columnist Paddy McGuinness said Albanese, a “scion of the Labor Left”, would be beaten by the anti-aircraft noise party.

Albanese declared in parliament: “I am pleased to have disappointed them.”

He concluded: “For myself, I will be satisfied if I can be remembered as someone who will stand up for the interests of my electorate, for working-class people, for the labour movement and for our progressive advancement as a nation into the next century.”

Since then, of course, Albanese has continued to win in Grayndler against strong Greens challenges. He has gone on to become deputy prime minister under Kevin Rudd for three months in 2013 after they dumped Julia Gillard, to be defeated in a leadership ballot by Bill Shorten and to tough out Tanya Plibersek’s bid to become Labor leader.

He did defeat Scott Morrison to become Prime Minster and now leads Peter Dutton in the polls a week out from his first election day as PM.

Yet there is still the refrain that he is underestimated. Why?

Well, the obvious answer is he is underestimated because he doesn’t look the part of a prime minister; he looks more like a tourist having his photograph taken at the Great Wall of China where Whitlam stood 50 years previously than a PM himself and is more comfortable at a local government meeting than a G20 summit.

His portfolios of local government and infrastructure gave him a detailed knowledge of the geography and politics of Australia on the ground. Former Nationals MP and now long-term north Queensland independent Bob Katter gets on well with Albanese.

But there are other reasons: Albanese is a factional ninja out of the shadows of the opaque and abstruse world of the Labor Party and the labour movement; his exercise of power in this world is kept hidden. He revels in being underestimated – it is a perverse advantage that makes rubbing his critics’ noses in his success all the more satisfying.

Albanese has succeeded. Given he has become Prime Minister that is self-evident. The challenge for him is to appear like a forthright leader exercising his authority while maintaining his underestimated underdog status.

The Prime Minister’s political style has been shaped by decades of internecine feuds, often at a local council level, that have made him a relentless campaigner against his foes and given him a raw understanding of grassroots politics that doesn’t necessarily fit the more elevated view of a national leader on a world stage. It may not be pretty but it is effective.

This week, in the latest televised leaders’ debate, Albanese had to combat the dangerous claim that he was weak. He did this with a declaration of tough but hidden power.

After having played down divisions at the time within Labor over the AUKUS nuclear-powered submarine deal, Albanese had to lift the veil and claim victory behind closed doors over his own Left faction.

He said: “On issues like nuclear-powered submarines, not everyone in the Labor Party was wrapped by that at the beginning.

“I took the argument to the ALP national conference, put it through. We’re putting it in place. I’ve been in public life … for a long period of time and you don’t get to be prime minister and to lead the Labor Party without a toughness. It’s a tough forum,” he said.

It must be remembered that Albanese’s Left faction has the numbers to control the agenda at the national conference yet, in conjunction with union leaders, he passed that motion, which many in the Left opposed. Because he prefers to be underestimated and quietly overperform behind the scenes, Albanese played down his brutal overruling of his potential leadership rival, Environment Minister Plibersek, on unpopular resources laws in his must-hold state of Western Australia and on salmon farms in his hoped-to-gain state of Tasmania.

Albanese also is renowned for hand-picking candidates – directly overruling state branches – with a penchant for selecting people with local council experience such as Bega Valley Shire mayor Kristy McBain in Eden-Monaro in the 2020 by-election and Georges River councillor Ash Ambihaipahar in Barton to replace Linda Burney for this election as well as former Greens candidate Carol Berry in the NSW south coast seat of Whitlam.

He bristles at suggestions he backed the selection of former NSW premier and senator Kristina Keneally in her failed bid for the western Sydney suburbs seat of Fowler – which was won by independent Dai Le – and glows at suggestions he backed the 2025 Labor candidate Tu Le.

The battle of the Les will be a crucial outcome for Albanese’s aim of majority Labor government as he targets independents and Greens while claiming to have enough support already from the crossbench to govern in minority.

Albanese is directly hands-on and micromanaging these selections but the exercise of his authority remains masked.

This is not – as Albanese said himself in the debate – an exercise of soft power but a tough, brutal and vindictive use of power to stifle opponents, pay back those who have crossed him or who are “unwilling” to accept his way.

The problem for Albanese is that he has contradictory aims: he wants to exercise his authority; to win, he wants to be seen to be a tough leader; and he still wants to appear to be underestimated to identify with different groups that feel disenfranchised.

As part of his effort not to be seen as a cruel political leader, Albanese points to the lack of sackings in his first term as evidence of stability but also of his seeming collegiate style.

“I think that we need stability,” he told Inquirer this week in an exclusive interview.

“My government is the most stable first-term government that there has been in at least 50 years, you know. More stable than the first terms of Whitlam, Fraser, Hawke, Howard, Rudd, Abbott, etc, no scandals, no ministerial resignations. Order, we’ve done what we said we would do. We’ve dealt with incoming pressures that weren’t envisaged.”

Of course, there were bungles that should have led to ministerial sackings but Albanese’s mania for stability would not allow it and he used his skills as a retail politician prepared to deflect and distract – and to do so successfully – and take advantage of changed circumstances.

And all the time he was claiming to be underestimated and unfairly criticised.

Such an approach has worked for him during three years as opposition leader and may well again after three years as Prime Minister, but if it doesn’t it will be because he was over-estimated.