Breakdown shows some NT schools each receive up to $9m less than their allocated budget

An analysis of Northern Territory schools most affected by underfunding shows all but three had an Indigenous student population of more than 95pc and were remote.

The Northern Territory government’s “broken” education funding model has left some schools with budgets more than $9m short of what they were to receive.

In 2021, some schools received only 30 per cent of their allocated income; 34 of the 151 government schools received less than half of their allocated income on My School.

All but three of these schools had an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island student population of more than 95 per cent.

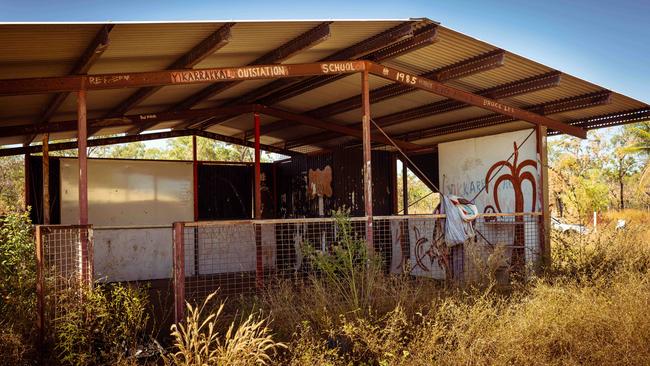

Many of the most-affected schools were remote.

NT: Schools in crisis

The shocking state of NT education

If the students at Gamardi are lucky, a teacher will turn up two days a week. For whole months, nobody comes. And then there is the sorry excuse for a classroom. ‘If this was happening in an urban setting, they’d sack the government on the spot.’

Kids fall off the money-go-round

While lush lawns and gardens welcome students inside Alyangula, less than 20km away, Angurugu’s imposing gates present a bleak, very different picture.

Schools short-changed by millions

An analysis of Northern Territory schools most affected by underfunding shows all but three had an Indigenous student population of more than 95pc and were remote.

Security, prospects take toll at schools

Attendance rates at remote Northern Territory schools are as low as 18.7 per cent and have been falling for a decade.

Scandal of the nation’s forgotten schoolkids

The NT school system is failing students by leaving at least one in five effectively unfunded, offering an education so bad that most fail minimum literacy and numeracy standards.

Urban schools were also underfunded, and larger schools had the highest funding gap in dollar terms. In three large Territory schools (Palmerston College and Taminmin College, on the outskirts of Darwin, and Katherine High School, 300km south of the capital), the gap between allocated budget and reported income was more than $9m each, according to figures on national school funding transparency website My School.

Several former teachers and former department staff have told The Australian that underfunding was responsible for the Territory having the country’s poorest academic results and lowest literacy levels.

In the 2023 NAPLAN results, more than half of all Northern Territory students failed every test category, except year 5 reading, which had a failure rate of 49.9 per cent.

Under the new NAPLAN system, students are assessed against four levels of proficiency: “exceeding”, “strong”, “developing” and “needs additional support”.

More than 80 per cent of the Territory’s Indigenous students failed every category, except year 7 writing (79.4 per cent failure) and year 9 spelling (77.9 per cent failure).

The majority (68 per cent) of the NT’s Indigenous students were in the lowest band, “needs additional support”, across age cohorts, compared with the national rate of 33 per cent.

“There’s a level of dysfunction in the schools that’s so hard to untangle,” one former teacher, who cannot be named, said.

“The funding system is broken. We were chronically under-resourced; as teachers, there was no way we could be successful.”

A Department of Education spokesperson said the school budget “represents the portion of overall school resourcing that is directly managed by the school” but schools do receive other income. They said the My School figure included other centrally managed funding, either through direct school expenditure (including principal remuneration, housing, some leave and relocation costs) or corporate and school service costs.

However, the department was unable to provide school-specific breakdowns of costs and services attached to centrally managed funding and to the bureaucratic spending. It also confirmed that attendance-based funding models accounted for how school budgets were allocated.

Since 2015, the NT has been the only jurisdiction in Australia to fund on the basis of attendance rather than enrolment.

Late last year, after the release of a damning review into NT school funding, the government committed to moving to a new model within five years.

NT Education Minister Eva Lawler said it was especially important to recognise the needs of Aboriginal and remote students to improve results.

“As Minister for Education, it is my absolute focus to support every child right across the Territory so they become valuable contributors and future leaders of our community,” she said.

“I have been working closely with our federal Minister for Education, Jason Clare, lobbying for full funding for each and every Territory school.

“This is important work, and work which is making progress. I thank the federal Education Minister for the $40.4m he has already invested into central Australian schools to see them reach full funding”.

The NT Department of Education did not answer queries about whether the funding levels reported on My School represented the reduced funding, after the attendance-based model had been applied, or whether they represented what funding would be if schools were fully funded to the level of their enrolments.

Mr Clare last week confirmed that NT students were the most underfunded in the country, and received only 80 per cent of their “full and fair funding level”.

He said the next National School Reform Agreement was all about fixing the funding gap and the resulting education gap.

Australian Education Union Northern Territory president Michelle Ayres said the 20 per cent funding gap meant one in five students was effectively unfunded and the remote, Indigenous and disadvantaged children, who were “bearing the brunt of underfunding”, couldn’t afford to wait for a new funding model.

“[Attendance-based funding] is breaking our schools. Our schools are at crisis point,” she said.

Teachers and former teachers, who cannot be named because NT government contracts prevent them from speaking to the media, said underfunding meant that schools were cutting teachers, replacing experienced teachers with recent graduates and axing essential programs, including literacy programs.

They said the biggest impact of underfunding was the learning challenges in their students.

“You feel the lack of resources most in the classroom, because of how far below the expected standards the students are,” one former teacher told The Australian. “You can’t bridge the gap. It’s a scale and a depth issue – there are too many students with really high needs.”

Kylie Stevenson, Caroline Graham and Tilda Colling are independent journalists working in the Northern Territory and Queensland. This project was supported by the Meta Public Interest Journalism Fund

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout