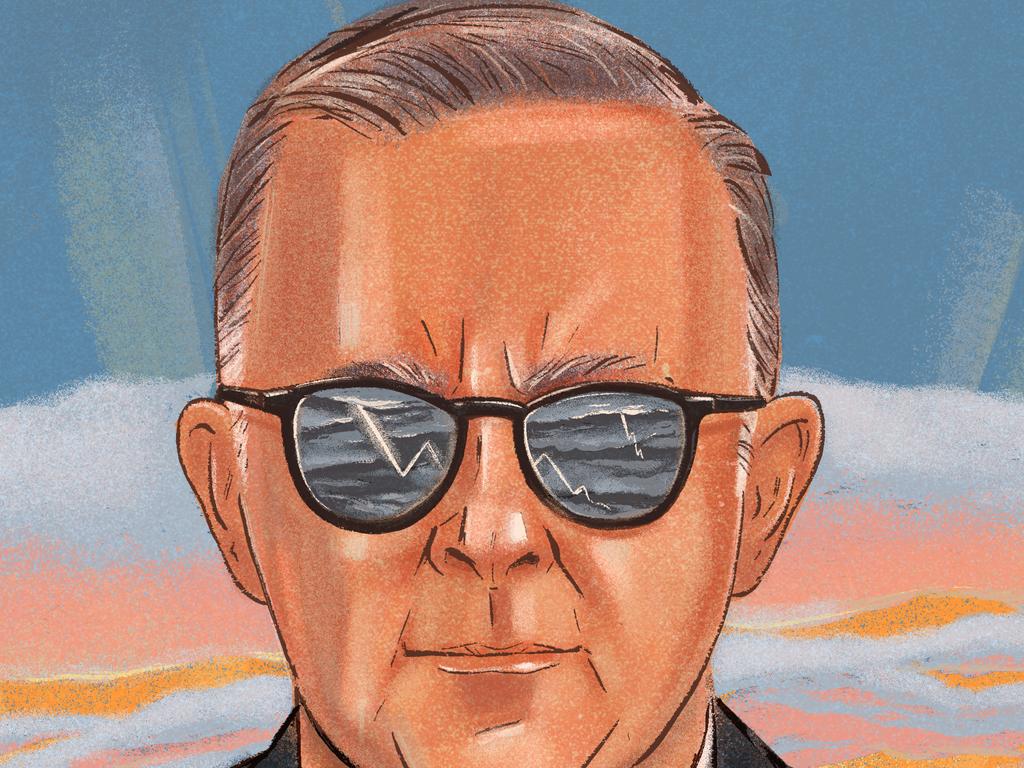

Election 2022: How Scott Morrison and the Liberals knew party was over

The mood at the Liberal Party’s election-day after-party was not exactly what you would have expected following a loss of such catastrophic proportions.

Late in the evening on Saturday, May 21, Jenny Morrison was dancing with friends in a private room at the Fullerton Hotel in Sydney’s CBD.

Some say she was beaming. Whether it was simply relief from the election campaign finally being over or the joy of knowing she now had her husband back after three grinding years is hard to say.

Whatever it was, the mood at the Liberal Party’s election-day after-party was not exactly what you would have expected following a loss of such catastrophic proportions.

It certainly wasn’t buoyant but it was no funeral dirge either.

To be sure, there were tears. People were emotional, including Scott Morrison’s chief of staff, John Kunkel. Morrison himself was subdued. But he was far from a downcast figure, according to those in the room.

To some, it appeared the weight of the world had been lifted from his exhausted shoulders.

In the room that night were about 100 people. John Howard was there, as were other Liberal heavyweights, family friends, their partners and staff from Morrison’s office as well as key people from the campaign team.

Morrison got up there shortly after 11pm and addressed the room. He was neither downtrodden nor upbeat.

He had given his concession speech downstairs only minutes earlier. Now it was time to talk to his inner circle and close friends.

He told his people they should be proud of what they had achieved over the last 3½ years.

In private conversations, he would say that history would remember their time in office well.

Kunkel also spoke to the room, choking back tears, as did Andrew Hirst, the Liberal Party’s federal director and campaign manager.

They had been through the most intense period of government since the Second World War – a pandemic punctuated by natural disasters – only to be thrown out of office having saved the economy and saved lives.

But it was Jenny who stole the room. She thanked everyone. A picture of grace and gratitude, she had made a point of hugging almost everyone in the room, and making special mention of the Australian Federal Police, who had shadowed her family since Morrison got the top job.

She joked that the PM’s next job was to now do the school run.

It was a different vibe than that of a couple of hours earlier when the realisation had struck Morrison that the Coalition had just lost the election. That moment came around 8.30pm when the numbers from Western Australia started rolling in. The prime minister was still at Kirribilli House with his senior staff and family.

He had conducted these affairs somewhat differently to past leaders. Unlike Howard, for example, who kept election night vigils to a handful of advisers, there were several dozen people roaming the twin-gabled gothic mansion that Saturday afternoon.

Occupying the east-facing study were Morrison and his senior personnel and closest friends. Kunkel, private secretary Yaron Finkelstein, executive officer Nico Louw and communications director Andrew Carswell were fixated on their phones and tablets watching the count.

Former Howard adviser David Gazard, Scott Briggs, a former Liberal Party official and businessman, and Adrian Harrington, the property tycoon, were also in the room. Other friends and family would walk in and out of the study through the early evening in what was a relatively relaxed atmosphere. The kitchen staff put on rounds of beef party patties – the 2019 chicken pieces hadn’t received rave reviews. But no one was really hungry.

Ever the optimist

Morrison had remained optimistic until the end. “In the first hour, there were those swings in regional areas, and people were thinking it was 2019 all over again,” said one insider. “There was definitely a feeling that this looked like a repeat of 2019.”

But as the night wore on the mood began to darken.

“It looked like Labor were going to lose in minority, then it began to shift,” the insider said.

When seats in Western Australia began to fall like dominoes, Morrison kicked everyone out of the study. He told Kunkel, Finklestein and Carswell to stay.

The four men then began working on his concession speech.

Shortly before 10pm, Morrison prepared to leave Kirribilli for the city. He had called Anthony Albanese to concede defeat. But not before he told friends and colleagues that while his time had ended, there were achievements they had secured in government that no one could take away from them.

At the Fullerton, the Liberal Party had secured multiple rooms for the night, including the main function room on the ground floor. Upstairs, and down the hall from the PM’s room, was a campaign war room with banks of computer screens displaying the numbers as they were coming in.

This was occupied by a tight group including Hirst, party pollster Mike Turner (Crosby Textor), David Hughes, a senior researcher, Guy Creighton, head of the campaign media team, and Isaac Levido, the Australian ex-Crosby Textor political strategist who had run UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s successful 2019 election campaign.

“We knew it was over as soon as the numbers from Western Australia started coming in,” said one senior Liberal source in the room. “The room was pretty flat at that stage.”

Morrison had still been hopeful the morning of polling day, with the party’s tracking showing the gap had narrowed over the course of the campaign. Others in the Liberal camp weren’t as confident.

Prior to the April budget, according to a senior liberal source, internal polling showed the government was in serious trouble. It was on track to lose up to 30 seats. In other words, a wipe-out.

What had given Morrison cause for optimism was the gradual narrowing of the numbers according to their tracking of 20 key seats. While the published polls were consistently pointing to a considerable loss, the internal polls began closing from budget day right up until election day. “Throughout the whole campaign it appeared to be coming back our way,” said another senior insider. “It stalled over Easter but the trajectory from the budget to polling day was definitely tightening.”

Shock results

But no polling, however sophisticated, could account for what was happening in the so called “teal” seats – the Liberal moderate-held electorates in inner-city Sydney and Melbourne that turned so violently against the government.

Turner had conceded he was concerned about these seats because they were so hard to get a read on. “We had to run two campaigns,” said another senior campaign source. “One against Albo, another fighting a teal campaign on the ground.”

They admitted trying to get up negative news stories on the candidates, revealing their true colours, was made difficult because few had historic public profiles that could trip them up.

This was also true of Labor candidates, with a concerted effort over the past few years to clean up their social media profiles to limit the ability of the “dirt units” to dig up past indiscretions.

“The teal seats were almost impossible to poll,” the insider said.

“CHQ was conscious that they had to hit these teals but they were limited to what they could do.

“The best thing we could do at a national level was to scare people about a hung parliament.”

Campaign headquarters was based in an office in Brisbane, as it was in the previous election. It was located in a nondescript building on Coronation Drive, on the Brisbane River, with staff housed in the nearby Cosmo apartments.

A barber located just around the corner got a good workout, as did several early opening baristas. “I reckon every bloke in CHQ ended up getting a haircut at some stage,” said a CHQ operative. “They did a roaring trade.”

The first call every morning of the six-week campaign was logged at 5.30am with key officials and the PM. CHQ operatives on this call consisted of Hirst, Turner and the party’s deputy director, Simon Berger, as well as Kane Silom, an experienced campaign operative and communications director for Josh Frydenberg. At 6.15am, this was extended to a broader conversation before a 6.30 phone hook-up with the leadership group and CHQ.

The leadership group included Morrison, Barnaby Joyce, Simon Birmingham, Michaelia Cash and Peter Dutton as the core.

There were other staff on the calls. But the polling wasn’t shared. It was kept very tight.

Apart from the PM, who had the actual numbers, the general polling guidance from Turner to the leadership group was on messaging. What was working for them on a daily basis, and what wasn’t. Very few had access to the actual numbers.

Despite this, the mood was optimistic in the first couple of weeks, buoyed by the gaffes Albanese made. As the campaign wore on, there was a feeling that the Labor leader’s missteps simply became factored in. In other words, the more mistakes he made, the less impact they had.

On the core equities, however, the economy and national security, it was positive for the Coalition. But no polling could account for the teals.

Critical factors

There was no doubt the race was tightening over the campaign. But they were under no illusion that unlike the blank canvas of 2019, this time they were working with a prime minister who had become deeply unpopular.

There was a view among some that the Victorian and NSW lockdowns in mid-2021 had cemented a downward spiral for Morrison that was unrecoverable.

Despite entreaties late last year from a couple of nervous moderate Liberal MPs, treasurer Josh Frydenberg never seriously entertained the idea of challenging Morrison for the leadership. He would remain loyal to the end, despite that end becoming his own after losing his seat.

According to one senior Liberal operative, the bungled rollout of the rapid antigen tests over summer was the final straw for Morrison. From there, it was a long road back.

So much had been put into the campaign that no one had a view to what would come next, should they lose.

In an instant, it was all over.

When asked on Saturday, May 21 when the result was obvious, what he planned to do, Morrison is said to have told a friend his first plan was to sleep.

For a man like Morrison, whose faith is everything, it wasn’t as if it were the end of the world. He was genuinely satisfied he had run as hard as he could. He left nothing on the field and believed he’d left a strong legacy.

“He will find another calling,” said a friend.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout