Time to get rid of Indigenous reconciliation police

The separatist spirit of the voice to parliament lives on in thousands of the nation’s corporate action plans.

When Indigenous elder Marcia Langton said no Indigenous person, including her, would deliver a welcome to country if Australians voted No to the voice, the floodgates opened to lingering concerns about whether a welcome to country divided us or united us. We discovered that many Australians believed it was the former, and had grown tired of receiving mini-lectures before meetings, sporting events, school assemblies and other gatherings.

Another issue crying out for sunlight is embedded inside most Australian companies, especially the biggest ones, along with government departments, not-for-profits and other groups. There you will find a Reconciliation Action Plan. And behind this “RAP”, as they are colloquially called, is one single organisation – Reconciliation Australia.

Reconciliation Australia tells these groups how to run their Indigenous outreach programs. Within RA and the bodies that unthinkingly do RA’s bidding with their RAPs, there is a shocking misreading of mainstream Australian values. Though the referendum proposal failed, the voice’s radical separatist spirit lives on in the RAPs of thousands of groups across the country. Given that ignores the memo sent by voters on October 14 last year, it’s time we asked whether RA, and RAPs, should be abolished.

The referendum result shows that Australians overwhelmingly believe in a single sovereign Australia in which we all have equal civic rights.

At the same time, Australians have enormous goodwill for Indigenous Australians, especially those suffering disadvantage. The country has devoted vast amounts of time, money and effort to practical measures to improve the lives of Indigenous people, and we are overwhelmingly happy to devote more to such practical endeavours.

However, the latest Closing the Gap report shows that RA and the 2700 RAPs inside Australian organisations have failed to shift the needle. There are poorer outcomes in early childhood development, increased numbers of Indigenous people in prison and more children in out-of-home care, as well as more Indigenous suicides.

Life expectancy gaps are not on track, nor are school completion rates, or employment or training or tertiary education.

That Closing the Gap targets are not being met is not from lack of care among mainstream Australians. It’s down to something else.

Reconciliation is one of those words that sounds nice. But what if this word, reconciliation, has become camouflage for holding tight to a set of policies that continually fail Indigenous people? What if RA is nothing more than a shakedown racket, playing on institutional anxiety and laziness to instil in those same institutions across the country a radical rights-based agenda that has patently already failed generations of disadvantaged Indigenous people?

RA enjoys monopoly power. Just about every major company or other group wanting to signal to the rest of the country that its leaders and workers believe in reconciliation drafts a Reconciliation Action Plan agreed with RA.

Once that’s done, they will be applauded by RA for formalising their commitment to reconciliation and can parade as moral corporate citizens. Many will be at Reconciliation Australia’s gala dinner next month in Brisbane.

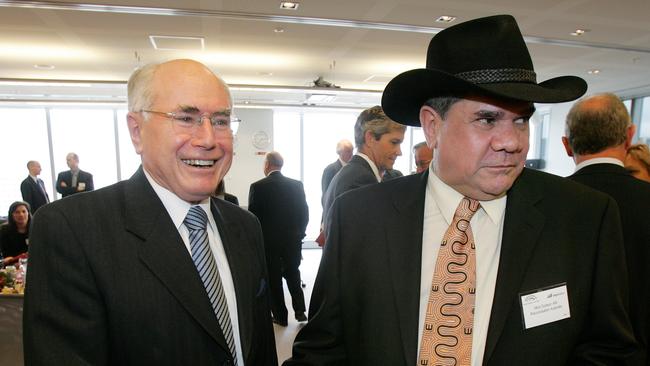

In 2006, prime minister John Howard launched the Reconciliation Action Plan program with professor Mick Dodson to encourage companies and other groups to effect practical solutions for Indigenous Australians. Since then, it seems that RA and its soldiers inside the environment, social and governance departments of big corporations have turned reconciliation into a covert pursuit of a ’70s-style separatist rights agenda.

What follows is hard to say and may be harder for some to hear. The focus of Indigenous activists on reconciliation and self-determination have set back the lives of the most disadvantaged Indigenous people. These are big amorphous words used by elites in the Indigenous industry – by groups such as Reconciliation Australia – to capture demands made by Indigenous groups.

And the model of modern identity politics means that when a victim group makes demands, the oppressor group must say yes because, as Damien Freeman said in this newspaper recently when explaining the voice agenda, who are the oppressors to question what victims demand?

This dismal model has certainly delivered good outcomes for elites in the Indigenous rights industry – they work in our law schools, sit on advisory committees, host radio programs, deliver speeches and fill the board of RA. The other consequence of identity politics has been to entrench even further into our body politic a rights agenda, giving short shrift to responsibilities.

Reconciliation Australia is a prime example. This not-for-profit entity is primarily funded by the federal government (through the National Indigenous Australians Agency) and various BHP entities. Its funding pie of about $10m is neither here nor there.

RA’s influence comes in controlling and giving its imprimatur to RAPs, and emphasising self-determination for Indigenous peoples. About 2700 groups have a RAP. That includes every significant Australian company – BHP, of course, but also the big banks, Coles and Woolworths, and the rest of the ASX 100, as well as the pre-eminent professional legal and accounting firms, government departments, not-for-profit entities, governmental agencies and other groups. RA offers four levels of RAP, each more activist than the former.

Many companies have the two highest levels – called Stretch and Elevate – which, according to the website, “can only be done in careful consultation with RA” due to the “specific requirements, expectations and processes”.

RA tells would-be RAP applicants that after they have paid their RAP registration fee, they will draft their RAP using one of RA’s templates, submit it to RA and “expect a minimum of 2 to 3 rounds of feedback” before RA will conditionally endorse it.

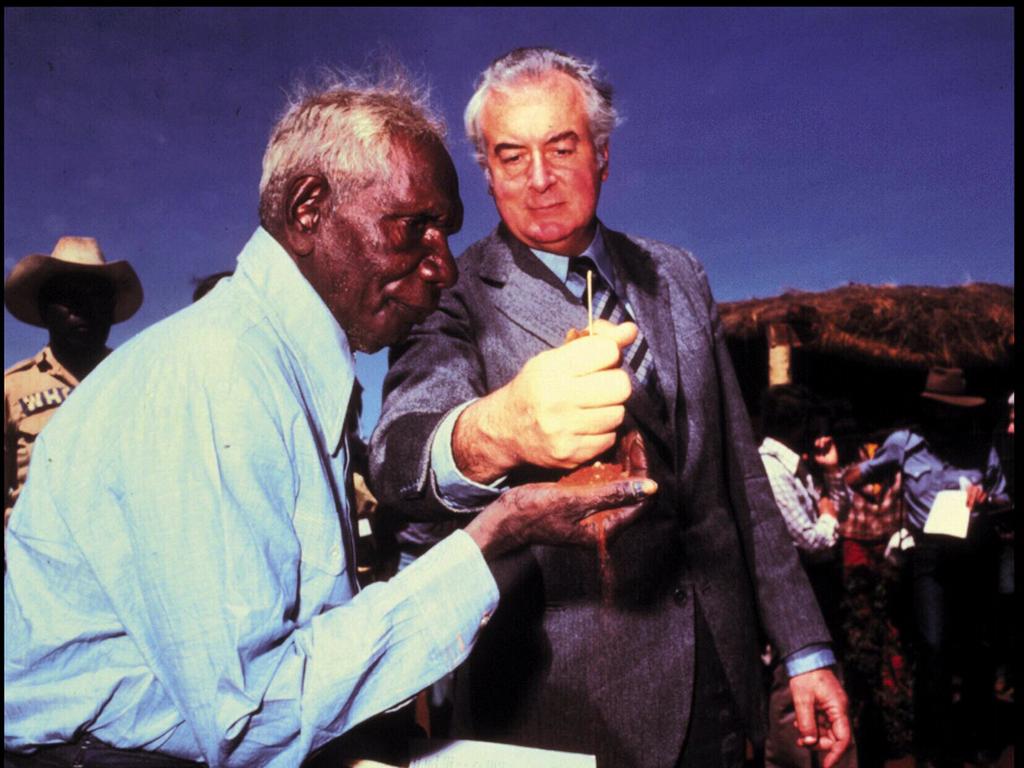

Given they are sourced from an RA template, it’s no surprise most RAPs look the same and embody principles peddled by RA from the separatist era more than 50 years ago when Gough Whitlam endorsed the UN’s International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights in 1972.

That UN instrument, applicable to every person equally, was overtaken in 2007 by the radical UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, or UNDRIP.

As RA chief executive Karen Mundine said to a 2023 parliamentary committee looking at incorporating UNDRIP into Australian law, RA’s Reconciliation Action Plan program “has been informed by a strong commitment to self-determination, drawing on the principles of UNDRIP”. According to Mundine, the organisations with RAPs “are committed to actions to progress reconciliation and embed the principles of UNDRIP in the policies, governance and practices of those organisations”. How many board members of big Australian companies realise that their RAP embeds the UNDRIP principles in their organisation?

UNDRIP is part of that UN phenomenon where the world’s activists for a particular cause design a “one size fits all” revolutionary charter that is often grossly inappropriate for many countries.

There may be countries and indigenous peoples for whom UNDRIP, or parts of it, makes sense. Australia is not one of them.

Our federal parliament has not incorporated UNDRIP into domestic law and could never do so because it is comprehensively inconsistent with Australian law and our political framework. Even a recent Labor-Greens dominated parliamentary committee stopped short of recommending it be made binding.

For example, article three of UNDRIP provides that by virtue of the right to self-determination, Indigenous people must “freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development”.

Article four says self-determination includes “the right to autonomy or self-government in matters relating to their internal and local affairs, as well as ways and means for financing their autonomous functions”.

Under our Constitution every Australian has equal rights, but this UN document clearly gives special rights to indigenous people. How does that work in practice when a company or other group endorses UNDRIP?

Take Coles, for example. Its RAP prominently features UNDRIP and says the supermarket recognises the declaration’s principles and will explore how to apply them within its operations.

Did executive and board members at Coles take some time out from thinking up clever pricing strategies to read the details of UNDRIP before signing off on the company RAP? Is Coles supporting self-governing states for Indigenous groups?

Article 14 of UNDRIP demands that “Indigenous peoples have the right to establish and control their educational systems”. Is Coles demanding a separate Indigenous school system? What about the fundamental responsibility of parents to ensure their children go to school?

How many chief executives and board members of other companies and groups understand that their RAP is a Trojan horse for a rights-based agenda that has failed generations of the most disadvantaged Indigenous Australians, especially women and children?

Or do companies sign up to RAPs without proper board scrutiny? It’s entirely possible the ESG department tells the chief executive that their company needs a RAP to be a good corporate citizen and, hey presto, a RAP – largely dictated and overseen by RA – is born.

That’s not to say all things companies and other groups commit to in a RAP are divisive or inappropriate. Coles deserves credit for supporting Aboriginal health service The Purple House, for donations of food and groceries to remote Aboriginal communities and for its training and recruitment of Indigenous young people.

But corporations could, and should, deliver all these steps to practical reconciliation without linking them inextricably to what appears to be the inflammatory separatist agenda of Reconciliation Australia.

The separatist attacks on Australian sovereignty are undoubtedly the worst features of the corporate RAPs sponsored by RA because they go to the heart of our cohesion as a society and a polity.

But plenty of other features in RAPs surely irk mainstream Australians to varying degrees. Endless claims that the land we live and work on is Indigenous land – even if it’s located in Pitt Street or Collins Street, are ubiquitous in RAPs and a constant feature of the welcomes to country we are forced to endure.

Indeed, it’s the compulsion behind RAPs, similar to how groups foisted the voice on workers, customers and other stakeholders, that will cause division.

The more aggressive corporations make no apology for their coercion. KPMG (some will say, who else) actually brags that in 2021 its national executive committee decided that Indigenous cultural awareness training would become mandatory for all staff and partners because attendance at voluntary training fell short of targets. This is terribly counter-productive. Compulsion is not even close to what reconciliation should be about.

The unforgivable shame is that by swallowing the four RAP flavours of RA’s Kool-Aid, big Australian companies, government bodies and other groups are taking the lazy and irresponsible path.

By outsourcing reconciliation to RA, Australia’s biggest companies have turned RA into the nation’s reconciliation policeman. That allows RA to guarantee that reconciliation and self-determination are far more wedded to rights agendas than practical outcomes, let alone responsibilities.

The biggest beneficiaries of this reconciliation racket are those Indigenous elites who give reconciliation directives, provide cultural training courses, sit on boards of groups such as RA, deliver welcomes to country, advise companies on how to draft a RAP and trot off to international gatherings to talk about self-determination.

How this provides any help to an Indigenous child in a violent family who hasn’t been to school for more than 100 days, has a mum who’s addicted to grog and an absent father is not obvious.

Companies and other groups don’t need RA. Forget the RA model of re-education cultural training camps in the workplace. As working adults, we can read and learn for ourselves.

If all companies, especially our biggest ones, got rid of their RAPs and instead focused on practical and generous steps towards reconciliation – scholarships, apprenticeships, support for health centres, food banks and the like – we would cheer their commitment to improving the lot of disadvantaged Indigenous Australians from the rooftops.

Corporate Australia should move out from under the shadow of RA for another reason, too. The separatism at the core of RA, and the RAPs signed by companies and groups across Australia is out of step with the result of the October 14 referendum last year when an overwhelming majority of Australians voted for unity, not division. That’s another way it saying it is time to get rid of Reconciliation Australia and its ineffective and divisive RAP program.

After last year’s referendum there is a new willingness to look closely at Indigenous agendas that favour division over unity.