Not one Indigenous voice to parliament but many: Noel Pearson says local communities must be heard

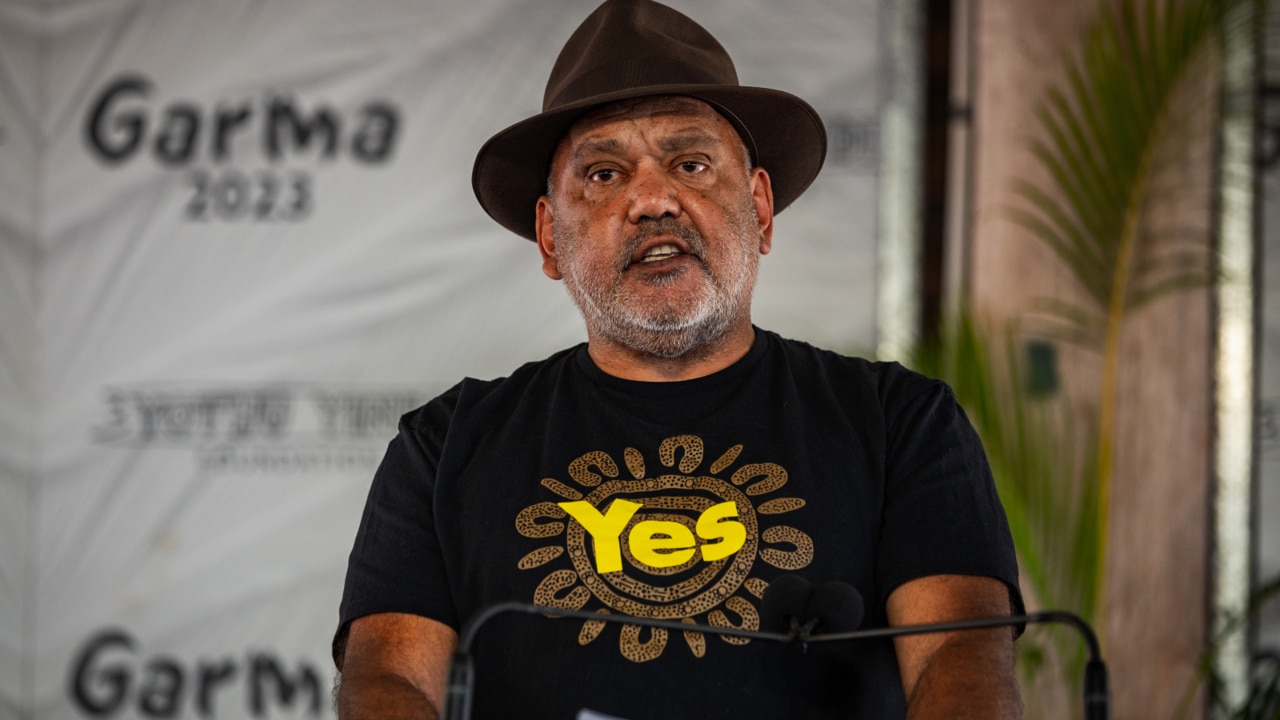

Noel Pearson has urged the Albanese government to commit to establishing local voices in remote Indigenous communities, describing the proposal as a ‘game-changer’.

Noel Pearson has urged the Albanese government to commit to establishing local voices in remote Indigenous communities, describing the proposal as a “game-changer” to turn around the fortunes of the Yes campaign.

On the eve of early voting in the Cape York coastal community of Aurukun, where Mr Pearson’s land rights advocacy began as a 25-year-old lawyer for Wik elders in the late 1980s, the voice co-architect said the Calma-Langton model of local Indigenous voices needed to be embraced. When asked what Labor could do to turn around the referendum campaign – with Newspoll showing support for Yes at a new low of 36 per cent – he said local voices were the key to igniting support for a voice in the final three weeks.

“The work on the Calma-Langton committee does need to be picked up; local and regional voices, that’s essential for the joint parliamentary committee (that’s been announced),” he said.

“The voice is irrelevant in a place like Aurukun if it is not local. That’s the game-changer, a true local voice in remote communities, to advocate for floodlights on the football oval, new housing for 30 to 40 families without a home, a new strategy for hygiene. It’s going to be the voice in the CWA (Country Women’s Association) halls, and by the river banks, and in the shire hall – and, in Aurukun’s case, under these mango trees,” the Cape York leader said.

“A four-sided table with local government, state government, the federal government, and the community.”

As a young lawyer, Mr Pearson co-founded the Cape York Land Council, using funds chipped in by Wik elders who had been saving their pensions to advance the fight for land rights.

“My Wik friends … I first came here when our mayor’s mother (mayor Keri Tamwoy’s mother Alison Woolla) was the mayor,” he said. “I was 25 years old. Now, I’m an old man … I can tell you what they wanted for you and your children. They wanted the Wik people to live forever, to grow up their children with their language, their culture, to be healthy and educated. They had a dream for your people and your culture.”

Mr Pearson said 30 years after the Wik case – a landmark High Court decision that ruled native title rights could coexist with pastoral leases – the struggle for recognition continued. “The local voice is the most important, the Wik voice. We want the Wik voice to operate here, under these mango trees, when it’s not raining, and you’ll sit down and do business with the government,” he said.

Indigenous academics Marcia Langton and Tom Calma recommended 35 regional and local groups to be established first to link to a national voice. The local voice groups would be spread across the country and advise all three levels of government.

As the latest Newspoll revealed support for a Yes vote continuing to fall, Mr Pearson said he was terrified that Indigenous people’s reconciliation attempt would be rejected. “I’m terrified that our people have reached out, and that’s so vulnerable, and the last thing we want is for that to be repudiated,” he said.

“But there’s no path (for the Yes campaign) other than optimism and positivity and the message (that the voice) will bring the country together.”

On Tuesday morning, the Australian Electoral Commission’s remote voting team will fly into Aurukun and set up a makeshift polling place for two days; locals will also be able to vote on October 14.

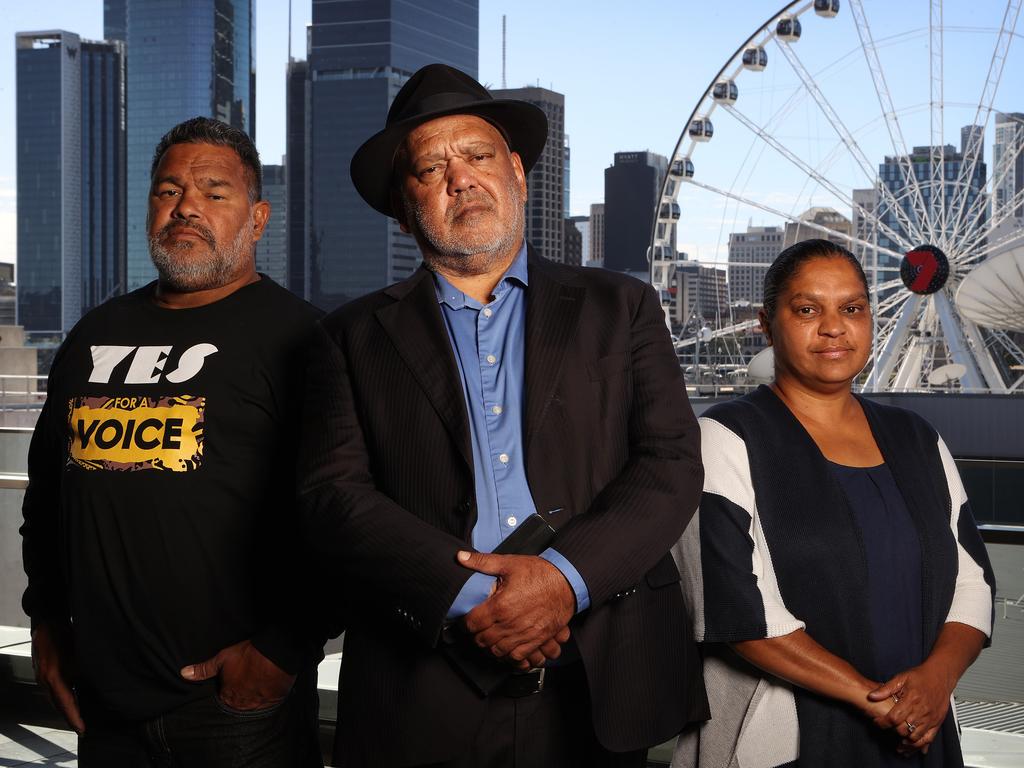

Aurukun mayor Keri Tamwoy, a traditional owner of the Putch clan of the Wik nation, said a local voice was crucial to lifting her people out of poverty and unemployment, and to deliver cost-effective and useful government programs.

The township is home to about 1100 people, where the median age is 27. It is plagued by 80 per cent unemployment and disproportionate rates of rheumatic heart disease and diabetes, and school attendance sits at just over 30 per cent.

“There’s anywhere between 110 and 115 (state and federal) government-funded programs in Aurukun, and they would cost many millions,” Ms Tamwoy said. “But when these programs are born, there’s no input coming from a grassroots level. We don’t have a say. They’re born in airconditioned offices in sky-rise buildings down south. They do not consult or acknowledge Indigenous people. That’s why there’s a whole heap of money being poured into our community with no results. There’s no clear fix but we must be consulted on policies for us.”

Former mayor Dereck Walpo, now a local commissioner for the welfare-managing Families Responsibilities Commission, told the town meeting that he backed a voice for Aurukun if the community was represented by a local.

“I strongly believe it’s got to be someone from this community, from the five clans, that has to sit on the panel, (to talk about) education, employment and housing,” Mr Walpo said.

Apalech elder Phyllis Yunkaporta, who at 61 lives in a house with four other adults and six children under 10, said she would be among the first in line to vote Yes on Tuesday.

“When I was born, I was not (properly recognised as) an Australian citizen,” said Ms Yunkaporta, who was six when the 1967 referendum to officially count Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders as part of the population was successful.

“We of course want to be recognised, especially in the Australian Constitution – we have to be made part of that.

“Wik people have always been fighters for rights, and I stand on the shoulders of those giants. I just want to make things better for the next generation, for our Aboriginal community and others in remote areas.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout