House of Cards author Michael Dobbs talks Margaret Thatcher, Kevin Spacey, Ian Richardson

Michael Dobbs talks Thatcher, Spacey, Richardson, and how an FU to his ex-boss led to the sensational political thriller.

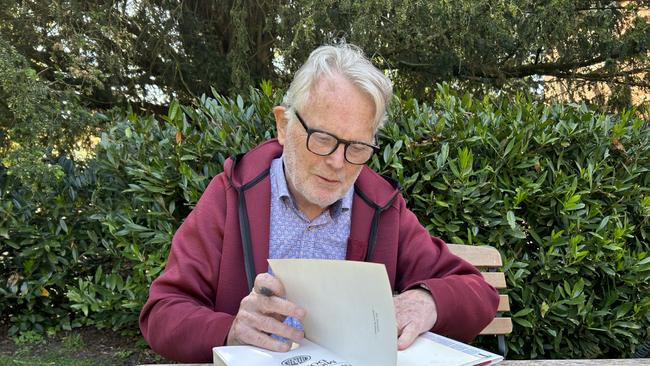

Dobbs, once dubbed Westminster’s “baby-faced hit man” during his time working for Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative party in the 1970s and ’80s, could not be more charming and unfailingly polite. He is a life affirmer, and brims with enthusiasm and enjoyment about this phase of living.

As we walk into the ancient cathedral city on this sunniest of English days, he talks engagingly about his family in Australia, renovations to his home outside Salisbury, new writing projects and being a life peer in the House of Lords while stopping to point out landmark sites and chat with people on the street.

His life changed dramatically during the 1987 election campaign when Margaret Thatcher, fearing the election was lost, sacked him as party chief of staff. Dobbs had been by her side, working for the party and campaign advertising agency Saatchi & Saatchi, since 1975. The Iron Lady did more than just sack him; he was publicly rebuked and humiliated.

“I really had been pretty brutally abused,” Dobbs recalls of the cabinet room execution in front of ministers.

“Having been in politics for so long, I had to find something else to do. Margaret rather insisted on it, so, and it hurt. It was a really big turning point in my life. And, yeah, I should have been in therapy.”

The therapy was a bottle of wine and pad and pencil. Dobbs escaped to Malta for a holiday. Sitting poolside, he scribbled “FU” on a notepad. It was a “f..k you” to Thatcher. He had been reading an underwhelming novel. As he doodled more, he realised he could do better. “FU” became Francis Urquhart. House of Cards was born in an act of catharsis.

“I’d never had any ideas of being a writer,” Dobbs says as we sit in an outdoor cafe. “I was reading a bestseller at the time, and I was hating it. I was going on about it and my wife turned around at me and said, ‘For god’s sake, stop going on about this bloody book. We are away on holiday for the first time in 2½ years and I’m here to enjoy myself, not listen to you going on. If you think you can do any better, for goodness sake, go and do it.’ ”

When House of Cards was published in 1989, it was a sensation.

The political thriller centres itself on the character of the Right Honourable Francis Ewan Urquhart, the chief whip, who we learn was ageing, bored and resentful but had not lost “his appetite for politics and power”. He was “tall and angular”, never warm, and sharply direct with people. He schemes with Machiavellian intensity to destroy careers and elevate his own.

The themes of ambition, deception, blackmail and betrayal, set against a political backdrop, are Shakespearean. It is essentially Julius Caesar, Dobbs says.

He recalls deputy prime minister Willie Whitelaw telling him after being fired “that woman will never fight another election”. The idea, then unbelievable, lodged. Dobbs also had spent a lot of time with the whips, learning what they covered up and exposed. He, too, had done tough things as chief of staff.

The response to the book and television series was overwhelming. Dobbs says through the years people have come up to him insisting that Urquhart is based on them, their pride never concealed. “No, it wasn’t you, I’m afraid,” he always says. The appearance of Urquhart, though, is based on Nicholas Ridley, another Thatcher-era minister.

The BBC dramatisation by Andrew Davies and starring Ian Richardson as Urquhart is compelling. Nothing surpasses it for political drama on screen. The series premiered as Thatcher was being forced out of office. It begins with Urquhart turning down her framed picture and saying to camera: “Nothing lasts forever. Even the longest, the most glittering reign, must come to an end someway.” Dobbs says “everybody thought I was brilliant” because it foretold Thatcher’s demise.

“God that’s him,” Dobbs recalls on first seeing Richardson, who would take on the iconic role. “A brilliant actor. We became friends. He was an absolute gentleman and I loved every minute of the experience with him.”

The series was so enthralling that Dobbs had to bring Urquhart back from the dead. When journalist Mattie Storin reveals his dishonourable and deadly deeds, he throws himself from the roof of the Palace of Westminster. Dobbs wrote two sequels – To Play the King (1992) and The Final Cut (1994) – also adapted by the BBC. Urquhart’s catchphrase “You might think that; I couldn’t possibly comment” became legend.

Netflix picked up the novels and transposed them to the US with Kevin Spacey portraying Francis Underwood in 2013. This series was also hugely popular. Dobbs says he fell out with the BBC’s treatment of his novels but remains proud to be associated with Netflix. The series concluded without Spacey, now facing charges for alleged sexual assault.

Dobbs says Spacey was an “absolutely brilliant actor” but they never got along personally. “We never had any close relationship,” Dobbs says. “I don’t think that I was his type of person at all in any way, and it showed. We fell out big time, before the public debacle.”

The books were informed by Dobbs’s experiences in journalism and politics. While studying for a masters and PhD at Tufts University in the US in the early to mid-1970s, Dobbs worked at The Boston Globe. He observed Richard Nixon become enveloped in Watergate. “All of this paranoia and anger that he had in him just spilled over and he destroyed himself,” Dobbs recalls. “It truly is Shakespearean.”

Thatcher had become Conservative Party leader in 1975. Dobbs recalls that few in her party or in the Labour government thought she would last long. They were patronising, condescending and misogynistic. He found her to be a tough, determined, obsessive leader who learnt quickly how to survive and succeed in politics.

“She put her neck on the line for what she believed in politically, her reputation, her career, indeed, even her life, because she thought that it was that important,” he recalls. “I found her inspirational and impossible – all wrapped up together. I learnt a great deal from her and I lasted with her on and off a very long time, longer than most.”

A conviction politician who was courageous and thrived on confrontation, Thatcher left an indelible mark on Britain. She is admired or loathed, forever a divisive rather than unifying leader, but still inspirational for many. Dobbs admires her leadership that lifted Britain “out of the mess it was in” despite their later fallout. He says the key to understanding her lies in an understanding of her sex.

“She had, for her entire life, from school onwards, been told that because she was a woman, she couldn’t do this, she couldn’t do that,” Dobbs says. “She couldn’t go to grammar school, she couldn’t go to Oxford, never get a proper job. She would never make it into parliament. She couldn’t be prime minister … she was obsessed with showing that they were wrong.”

He says Thatcher was a “tough woman” but “loved being treated as a woman”. She never tried to be a man in a man’s world. She also used her sexuality for political advantage. Men flirted with her and she enjoyed it. “People didn’t know how to argue with a strident woman, it was quite disarming,” he says. Thatcher, he notes, was not a feminist. “It’s up to them to show that they’ve got what it takes to follow me,” Dobbs says of her attitude towards other women.

Ahead of the 1987 election, Dobbs was made party chief of staff. He recalls asking a colleague what the job entailed.

“‘Well, lad,’ he said, ‘There comes a time in every war where those who are in charge of it require that somebody be taken out into the courtyard, put up against the wall and shot.’ He said, ‘Your job is to find the bodies until such time as you’ll be the body’,” Dobbs says, laughing. “He was absolutely right. So, it all ended in the horrible tears. But my goodness me, what an adventure it was.”

Dobbs now suspects Thatcher was suffering early onset dementia by 1987. “She was losing her patience,” he recalls. “She was an ageing woman in a hurry. And she was no longer running the government in the same way.” The illness “explains so much”, he says, and “makes it easy for me to accept”.

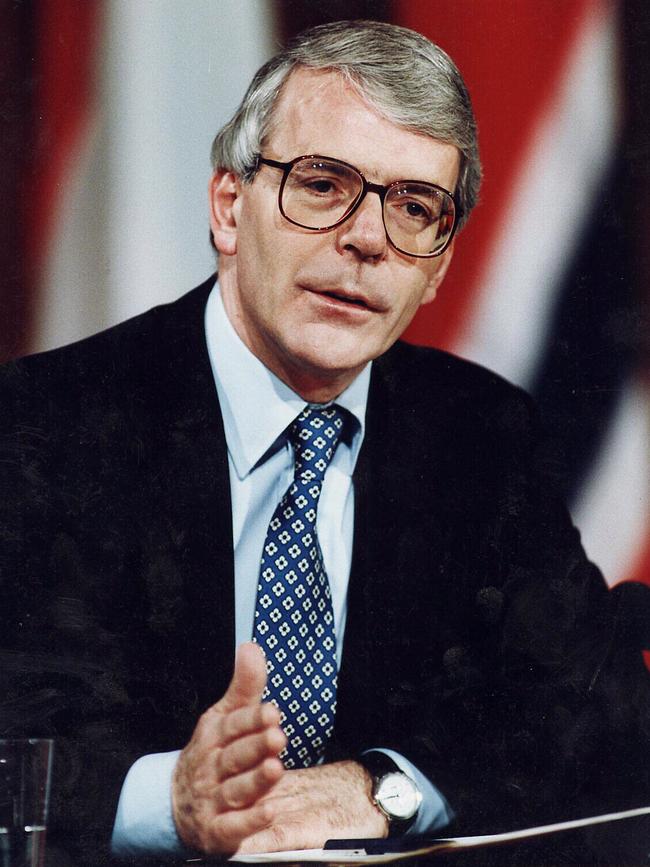

Flush with success from House of Cards, Dobbs returned to the Conservative fold when he became deputy party chairman under John Major, who had succeeded Thatcher and won the 1992 election. Dobbs liked Major and says voters found him to be decent, but argues he squandered his prime ministership.

“I get on much better with John than I ever did personally with Maggie,” he says. “But he didn’t have the same clear world view that she had. He took over after all those years in power. The voters weren’t quite sure about him, but they gave him another five years in office and it was a disaster. We ended up getting absolutely crushed at the polls.”

David Cameron elevated Dobbs to the House of Lords in 2010. He is kind to Cameron, whom he first met when the future prime minister was a teenager, and praises his skill at managing a coalition government.

But he says while Cameron always aspired to be prime minister, he lacked Thatcher’s energy and determination. Dobbs says Cameron should have continued rather than resign following the Brexit vote in 2016.

He remembers telling “Dave” about the fate of prime ministers: “The bastards will get you in the end. Every prime minister, unlike a president of the US, is hacked, chopped, stabbed to death, dragged out of office, leaving their fingernails in the carpet at No.10, because they never know when to go.” The same fate, after all, came for Urquhart.

In recent years, Dobbs has battled cancer and an inner ear infection that robbed him of balance. He wobbled on the walk into Salisbury and joked he is right at home in the tearoom of the House of Lords. He enjoys the friendship and debate with fellow peers as they lament the lack of respect for institutions and politicians, a crusading media, a post-truth world and cancel culture.

Dobbs has written many novels since House of Cards, including a series centred on MP Tom Goodfellowe and another on Winston Churchill, beginning with Winston’s War (2002). He has not written much in the past decade due to health problems but now has several book, theatre and television projects he is enthused about, including a Churchill play and a House of Cards sequel.

He says he loves researching, observing others and situations, and using it on the page. Two hours after we meet, Dobbs returns to that almost literary scene.

“As we met at the station, you were making things up about me,” he says. “You were using your journalist’s instincts to decide what sort of person I was. That view changes as you get to know me better, but that’s what you and that’s what novelists do.”

Dobbs is thankful to Thatcher. He thought his world had ended when she cruelly and viciously fired him, but it opened up a new vista of writing and speaking, delivering “fame and fortune”, and a renewed political career.

“I have these lovely moments every day when I’m thinking about the next concept where new ideas happen, and that’s what keeps me going,” he says. “I had absolutely no idea that writing was going to change the rest of my life, which it has done. And I owe it all to being beaten up by Maggie.”

When Michael Dobbs suggested I board a train at Waterloo station and he would meet me at Salisbury, about 90 minutes outside London, and take me to an undisclosed location for a sit-down interview, I imagined this could be a fateful scene from his House of Cards series of political novels.