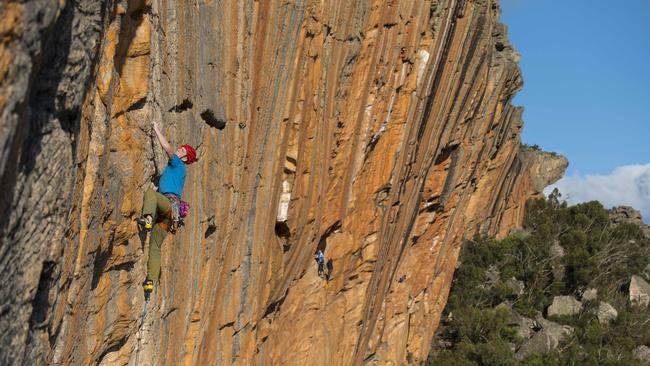

Scaling the face of sheer futility in the Grampians

Rock climbing has continued in the world famous Grampians National Park despite bans in some areas to protect cultural heritage.

Nearly four years after Parks Victoria shut down some of the world’s best rock climbing areas, climbers can’t find a single person having been fined and prosecuted for damaging cultural heritage or ignoring the bans.

Parks Victoria has conceded the Australian rock climbing community targeted over arguably the world’s biggest bans has been compliant since the bans were introduced in February 2019, but is refusing to say whether anyone has actually been punished financially or through the courts for any offences.

The rock climbing community says it is unable to find anyone who has been penalised or prosecuted, despite a long-running campaign by the government, which including highly contested claims about damage to cultural heritage.

Asked if anyone had been prosecuted over the crackdown, Australian Climbing Association Victoria president Mike Tomkins said: “No. And I don’t think anyone will ever be fined for rock climbing.”

Parks Victoria confirmed there had been a high level of compliance among the climbing community but would not say if any climbing fines had been imposed.

“Parks Victoria staff regularly patrol across Gariwerd (the Grampians) for a wide range of matters, such as illegal rubbish dumping or firewood theft. Where necessary we issue infringement notices under the National Parks Act,” a spokesman said.

“Specifically on climbing matters, we will always try to take an education-first approach as we know climbers want to do the right thing when and where they climb.

“While we don’t release operational details on the number of infringement notices issued, we’ve seen a high level of compliance and respect for the changes to climbing access since they were introduced.”

Barengi Gadjin elder Ron Marks, an experienced teacher of local Indigenous history, said it was important that informed people were trained well to explain the uniqueness of the country.

He said only a tiny minority of “dills” had ever done the wrong thing: “I maintain, if they look after the land the land looks after itself.”

For the first time since the government crackdown at arguably Australia’s two most important, globally recognised climbing locations – Gariwerd and nearby Mt Arapiles in western Victoria – the industry is starting to see how its pursuit will be managed in future years.

Parks Victoria has reopened to climbing half of the world-famous Taipan Wall in the northern Grampians but shut down access to some of the best routes, including those that attracted US free solo legend Alex Honnold to travel to Australia in 2014.

In a carefully managed process with the traditional owner groups, half of the distinctive red wall called Taipan was reopened a week ago, with the other half shut down because of Indigenous quarrying remnants, which are ubiquitous in the area. There is no rock art at Taipan, Parks Victoria said.

Mr Tomkins said the closed routes were the pinnacle of climbing in Australia.

“It would be the van Goghs and the Picassos of our culture,” he said.

The part opening of Taipan is being viewed as a mixed blessing for the climbing sector, which is staring at a new world of official permits and threats of massive fines if climbers do not comply.

If the same formula is adopted at Arapiles, up to 2000 routes could be lost.

What has infuriated Mr Tomkins and many of his friends is, he says, the fact that climbers wanted to be a part of the solution without being subjected to multi-year bans and the spectre of threatened livelihoods.

“Nothing in the world has ever been on this scale (bans),’’ he said.

Under the latest deal with traditional owners, Parks Victoria has agreed to conduct surveys of 50 more climbing locations in the Grampians by May, and by the end of next year introduce a permit system.

That permit system will effectively bind climbers to adhering to the government’s wishes, although there is another looming backlash over the intention to cut climbing at Arapiles – also known as Dyurrite – where a large stone-tool quarrying and manufacturing site was found.

The production site, which extends for around 200 metres around the base of a rock face, is where the Jadawadjali, part of the Wotjobaluk nations, manufactured a variety of tools from stone sourced all over Dyurrite.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout