Indigenous voice: Watered-down version of New Zealand experience a step in right direction

Australia’s Indigenous voice will have only a fraction of the abilities afforded to New Zealand’s Maori but could be an important step towards a broader treaty, an expert says.

Australia’s Indigenous voice will have only a fraction of the abilities afforded to New Zealand’s Maori but could be an important step towards a broader treaty, an expert on Maori public policy says.

The Indigenous voice outlined by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese on Thursday will be able to make representations to parliament and executive government on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, although it will not deliver any services or have any veto powers.

In contrast, the Maori people have had representation in NZ since 1866 and there are seven Maori seats in the NZ parliament. The country also has a Waitangi Tribunal, a powerful court-like body that considers claims brought by Maori alleging breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi signed between the Crown and the Maori back in 1840. Dominic O’Sullivan, an adjunct professor at Auckland University of Technology and a professor of political science at Charles Sturt University, said the key difference was that New Zealand’s model was a voice in parliament, rather than Australia’s proposed voice to parliament.

The dedicated Maori seats meant there was always likely to be a Maori presence in both government and opposition.

“Maori perspectives are always the centre of parliamentary democracy and parliamentary decision making. Maori don’t always get what they want in terms of policy outcomes, but there’s never any doubt as to what those aspirations and expectations might be,” he said.

He said the extra authority was why there were “significantly greater” opportunities for Maori self-determination compared to Australia’s First Nations people.

Australia’s voice, however, could help pave the way for further measures.

“The Prime Minister’s right to say it’s a modest proposal but it can still be influential and it can be built upon in time. It’s the first step in a process of treaties and truth telling, and I think one of the useful things that the voice will be able to do is contribute to debates about what treaties should look like, what they should achieve, and why they might be important both symbolically and practically,” he said.

“I don’t think we can expect a revolution in Indigenous policy immediately, but I think we can expect perhaps incremental changes on a permanent basis.”

Critics of the voice have argued that the new body will set Australia on a path towards a NZ model.

The Institute of Public Affairs, which has joined with right-wing activist group Advance to lead the No vote push, argues that the NZ system has stoked growing racial divisions in the country.

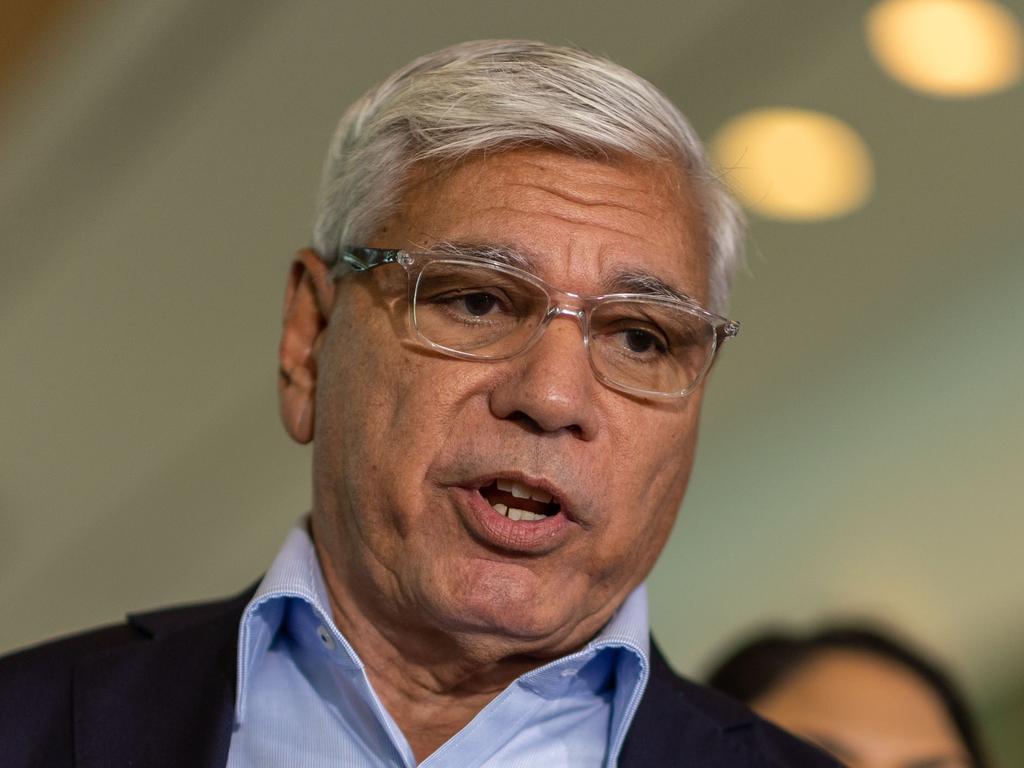

The IPA’s John Story said the Waitangi Tribunal had crept from being an advisory body to an effectively binding and entrenched part of the political system.

“NZ is a lot further down this path than Australia and it hasn’t been a very successful path,” Mr Story said.

“If you talk in terms of reconciliation, NZ is probably more divided on issues of race than it’s ever been. It’s a toxic issue that permeates throughout NZ politics.”

He noted that Mr Albanese had previously cited NZ as the path Australia should follow on Indigenous reconciliation.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout