Scott Morrison cast a defiant figure on Wednesday as the government used its superior numbers to censure a former prime minister for the first time in the parliament’s history.

And the Coalition’s troops rallied behind him. Mostly.

Peter Dutton ensured the Coalition partyroom – bar two - backed their former leader, mindful of what the Labor Party had done to Kevin Rudd, and itself, in tearing down one of its own.

Few of Morrison’s colleagues agree with what he did, but for the Opposition Leader to have abandoned the former leader would have been to delegitimise the Coalition’s record of government, trash the Liberal brand further and consign its achievements in the pandemic to the dustbin of history.

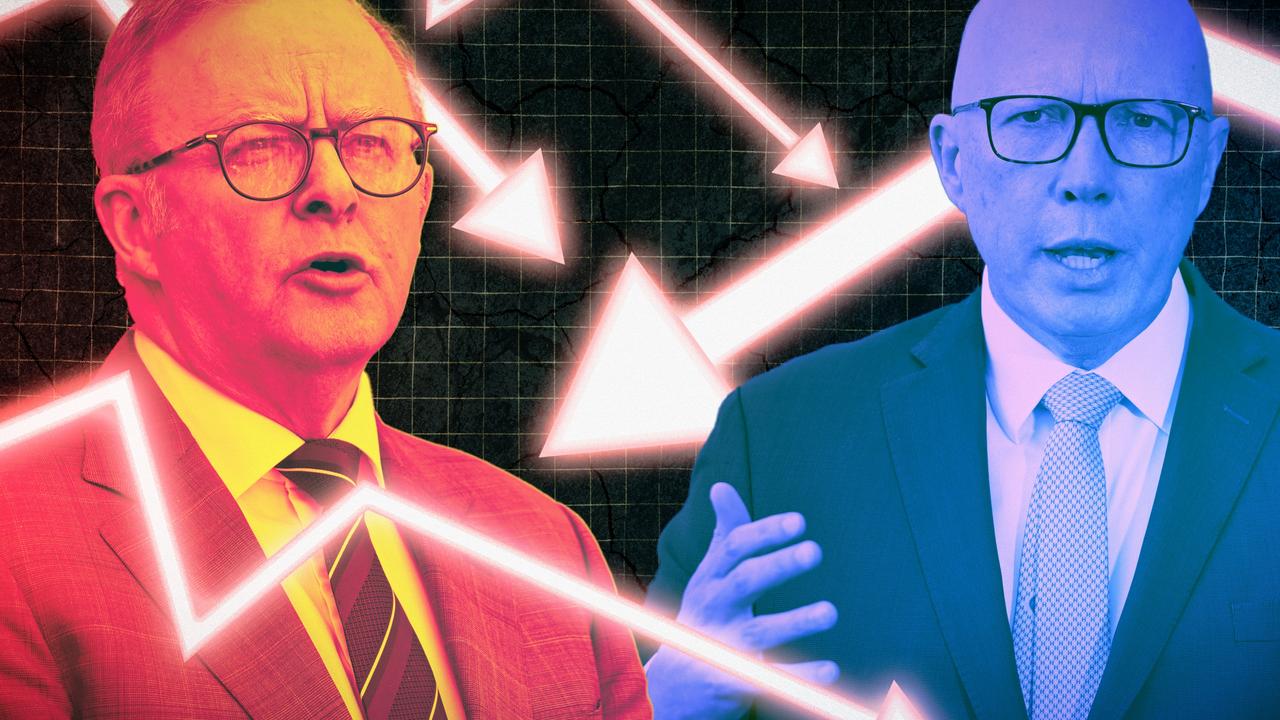

For Anthony Albanese, this was the final chapter in a long pursuit of Morrison personally.

In opposition, he built his campaign around Morrison as a flawed leader. The post-election controversy over multiple ministries ensured he was going to keep hunting him once in government.

The Prime Minister was careful to avoid the piercing mockery that has characterised the prosecution until now, in the likely knowledge that overreach could eventually blunt the attack.

For Morrison’s part, he apologised to colleagues to whom he caused offence by his actions, which he reminded the house were lawful, but retreated from an acknowledgment that he owed a broader apology to the nation – or parliament - demanded by Labor.

The government, and some of Morrison’s colleagues privately and publicly, maintain that his explanations still defy credulity.

Morrison said he would refuse to submit to political retribution, maintaining that while at least some of his actions he now agreed had been unnecessary, he believed a more substantive argument prevailed.

This was that he had acted in the national interest, at least in the first two self-appointed secret ministries of health and finance.

These were actions taken that he would never resile from, owing to what he said were extraordinary decisions made during extraordinary times and judged now in the safety of hindsight.

He used his almost 30 minutes to speak against the government’s censure motion – following a deal with Labor to allow him extra time - as a platform to defend his legacy as prime minister and list the achievements of the former government’s management of the pandemic.

Manager of opposition business Paul Fletcher led the defence of Morrison, arguing that it was the government that was abusing its power by abandoning long-standing conventions. Censure motions by convention are used to hold ministers to account rather than opposition backbenchers.

“This censure motion makes no practical difference, it is … simply a political exercise in seeking to damage the reputation and standing of the former Liberal prime minister,” Fletcher said.

Albanese has already reaped the political dividend that he was hoping for.

Continuing to lay the boot in could carry its own political risk while his government grapples with a cost of living and energy price crisis.

Nevertheless, Wednesday’s events, which consumed three hours of parliamentary debate, are unlikely to bring an end to Labor’s pursuit of Morrison.

This month, the former Liberal party leader will appear before the royal commission into robodebt and a new cycle of legacy trashing of the Coalition will begin.