Or is it a broader question: how does migration sit within a population strategy that delivers the future housing and infrastructure required by all Australians and an economic platform that delivers wellbeing and quality of life?

The answer, of course, is that it is all of these things. Migration policy is highly complex, which partly explains the decades-long default to policy stasis. Getting migration right won’t solve all the thorny social and economic issues created by an ageing population, declining productivity and a volatile geostrategic landscape. But it can certainly help.

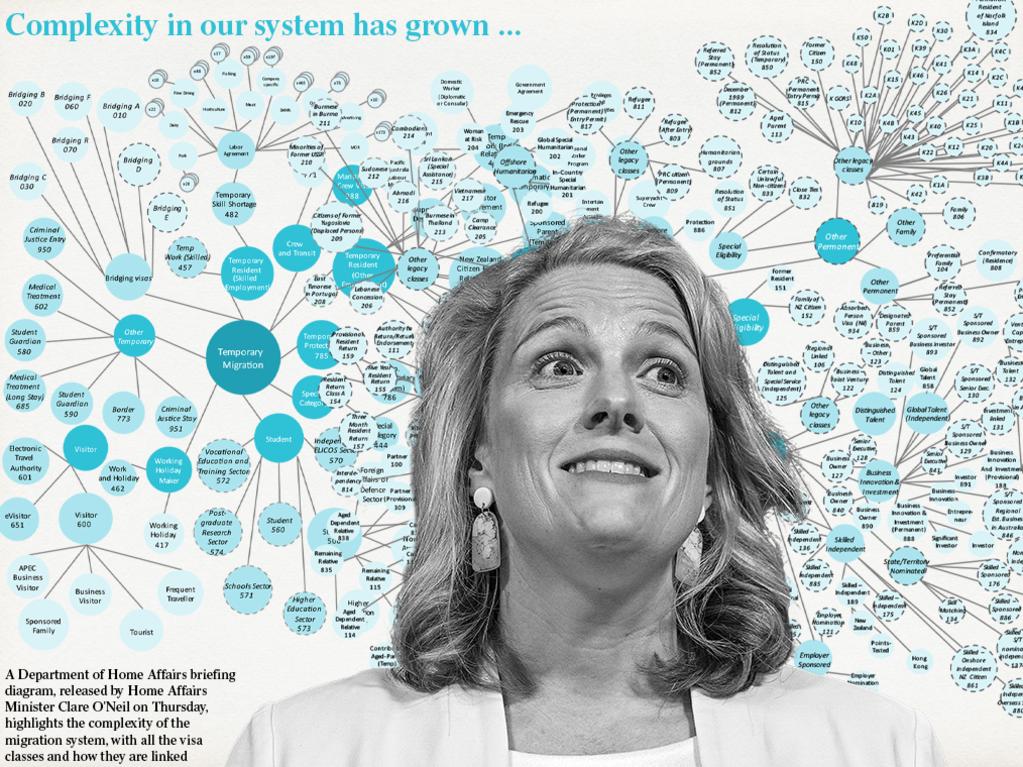

Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil has set herself a singular challenge in revamping the nation’s “broken” migration system, declaring herself ready to take on “the biggest transformation of our migration policy in a generation”.

“If ‘populate or perish’ described Australia’s challenge in the 1950s, ‘skill up or sink’ is the reality we face in the 2020s and beyond,” she told the National Press Club in Canberra on Thursday. “We aren’t bringing in the talent we need and we aren’t making the most of the talent we’ve got.”

That said, O’Neil plans to hasten slowly. She has released a draft outline of a new migration strategy, drawing heavily from a new review led by former Treasury secretary Martin Parkinson. The final strategy will be published later this year.

Parkinson’s report acknowledges the “success story” of migration in Australia’s history but excoriates the current system.

“The contribution of migrants has built the richly diverse, dynamic and multicultural Australia of today,” it notes. “It is no easy feat to incorporate people from all over the world into one country and for the end result to be socially cohesive and economically prosperous.” Then it puts the boot in: “Australia’s migration program is not fit for purpose. (It) fails to attract the most highly skilled migrants and fails to enable business to efficiently access workers. At the same time, there is clear evidence of systemic exploitation and the risk of an emerging permanently temporary underclass.”

Despite the pandemic and the resultant shutdown of migration offering a timely opportunity to reset, it simply didn’t happen. The Albanese government’s new strategy document acknowledges the policy drift. It notes a “back to front” system where temporary migration has overtaken permanent migration in terms of growth, resulting in fewer skilled migrants choosing Australia and the ones who do not being selected on the basis of their skills.

It acknowledges Australia’s complacency in seeing itself as a go-to destination for overseas workers. “As other countries make simpler, more appealing offers to skilled migrants, our migration system has become more complex so we risk losing our edge in the global race for talent,” it says.

It notes the Byzantine nature of the visa system. “Despite our shortage of workers in essential services, we ask an overseas trained nurse to pay up to $20,000 and wait up to 35 months to get their qualifications recognised and their visa granted.”

And it laments the lack of a multi-tiered approach to migration. “Despite (it) driving two-thirds of our population growth, we have not had a national long-term planning process that integrates migration with the state and territory government levers (such as infrastructure, housing and services) that make migration effective,” it warns.

Parkinson’s review says fixing temporary migration should be the government’s first priority. It sets an early and critical challenge, calling for “a tripartite approach, involving perspectives from industry, unions and government in determining the role of migration in meeting identified gaps in the labour market and delivering fair and efficient outcomes”.

O’Neil proposes a three-tier approach to fixing temporary migration. First, to fast-track high-skilled migrants for critical specialist roles in Australia. Second, to change the program for mainstream skilled temporary migrants to reflect modern Australia rather than the current jobs list, which hasn’t changed in a decade. And third is to be more transparent about low-wage migration, rather than allowing the international student visa system to act as a proxy for workers in low-paying industries such as the care economy.

As an early policy fix, from July the Albanese government will increase the income threshold for workers coming into Australia on a temporary skilled migration visa from $53,900 to $70,000. O’Neil said the old figure hadn’t changed for a decade and was lower than 90 per cent of all full-time jobs across the country.

“(Currently) a growing share of people entering Australia on temporary skilled visas are being funnelled into low-wage jobs,” she said. The skilled worker program “had morphed into a guest worker program”, she said, making participants vulnerable to exploitation. A higher salary threshold would mean higher-skilled applicants.

The government will also offer all current temporary skilled visa holders the opportunity to apply for permanent residency by the end of this year.

This didn’t mean the government was ready to open up the nation to any new version of a “Big Australia”. If all recommendations of the Parkinson review were implemented, a slightly smaller immigration intake would result across the medium term.

“I’m not someone who advocates for a Big Australia in this conversation,” O’Neil said.

There is much else for O’Neil and the government to do to right the migration ship, including tightening the rules around what constitutes an international student and putting an end to what the minister described as “permanent temporariness” in the visa status for hundreds of thousands of skilled migrants.

But the strategy, in whatever shape it eventually becomes, will be run out over years, not months.

O’Neil referenced Gough Whitlam in her speech, noting his burial of the White Australia policy and welcoming migrants into Australia from around the world.

She might have continued the analogy about the future of migration policy: “It’s Time”.

What is Australia’s biggest migration challenge? Attracting the world’s best and brightest minds in the face of increasingly stiff international competition? Modernising migrants’ skill sets to match the fast-evolving digital world? Ending the exploitation of low-paid foreign workers?