Can rock art and recreation coexist in the Grampians?

It was one of the world’s best rock climbing areas – until Parks Victoria intervened, citing cultural heritage. What’s going on in the Grampians?

For decades some of the biggest names in world rock climbing have driven past the Giant Koala at Dadswells Bridge and turned left off the Western Highway towards the Grampians National Park. The park’s sawtooth ridges rise sharply above the volcanic plains to the south, and to the north dominate the Victorian Wimmera and Mallee in what is the last stop for the 3500km Great Dividing Range.

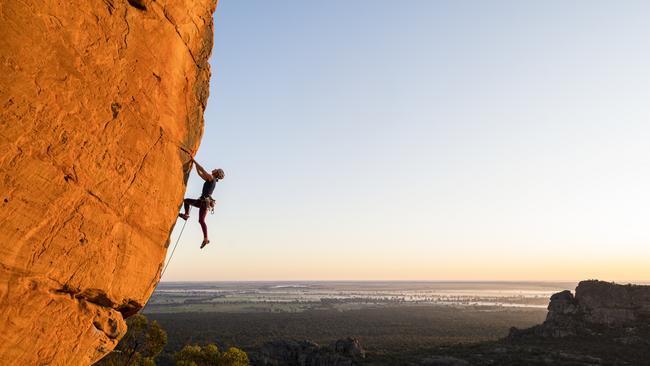

The Grampians’ sweeping sandstone walls, crags and overhangs, offering thousands of different routes from easy to extremely hard, have long attracted climbers. “It’s especially photogenic with the orange rock and the special Australian light,” says Tim Macartney-Snape, who summited Everest with Greg Mortimer in 1984, the first Australians to do so. “If you asked rock climbers around the world they would say, yep, the Grampians is up there with the best.”

Alex Honnold, the US climber who boldly ascended Yosemite’s El Capitan without ropes in 2017, has travelled to the Grampians and nearby Mt Arapiles, which he says has some of the best free soloing (climbing without ropes) in the world: “Everyone says it’s the best rock on Earth.” In 2015 he climbed Taipan Wall in the park’s Mt Stapylton Amphitheatre. At just 200m wide and up to 60m high, the sandstone cliff that glows orange in the evening light is widely considered by climbers to be Australia’s best single crag. Honnold, whose feats were captured in the Academy Award-winning documentary Free Solo, was lucky he climbed it when he did. It is one of many areas in the Grampians to have been permanently or temporarily closed to climbers under a controversial bid by Parks Victoria to protect Aboriginal art, sites of archaeological significance and the bush.

Just over a year after climbing was banned at Uluru, and soon after Rio Tinto blew up the Juukan Gorge rock shelters in the Pilbara against the wishes of traditional owners, the Grampians, or Gariwerd, and the neighbouring rock climbing holy grail of Mt Arapiles, or Dyurrite, remain at the centre of a bitter and protracted stoush over cultural heritage and recreational access.

Some 20,000 climbers a year flock to western Victoria, fuelling a multi-million-dollar tourism industry; yet the region also contains almost 90 per cent of south-eastern Australia’s rock art. Few dispute that this cultural heritage should be protected, but after well over 100 years of neglect of the indigenous footprint in the Grampians, one group has been singled out as the villain in one of Australia’s great environmental battles. Climbers say Parks Victoria has found its fall guys.

Jon Muir, 59, has a K2-sized adventure CV that includes solo summiting Everest, epic paddling adventures and the first unassisted transcontinental crossing on foot from Port Augusta to Burketown – 2500km over 128 days. He lives on an off-grid property that is shadowed by the beauty of the Grampians ranges. An expert climber, Muir says the Grampians and Arapiles are the product of a near-perfect conjunction of circumstances – walk-up access, a climate that affords climbing all year, and that magic rock. Like so many in the outdoors fraternity, Muir respects the traditional owners and their right to protect heritage sites but cautions against shutting out people from parks. “There’s room for everybody there. It’s not either/or; it doesn’t have to be. The climbers haven’t really been taken into the equation.”

The Grampians National Park is a sensitive site and its most visited areas are at risk of being loved to death. Its charm, beauty and proximity to Melbourne, three hours’ drive away, has made it a honey pot for tourists and walkers – about a million people visit each year. The environmental impacts are plain to see. The Pinnacle lookout walk, one of the busiest short hikes in Australia, is showing sad signs of neglect; at Silent Street, a narrow, rocky gateway to the walk’s climax, hundreds of people have scratched their names into the rocks. Elsewhere, visitors wander off tracks, trample over sacred quarrying sites or drop litter ranging from soiled nappies to beer bottles. At a rock shelter at Beehive Falls, faint rock art that could be thousands of years old is barely discernible because vandals have been hard at work, scratching their names on the roof and walls. Bullets and shotgun pellets pepper some sites.

Climbers leave their mark too, creating unofficial trails through the bush, using climbing chalk to improve their grip on the rock and fixing thousands of safety bolts on cliffs. Parks Victoria has produced dozens of photos of chalk trails and bolts and damaged vegetation but much of this purported evidence is hotly disputed by climbers, escalating the tensions between Parks Victoria, climbers and traditional owners.

Simon Carter, a veteran climbing photographer, has written the guide books on climbing at the Grampians and Arapiles. He sums up the depth of feeling in the climbing fraternity. “I believe climbers have been scapegoated to distract from far more serious impacts that are occurring to the cultural and environmental values of the park, appalling mismanagement and a sneaky move towards the commercialisation and commodification of our national parks,” he says. “Rock climbers have been wrongly vilified by parks staff or consultants in what I can only describe as a smear campaign based on absolute falsehoods.” He says that in the history of climbing in the Grampians, “we can’t find a single incidence where climbers have damaged visible rock art”.

The park can be divided into roughly three parts: the heavily developed and frequented Halls Gap area; the boutique southern end in Dunkeld; and the drier north, where climbing and bouldering occurs over hundreds of square kilometres of relatively isolated territory. While the equally famous Mt Arapiles, which lies outside the park, is often densely populated with climbers, the Grampians National Park is not. You need to hunt for climbers on most days if you want to watch them on the sandstone routes, lizard-like with slow but deliberate movements, ropes slapping and metal climbing aids tinkling as they rise above the bush.

Angst over climbing impact in the park has escalated in recent years despite the fact that Parks Victoria has long encouraged the pursuit, in part because climbers were seen as environmentally aware citizens who had helped manage the outlying areas of the Grampians and alerted the authorities to cultural heritage sites. But as traditional owners have gained a greater role in the management of the park, they have exercised their legal rights to curb certain activities on their land, drawing on heavy penalties written in Victorian law for damaging or failing to protect heritage.

There is broad agreement among climbers that cultural heritage must be protected but equally broad bewilderment about the way the Victorian government struck against their pursuit with virtually no warning. “Parks Victoria has been behaving like religious fanatics,” Carter says. “They have not listened or consulted, clearly they have not understood the activity, and they have relied upon absolute proven falsehoods as some sort of justification.” Macartney-Snape adds: “It’s really the way it has been managed. It’s a blight on Australian administration of natural land.”

The stoush came to a head this month when Parks Victoria announced that 66 climbing areas, covering up to 2300 of the best routes in the park, would be closed permanently and climbers would face a new permit system if they wanted to use the park at all. A further 126 climbing areas are being examined to determine whether the sport will face further limitations. While climbing may be allowed in 86 other areas of the park, it’s estimated that 80 per cent of the routes will be axed, effectively killing the destination as a global attraction.

Of the 125 climbing areas inspected during cultural heritage assessments, Parks Victoria says that 26 had Aboriginal cultural values. In 10 places it says there were one or more forms of harm reported, nearly half of which related to erosion and vegetation removal, plus the use of bolts and climbing chalk. A key challenge for every party affected by this dispute is that in many cases the rock art has faded to such a degree that it is difficult to see without specialist equipment. “Very little of it is visible to the naked eye,” Muir says. And cultural heritage can be both tangible and intangible under state law: it encompasses rock art, songlines and burial sites. Climbers say a lack of information about where sites are located has made it difficult to make accurate judgments about where to climb. Only now is Parks Victoria attempting to properly record and catalogue these sites and some will probably remain secret, depending on the wishes of traditional owners.

Many climbers are open to overhauling some climbing practices to protect indigenous sites but say attempts to set up avenues for constructive dialogue with traditional owners have been stymied by Parks Victoria. The Grampians Access Working Group, which gathered a petition with 31,000 signatures, says it believes issues can be managed with co-operation and education: “We believe that genuine collaboration between climbers and land managers will allow any restrictions on climbing to be finely and intelligently targeted, without resorting to the blunt instrument of the blanket bans that will drastically impact climbers’ access and also have immediate and profound effects on local tourism.”

When explorer Thomas Mitchell carved his way through the Grampians bush into the highest points of the area in 1836, his party could no doubt see the smoke rising from camp fires in Victoria’s west as the local Aboriginal people, already sadly depleted, struggled for space and life in their new world of guns, disease and poison. Mitchell had lost the foot race to the Grampians by 22,000 years but his presence guaranteed the 167,000ha that make up today’s park would never be the same, even if its deeply Australian beauty would be retained in the park’s most isolated areas.

The three traditional owner corporations, the Gunditj Mirring, Eastern Maar and Barengi Gadjin, explained in the foreword to the new Grampians management plan the pain of dispossession. “Our family units were ripped apart. Whole societies were deconstructed and many of us were met with a level of violence and coercion never before witnessed in our territories… We are rights holders for Gariwerd and our culture and heritage are central to its future management. Our spiritual and cultural connection to plant and animal species, rock formations, night skies and the wider setting of the mountain ranges are expressed in the largest concentration of rock art in Victoria.” Jake Goodes, a Parks Victoria employee and brother of football great Adam Goodes, has described seeing damage to cultural heritage as “really heart-wrenching”.

Eastern Maar Aboriginal Corporation chairman Jason Mifsud, a former AFL footballer who is now an emerging national indigenous leader, says the way the state legislation has been framed has the capacity to pit interest groups against traditional owners. “We’re only playing by the rules as traditional owners under the [cultural heritage] act,” he says. “Unfortunately the rules haven’t been either well understood or well policed by Parks Victoria.” While understanding the plight of rock climbers and the emotion of being banned from many areas, he urges all parties to focus on the issue of protecting heritage. “We have empathy that some of those routes have been closed to ensure that cultural heritage assessment and protection is upheld,” Mifsud says. “I think they need to focus on the problem and not the people.”

Uncle Ron Marks, a Wotjobaluk elder with a long history in the Grampians and Mt Arapiles, told The Weekend Australian soon after the bans were imposed that common ground could be reached between indigenous leaders and climbers. Most climbers, he said, knew how to behave. “But then there are the dills that don’t give a rat’s clacker. And that’s like everywhere,” he said.

Cultural heritage damage in the Gariwerd is an old story. Warnings of damage have gone unheeded since the late 1800s, when shearers and farmhands would gather at Billimina shelter on the park’s western edge, poking sticks at art, drawing over it and kicking aside the remnants of stone quarrying that is prolific in the region. Historians and archaeologists have reported for generations on the need to protect the Grampians rock art but nothing meaningful, other than some iron cages and occasional signs, was ever done.

In 1982, several Victorian archaeologists tolled the bell on government inaction, declaring in a joint report: “As we have noted, the paintings in all of the shelters are extremely faint and pale and are gradually vanishing.” A Victorian Archaeological Survey report warned that an “ultimate salvage” operation was needed across the park to protect the art; it would be nearly four decades before the government of the day hit the panic button.

Professor Ian Clark, a Victorian Aboriginal heritage expert, warned in 2001 that governments had failed to properly manage 10 key indigenous sites, citing a 1990 meeting where there had been confusion about management issues. “The condition of the public art sites had degenerated to such a state that they were an embarrassment,” he said.

For most of the past two years there has been a creeping sense that Parks Victoria has finally woken to the impact of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006, which carries fines of up to $1.6m for failing to prevent damage to indigenous sites. In 2017, a Victorian farmer near Melbourne was fined $20,000 for knowingly harming Aboriginal heritage by extracting sand from his quarry where indigenous artefacts were found.

In many ways, the Grampians and Arapiles are emerging as the Victorian test case for cultural heritage protection amid a clearer understanding of traditional owner connections across the state, from the banks of the Yarra River to the Great Ocean Road and the High Country. Some wonder whether this western Victorian battleground is the start of something bigger.

