A town pays the price of grog and punting

The end of the Coalition-era cashless debit card is dividing a remote South Australian community.

It’s 10.10am on Thursday in Ceduna and Anangu elder Maureen Smart is quietly outlining her case against Australia’s cashless welfare card.

In the neighbouring streets of the remote South Australian town, a few dozen Indigenous people from the Yalata and Oak Valley – dry communities deep in the outback – are wandering around, most quietly embracing the beginning of the end of quarantined welfare.

For 65-year-old Ms Smart, from Yalata near the West Australian border, her hostility is all very simple. For her, the card has been too hard to use.

“It’s the technology, it’s no good for the elders in the remote communities,’’ she says.

“I am not a drinker, we don’t drink. I thought it was for the alcoholic people.”

Sitting next to her is Russell Bryant, a pastor from Yalata, who is happy with the card, using it to transfer money to and from his two adult daughters, managing his financial affairs while living at the head of the Great Australian Bight, where some of the people are descended from Maralinga country.

“My girls look after me; I look after them,’’ Mr Bryant said.

The story of the cashless welfare card of is one of deep ambiguity and divisions, of strongly held views that the Coalition-era policy has worked and equally strident opposition to controls on alcohol and gambling spending among the disadvantaged.

While police are reporting significant drop-off in some crimes in the area, the scourge of domestic violence remains, with a growth in reported cases. However, officers believe the amount of offending has not necessarily climbed but confidence to alert authorities has.

Ceduna Council chief executive Geoffrey Moffatt, a backer of the card and other support measures such as alcohol restrictions, warns that when the mandated welfare system is shut down there could be a return to what many in the town believe were the bad old days of rampant violence, alcohol and gambling abuse that often poured onto the foreshore that overlooks Murat Bay.

Many of the hard-core drinkers arrive in Ceduna from the dry communities hundreds of kilometres away in the desert, some sleeping rough, others imperilling their safety as they walk onto major roads at night.

Mr Moffatt said that, in the past, violence was ubiquitous and road dangers were persistent.

“We expect a return to all of that,’’ he said.

So has the card worked?

“Immensely successful,” he says, adding that it was the suite of support measures such as alcohol restrictions that also helped curb the social dysfunction.

Former Ceduna mayor Allan Suter, who was on the ground in 2016 when the card was introduced in a trial, is a big supporter of the reform but also a realist who said the strategy was never going to completely stop the inebriated.

“It didn’t stop it in its tracks; it slowed it down,” Mr Suter said.

He added that, before the card, bashings, molestations and other offences were common.

“Before the card, most nights we had groups of young kids as young as six roaming the streets all night,” he said.

On the question of rolling nights of violent crime, Mr Suter said: “That absolutely stopped.”

Ceduna is almost dead centre between Sydney and Perth – 2000km either way; a small town 490km from the WA border that is better known for its sharks and oysters than incendiary national political debate.

The town of 3400 people has rare southern Australian beauty but also a bleak history of violence and alcohol-fuelled offending, exacerbated by the town’s isolation, proximity to several isolated Indigenous communities and the honeypot effect of being a large transcontinental parking bay for 500,000 trucks a year.

The new federal Labor government will scrap the mandated debit cards, citing a critical report by the Australian National Audit Office that found the Department of Social Services had not been able to show the program was meeting its objectives.

Superintendent Paul Bahr of SA Police said statistics showed a general decline in victim-based crime in Ceduna over the past year of about 16 per cent, with assaults down by about 13 per cent.

Between 2014-15 and 2017-18, victim-reported crime fell by about 32 per cent, while the past two years of Covid have meant that gathering data can be problematic because of changes in people movement.

“Ostensibly, Ceduna’s crime issues are no different from those of any other regional (or metro for that matter) community,” Mr Bahr said. “Like all communities, there have been a growing number of reports related to domestic abuse, the growth in which is more related to greater community confidence in police to respond to these incidents rather than an actual increase in prevalence. It remains an issue, not only for Ceduna but the entire country.”

The Weekend Australian spoke to about a dozen card users in the town. The overwhelming majority were opposed to a system they said was hard to manage, and open to theft from family members and others.

It remains mystifying to some. Outside the Ceduna courthouse, Samantha Woods from neighbouring Thevenard is sitting in the sun with her three-year-old daughter Janet and a group of other kindred spirits.

“I don’t really like it,” Ms Woods said. “People are stealing our money. They use people’s accounts online. I had three people steal my money.”

With a tradition of sharing among family and friends, people said they would wake up in the morning to find that someone had drained their card of cash.

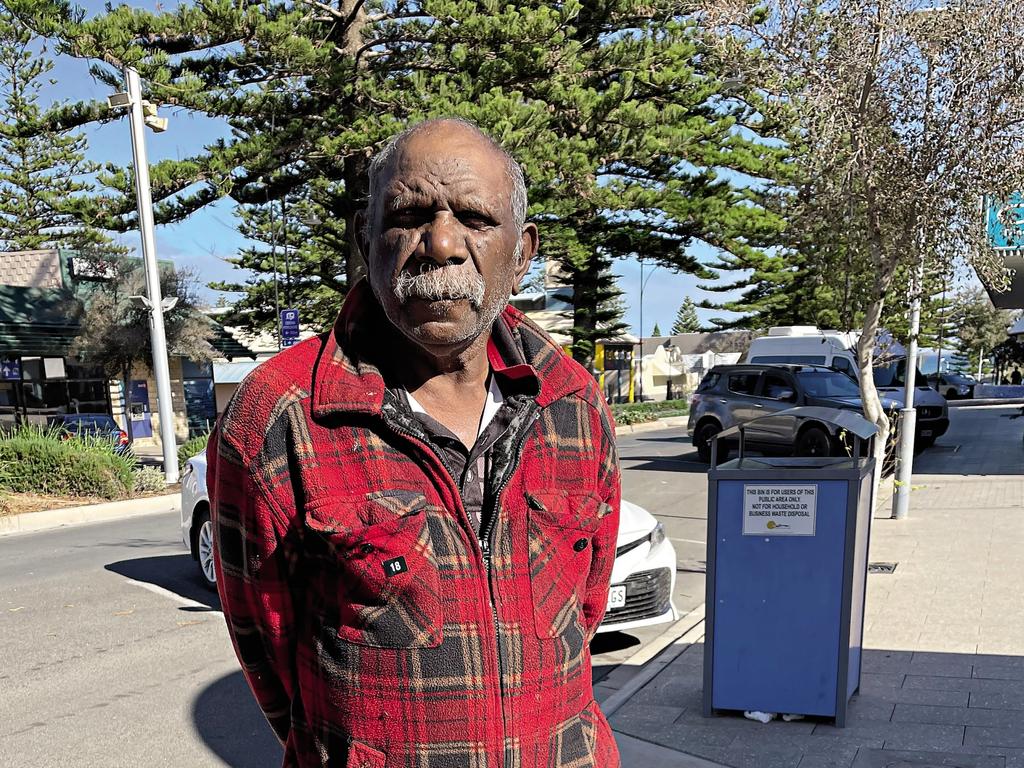

Greg Peters, 54, from Yalata, said he had more than $500 in his account on Wednesday and was saving to pay for his driver’s licence test but discovered the account had been drained.

“I went to the shop today – the money’s not there. It’s declined,” Mr Peters said.

The cashless debit card quarantined 80 per cent of working age recipients’ income support payments in selected trial sites, starting in 2016 in Ceduna. The quarantined cash could not be spent on alcohol or gambling nor to withdraw cash, while 20 per cent of support money went into the individuals’ bank accounts. About 75 per cent in the Ceduna trial were Indigenous, with trials also in WA, the Northern Territory and Queensland.

People have found their way around the restrictions, such as selling their cards for cash for below value and buying and pawning goods. The money is then used to drink or gamble.

Welfare worker Michele Jacobsen, who has been worried about the scheme’s complexities, said: “In my opinion, it didn’t evolve when problems were identified. It definitely had merit for people who suffered from the identified issues.”

But for those with digital literacy challenges, or no access to the internet, the card had its limitations. “It’s hard for those who don’t have access to digital instruments,’’ Ms Jacobsen said.

Ceduna is heavily supported by the taxpayer, a rich layer of bureaucracy cloaked over a town that Labor’s Families and Social Services Minister Amanda Rishworth plans to visit within weeks. Ms Rishworth is not opposed to voluntary managed welfare but says any engagement needs to be supported by the communities.

She said numerous investigations had failed to prove the worth of the Coalition card and any welfare management needed to be driven by the people most affected, not forced on them.

“We want that to come from community,” Ms Rishworth said.

There is a belief in the alcohol industry that scrapping the card will not change much.

No one wants to talk publicly but one leader said there was an insatiable drive by some drinkers to find a way to feed their habit. The enthusiasm is so great that people drive to Ceduna from hundreds and hundreds of kilometres away just to buy a hangover.