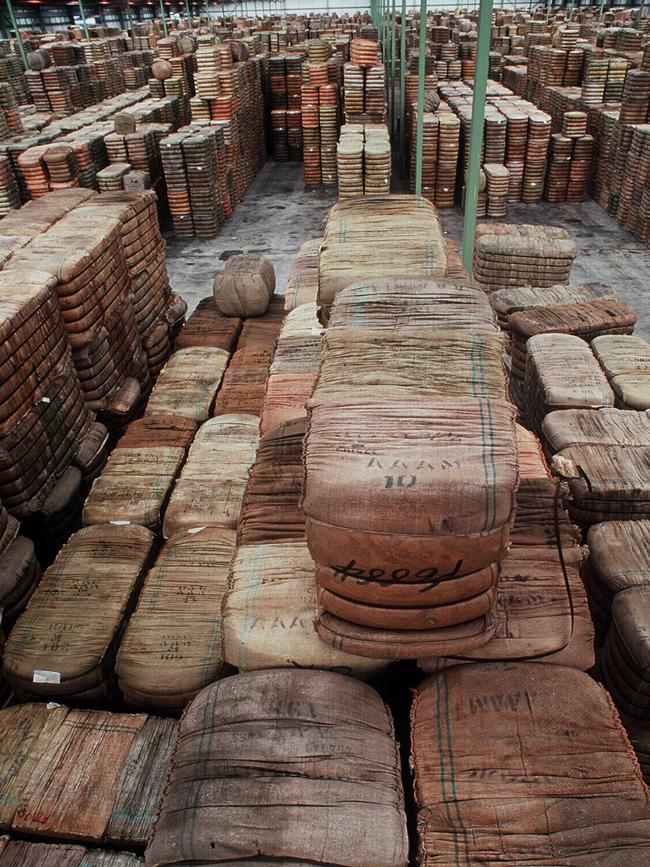

The wool mountain kept growing and growing as Australia refused to buckle to market realities and put a floor under the wool price. The taxpayer became the buyer of last resort.

As Donald Trump has now found out with Wall Street – fight the markets at your own peril, and as wool prices collapsed Australia was forced in a painful retreat.

It took more than a decade for Canberra to slowly offload all that warehoused wool, representing a double-whammy for farmers, given the very existence of the stockpile kept global prices depressed longer than needed with the ever present supply glut.

For wool farmers, what had been missing before the collapse of the reserve pricing scheme were the necessary pricing signals.

This would have given the farmers early warning that it was time to switch from wool to prime lamb, or even make a bet on crops. Instead, the wool rolled off the sheep's back year in, year out, and no one was buying, except the Australian taxpayer – and prices ultimately collapsed.

Wool and rare earths might be a world away, but they are markets that still operate under the laws of supply and demand.

The Albanese government has one eye on a coming round of tariff negotiations with Trump and wants to use this leverage as an election goodie through the promise of a $1.2bn reserve of critical minerals – essentially a stockpile.

This means Australia would have enough critical minerals on hand at any point in time that can be sold to friendly countries like the US or Japan when there is a global supply squeeze. It’s Trump’s trade fight with China that has turned up the rare earths threat.

Rare earths are a very big deal for business and geopolitics. These are a string of metals used in high-end electronics such as smartphones, chips and medical devices, through to heavy industrial applications. They are also increasingly used in defence industries, with hundreds of kilos of different elements used in the US-manufactured F-35 stealth fighter.

China controls as much as 90 per cent of the global supply of some rare earths and is prepared to use its market power.

This month, China slapped tighter conditions around the export of rare earths, as part of its targeted responses to Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs. As part of this, it was demanding guarantees some magnets wouldn’t be used in military hardware.

Under the ban were two key elements, dysprosium and terbium, the workhorses of modern technology. These two metals help regulate heat in high-performance magnets that are then used in applications in everything from turbines to rocket jets.

Like much on the campaign trail, a minerals stockpile is good on paper, but the plan falls apart under scrutiny.

The fatal flaw of the Albanese plan is that it is focused at the wrong end of the supply chain, with much of the effort seemingly put in to concentrate, rather than refined products.

To build out more refining capacity without the right long-term pricing signals is a recipe for pain down the track. It would also involve deep pockets to take China and its industrial grip on the supply chain head-on.

Then there’s the additional complication – as you would recall from high school science – that not all elements are the same. The heavier the element, the shorter the pre-refined shelf life before it decays. (Although both dysprosium and terbium are stable metals that do not exhibit any radioactivity or decay so storage is possible).

Ultimately, any government stockpiling key minerals as a hedge against China can send the wrong pricing signals to the market.

Iluka bump

It’s a distortion on prices and could encourage a flood of short-term production for some areas, adding to the notorious boom-and-bust cycle across critical minerals. Lithium has been the best example of this, with many projects being curtailed on the pricing slump, causing much pain and capital torched.

It could also see bigger players such as Lynas or Wesfarmers that have already stumped up the investment in refining capacity suddenly compete with a flood on rivals looking for a slice of the government contracts. Like the wool stockpile, the threat of surplus supply hitting markets in times of stress puts a ceiling on prices.

One big winner from the plan is Iluka, which is building a refinery in Western Australia to process rare earths, including neodymium and praseodymium, also needed for high-performance magnets.

These allow magnets to be much more powerful but smaller. These are used in defence systems, robotics, electric and hybrid vehicles. The Iluka plant is being mostly funded with a $1.6bn loan from Canberra. The plant is scheduled for commissioning from 2027 and Iluka has been looking for offtake partners rather than relying on spot markets. Now with the Albanese stockpile, it has just found one. It’s little wonder Iluka shares jumped as much as 5 per cent on Thursday.

Speaking to Sky News’ Ashley Gillon, Resources Minister Madeleine King said the planned stockpile would be considered a “national asset” to break the monopoly of supply from China, although acknowledged much of the detail needed to be worked through. It was clear from King’s comments the design was geopolitics-led rather than industry-led.

“This is an asset that will work in Australia’s interest for our own strategic purposes,” she said. “It’s really an important piece of the puzzle when we deal with other nations, be it Japan or Korea or the US.”

There are 31 minerals on the government’s critical minerals list, including lithium, nickel, praseodymium and terbium. What metals make it to the stockpile needs to be worked through, King said.

“Some (minerals) have more challenges at a particular time.”

Robot crush

The idea of a stockpile comes as Tesla boss and Trump confidant Elon Musk was bemoaning China’s global hold on the production of industrial magnets.

This has put yet another delay in Tesla’s long-promised production of a human-like robot. The motors of the arms in the so-called Optimus robots rely on magnets to help it move. Musk confirmed China hasn’t outright banned the exports, but has tightened export restrictions.

“When something is volume constrained, like an arm of the robot, then you want to try to make the motors as small as possible. We did design in permanent magnets for those motors, and those were affected by the supply chain (of) China requiring an export licence to send out any rare earth magnets,” Musk told a Tesla investor conference call this week.

“Hopefully, we’ll get a licence to use the rare earth magnets. China wants some assurances that these are not used for military purposes, which obviously they’re not. They’re just going into a humanoid robot.”

China is still exporting magnets, including 17,000 tonnes in the March quarter, according to brokerage Macquarie.

The better way to get more products into the supply chain is getting governments to remove friction in getting projects up and running. Australia has the head start with the key minerals in the ground, and pricing distortions won’t help producers commit more capital. What we don’t need is another wool stockpile.

Remember the wool stockpile? It towered like Australia’s own woollen tribute to the great pyramids, at one point it was sitting on more than 4 million bales.