20-somethings to drive engine of our economy

A fast-growing cohort of 20-somethings, driven by young migrants and the ‘Costello babies’ of the mid-2000s, is set to drive the nation’s economic engine over the next decade.

A fast-growing cohort of 20-somethings, driven by young migrants and the “Costello babies” of the mid-2000s, is set to drive the nation’s economic engine over the next decade and help offset the financial burden of the ageing baby boomers, experts say.

New government data reveals the looming shift in Australia’s age breakdown, with the most populous age this year of 33 falling to 27 by 2033-34.

Treasury’s 2023 Population Statement also shows the Covid-led rush to the regions is officially over, with most of the influx of international migrants set to stay in capital cities over the next decade.

It projects that the nation’s fertility rate will continue to fall, reaching 1.62 births per woman by 2034.

And it confirms Melbourne will finally pip Sydney as the nation’s most populous city in 2031.

The report project the national population at 31 million by 2034, with annual growth slowing from 2.4 per cent this year to 1.2 per cent by then.

But population ageing, flagged by Jim Chalmers as one of his government’s key medium-term economic and fiscal challenges, continues, with the nation’s median age projected to climb from 38.5 years in 2022 to 39.8 years by 2034. It notes this increase is being tempered by migration as younger-than-average people come to the country.

The data shows there are 405,300 people aged 33 across Australia this year, the most for any age. By 2033 the most populous age will be 27, when it is projected there will be 446,100 people.

Leading demographer Peter McDonald said the change is due to a combination of migration policy and a push by the Coalition government, led by then treasurer Peter Costello in 2004, for families to have more babies to help support population growth and the economy.

“We had a significant increase in the birthrate in the mid-2000s, the Costello babies, as incentives (such as a one-off Baby Bonus payment) were offered, as he said, to have ‘one for e country’,” Professor McDonald said. “The other reason for a potentially younger cohort flowing through is that age profile of migrants makes the overall population younger.”

Professor McDonald said these younger, work-ready people were in a position to be paying at least some of the taxes needed to support the increasing numbers of those Australians entering their 70s, 80s and 90s.

Economist Chris Richardson said it was more than simply greater numbers of younger workers bolstering the future tax base, it was their earning capacity as well.

“These 20-somethings are better trained, they’re digital natives, their education is better, their skills are more modern,” Mr Richardson said. “So it’s not just their numbers. Their shoulders are broader in terms of what they can lift for the budget than the equivalent group from generations past.”

He said while older people were increasingly costly as they used ever more expensive health resources toward the end of their lives, this was offset in part by many working longer into older age than previously forecast.

The Treasurer said the population statement provided critical information for governments to set policy, and had informed his government’s recent migration strategy.

“Net overseas migration is expected to decline back to around pre-pandemic levels over the next couple of years,” Dr Chalmers said. “Over the medium term, population ageing continues to be a significant economic and fiscal challenge for Australia.”

The political debate over our population has intensified as net migration spiked this year in the aftermath of Covid, reaching 518,000 in the year to June, driven by an influx of foreign students.

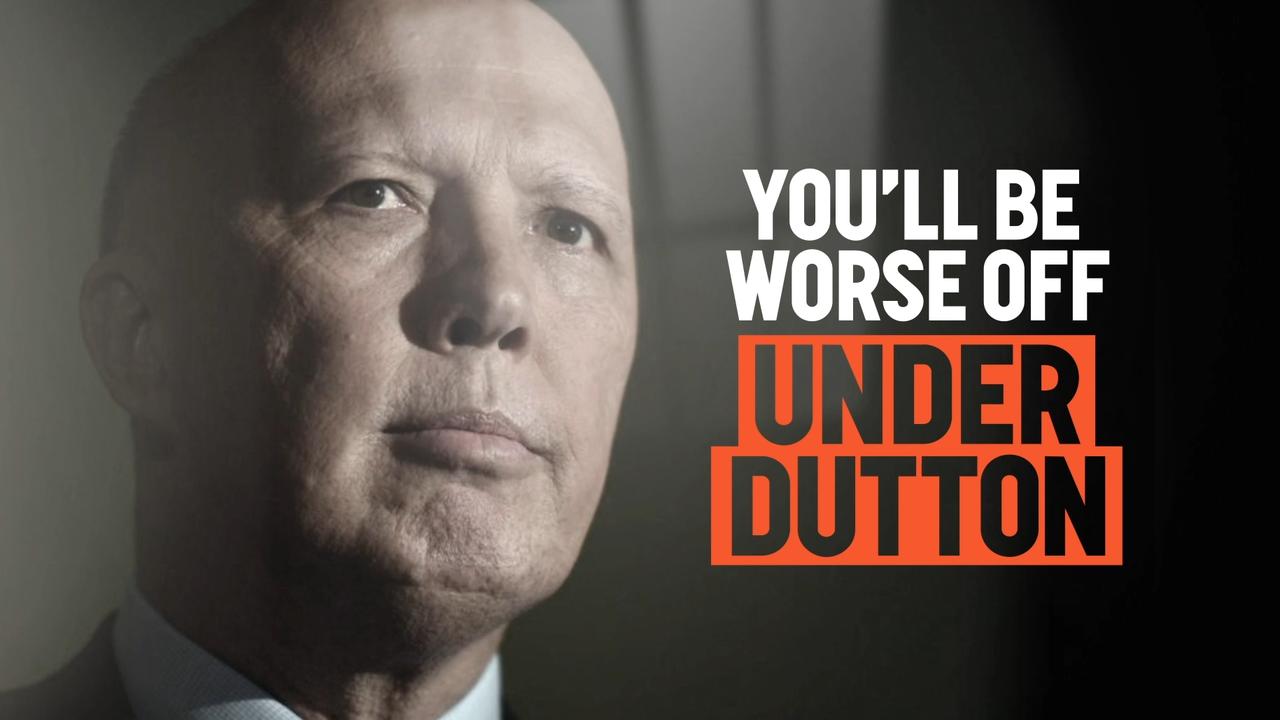

The opposition claims the Albanese government is adopting a “Big Australia” policy by stealth.

The statement confirms the end of the rush to the regions during the height of the pandemic in 2020-21. “With border closures and lockdowns, the combined capital city population shrunk by 0.3 per cent and fell behind rest-of-state growth (which grew by 1 per cent) for the first time since 1993-94,” it says.

“The reopening of borders saw (a) rebound in capital city growth. The population of the combined capital cities is projected to grow from 17.5 million in 2021-22 to 21.4 million 2033-34, an increase of 23 per cent. Over the same period, the population of the combined rest-of-state areas is projected to grow from 8.5 million to 9.5 million, an increase of 11 per cent.”

Professor McDonald said the clampdown outlined in the government’s migration strategy on qualifications needed for international students, including English language proficiency, would potentially lead to even greater concentrations of people in the capitals where the more prestigious universities were located.

Mr Richardson said while there was an economic benefit to greater numbers of high-skilled young people settling in our big capitals, there were costs as well.

“This group is wonderful for Australia, but it’s less clear that Australia is wonderful for them,” he said. “They will have better incomes, but with that comes higher expectations of what their society should look like, and in a range of areas – housing in particular, but also schools, roads, and broader infrastructure, we’re not keeping up … when it comes to spending on infrastructure to support that population growth it’s much less clear that we’re there. We’ve done it on the cheap.”

The report notes the other lever of population growth, fertility, continues to fall: “Australia’s total fertility rate is expected to gradually decline from 1.66 babies per woman in 2022-23 to 1.62 babies per woman by 2030-31, before stabilising. This reflects a long-running trend of Australian women having children later in life, and having fewer children.”

Professor McDonald said a fertility rate of 1.6, lower than the replacement rate, was “manageable given migration can supplement the shortfall by bringing in young workers”.