The argument over the future management of the park is not whether these heritage sites should be protected, but how they should be protected and who should wear the blame for damage. Grampians-based archaeologist Ben Gunn warned in the early 1980s of the threat of damage to sites. “Even the most fastidious management controls cannot remove the threat of the vandal and no conservation can fully replace a damaged or destroyed site,” he wrote.

Gunn has since identified what he claims to be climber damage of cultural heritage areas. He co-authored with the Parks Victoria ranger Jake Goodes and others a paper this year that acknowledges that much of the graffiti in the Greater Gariwerd is not produced by rock climbers. But it also claims that in some sites, “it is all too apparent that climbers are at fault”. Powdered climbing chalk is included in his overall definition of graffiti.

Australian Climbing Association Victoria president Mike Tomkins says there is no evidence that climbers have left graffiti on sacred sites and rejected claims that bona fide climbers have caused vandalism. And herein lies the problem – Parks Victoria says one thing, the climbing community says another. Adding to the outrage are false or unverifiable claims made against climbers. A key photograph released by the department showed rock art punctured by a bolt, claimed to be the work of climbers; in fact it was part of an old safety cage used by government land managers to protect the rock art, and an apology was issued. “It was just terrible,” Tomkins says of the images, which went around the world as evidence of climbers’ wrongdoing. “So much baseless rubbish.”

Climbers say Parks Victoria has mistaken bird droppings and naturally occurring rock stains for chalk. Environment minister Lily D’Ambrosio was sent a series of photographs from Parks Victoria last year purporting to show evidence of climbing damage, but in many cases it was unclear who had committed the harm, and another departmental briefing greatly exaggerated environmental damage in eight parts of the national park. Parks Victoria later admitted this error as well, scaling back damage from 7.425ha of the park to 0.7ha.

Meanwhile, Parks Victoria has been clearing a new boutique bushwalking track the full length of the park, stripping out large areas of pristine bush as they cut their way to Dunkeld.

Parks Victoria chief executive Matthew Jackson could not have imagined the blowback from the local and global climbing communities. But he insists there is significant evidence of inappropriate bolting, chalking or rock breaks. “Rock climbing in the Grampians will continue, we’ve always said that,” Jackson promises. But with good news comes bad. “I can’t lie. There’s going to be some challenging discussions.”

He concedes that Parks Victoria and its predecessor entities have been slow to respond to the issue of protecting cultural heritage. “We probably should have implemented this as an organisation earlier,” he says. “And I’ve made that clear to the community and the stakeholder reference groups. However, when damage or potential damage is brought to our attention at any time… we need to act. We have legislated responsibilities. I’m comfortable that we had enough evidence to show there was damage to either environmental or cultural assets … that we had to immediately stop. We are bound by legislation to do that.”

There will be unavoidable, long-term effects of the bans that may take generations to wash through, particularly in places such as Natimuk, population 514, the gateway to Mt Arapiles. Some wonder if the new cultural heritage bans announced for Mt Arapiles will kill the town, its pub and climbing shop that rely heavily on the recreational trade at the mountain.

Publican Bill Lovel says the impact of reduced climbing at Arapiles will be broad, affecting customers such as the New Zealand Army and special operations police who have trained there, bringing in thousands of dollars to the town during each visit. Parks Victoria has conducted several briefing sessions for residents but Lovel is, like many, deeply unimpressed. “There is no accountability, that’s how I would read it,” he laments. “The town’s people would like to know what’s going on. It’s what I would call the old ‘divide and conquer’ strategy.”

Climbing, perhaps more than any other pursuit, takes fortitude and breeds a connection with the bush and the rocks. It explains the passion in the debate over access.

Jon Muir is back climbing at Mt Arapiles and reckons there is nothing quite like being part of the place’s community, which is part-hippie, part-climbing, part-camping. “It’s a very rich culture at the mount and it’s a climbing culture that’s invaluable there,” he says. “To wake up to the sounds of nature with the big cliffs looming over, particularly with the first rays of the morning sun – that orange rock just glows. You can’t really put a dollar value on the quality of that outdoor experience to an individual.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout