Parks Victoria is using hidden spy cameras in remote areas to detect and nab off-grid recreation users

Spy cameras hidden in trees and the bush are being used by Parks Victoria to try to prosecute off-grid rock climbers and walkers under its sweeping cultural heritage access bans.

You can now listen to The Australian's articles. Give us your feedback.

Spy cameras hidden in trees and the bush are being used by Parks Victoria to try to prosecute off-grid rock climbers and walkers under its sweeping cultural heritage access bans.

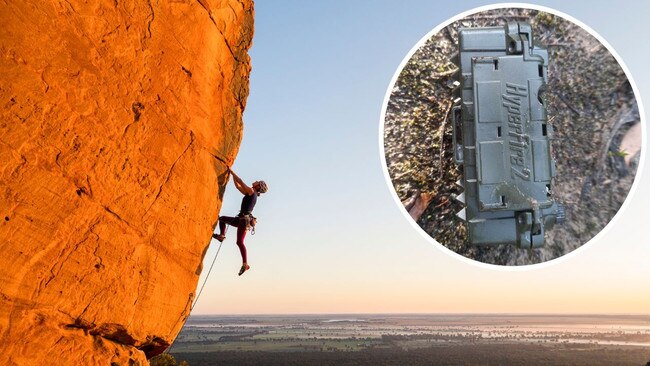

A remotely accessible camera has been found in a tree in Victoria’s Grampians National Park in the vicinity of once world-famous climbing locations.

The camera, when opened up, showed pictures of a Parks Victoria ranger walking with another camera and lens that climbers believe was to be used to photograph one of their community.

Despite the operation, Parks Victoria won’t say how many climbers it has fined for breaches of so-called special protection areas, which were introduced across vast areas of wilderness.

It is possible that only one climber has been detected in breach of the new laws that can include massive fines if harm is inflicted on rock art or quarrying sites.

Climbers have consistently said that cultural heritage should be protected but have questioned the failure to fully assess areas that have been included in the shutdowns.

Parks Victoria also has started introducing electronic counters in wooden posts to monitor areas to determine how many people are using the different trails.

One of the criticisms of the years’ old crackdown on climbing is that Parks Victoria used inaccurate information on climbing numbers to justify their bans.

Australian Climbing Association Victoria secretary Mike Tomkins said Parks Victoria rangers were monitoring people’s car registrations and camera footage was apparently taken of a restricted area.

The camera was in the Muline area, which includes some of Australia’s best climbing.

“It’s a truly world-class climbing area and that’s where the camera was,’’ he said.

Mr Tomkins said Parks Victoria would need evidence that someone had entered the restricted area and climbed.

“They would have to have photographs of the person climbing,’’ he said.

“There is footage of a ranger walking in with a long lens. It’s misuse of the national parks and now they are doing surveillance.”

Under the state’s Aboriginal Heritage Act, tangible and intangible cultural heritage is protected, with potentially big fines for anyone interfering with heritage, even if it is invisible.

Responding to the tough heritage laws, Parks Victoria shut down large areas of the Grampians from access.

This affected climbers, walkers and campers, allegedly to protect cultural heritage such as rock art.

Much of the rock art is invisible to the naked eye but experts, including climbers, have agreed that there is significant art worth protecting.

Yet the policy has been incredibly divisive, with little to no transparency over the content of the cultural heritage assessments.

A Parks Victoria spokeswoman said cameras and trail counters helped inform policy.

“Track counters help rangers count visitor numbers and make informed decisions about resourcing, trail maintenance and conservation, and cameras help prevent illegal activities like rubbish dumping or firewood theft,” she said.

Parks Victoria said it recently installed additional track counters at busy access points to count visitor numbers so that rangers could make informed decisions about resourcing, trail maintenance and conservation.

It said Parks Victoria staff regularly patrolled across the Grampians for issues such as illegal rubbish dumping or firewood theft.

Parks Victoria’s camera operations were run according to strict procedures and cameras were installed by authorised officers only at specific locations where alleged offences have been reported.

All cameras were installed within the requirements of the Surveillance Devices Act 1999 and all information captured by cameras was handled according to the law.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout