Groote Eylandt’s starkly different two schools show NT’s education funding inequality

While lush lawns and gardens welcome students inside Alyangula, less than 20km away, Angurugu’s imposing gates present a bleak, very different picture.

Remote Groote Eylandt’s Angurugu School was allocated more than $3.2m in 2021. But by the time the money went through the Northern Territory government’s school funding model, its actual budget was less than a third of that: $969,075.

What happened to the other $2.2m – 70.3 per cent of the school’s allocated income – is complex. But even a stroll past the school is enough to see something has gone wrong here.

Angurugu is a small Aboriginal community, in the Gulf of Carpentaria, 630km from Darwin. Its school grounds are bleak. A rusting playground sits empty on long-dead grass, behind an imposing fence. Even though there are about 100 school-aged children living in the community, when the final bell rings only a handful of students trickle through the gates.

“You should see the difference in the facilities at Alyangula,” one community member says.

Alyangula is the neighbouring community, also on Groote. It’s a service town for the manganese mine on the island and a range of government workers, mostly from the mainland. Alyangula is less than 20km from Angurugu, but community members say the difference between the two schools illustrates something about educational inequality in the Northern Territory.

NT: Schools in crisis

The shocking state of NT education

If the students at Gamardi are lucky, a teacher will turn up two days a week. For whole months, nobody comes. And then there is the sorry excuse for a classroom. ‘If this was happening in an urban setting, they’d sack the government on the spot.’

Kids fall off the money-go-round

While lush lawns and gardens welcome students inside Alyangula, less than 20km away, Angurugu’s imposing gates present a bleak, very different picture.

Schools short-changed by millions

An analysis of Northern Territory schools most affected by underfunding shows all but three had an Indigenous student population of more than 95pc and were remote.

Security, prospects take toll at schools

Attendance rates at remote Northern Territory schools are as low as 18.7 per cent and have been falling for a decade.

Scandal of the nation’s forgotten schoolkids

The NT school system is failing students by leaving at least one in five effectively unfunded, offering an education so bad that most fail minimum literacy and numeracy standards.

In Alyangula, where less than 5 per cent of the resident population is Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, the school is not hidden behind a fence. It has lush lawns and gardens, with a row of inspirational pencil sculptures to welcome students inside. Alyangula Area School isn’t overfunded – in 2021, it received only 52 per cent of the allocated income reported on My School in its school budget –$2.6m of its students’ funding was not distributed directly to the school.

Every school in the Northern Territory is underfunded, according to national standards. It’s just that the underfunding is distributed unevenly.

Experts, educators and communities all over the Northern Territory have come forward with urgent concerns about the gaps between Indigenous and non-Indigenous education, as well as urban and remote education. Groote Eylandt’s schools are not an anomaly. What is unusual, on Groote, is that the two educational realities are so close together.

Angurugu might be the most extreme case of underfunding in the NT, but exclusive data analysis by The Australian reveals that across the Territory there is a gulf between what is allocated to schools, reported via the national My School website, and the budget schools receive from the NT Government.

In 2021, the other school on Groote Eylandt, Alyarrmandumanja Umbakumba School (also located in an Indigenous community) had an actual budget of 30.5 per cent of its allocated income, a $1.42m shortfall. In Arnhem Land, Elcho Island’s Shepherdson College had a shortfall of $8.41m (it received 37.2 per cent of its allocated income), while Laynhapuy Homelands School’s budget was $2.96m short and just 39 per cent of its allocated income.

On a percentage of income, the most underfunded schools were concentrated in remote and Indigenous communities. Of 151 government schools in the Territory, 34 received less than half the income reported on My School in 2021 in their actual budgets. All but three of these schools had an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Island student population of more than 95 per cent, and most were remote.

“I think it’s a fair assumption to make that there’s a problem there with the funding model,” says Batchelor Institute of Indigenous Tertiary Education professor John Guenther.

The Northern Territory is the only jurisdiction in Australia – and one of a handful of places in the world – to fund schools on the basis of attendance, rather than enrolment. The Australian’s year-long investigation, NT Schools in Crisis, will explore the complexities of attendance tomorrow, but broadly, NT attendance rates are in decline. In term two this year, average rates were 74.3 per cent but in very remote schools, attendance rates are less than half , and in some schools below 20 per cent.

The NT government has committed to moving to a new, enrolment-based funding model within the next five years.

Northern Territory Education Minister Eva Lawler, an educator for 40 years, said she understood the “value and importance of engaging and improving outcomes for Aboriginal and our most remote students”.

“Intensive work is currently under way to build stronger foundations for long-term improvement for Aboriginal students in the NT,” she said. “We also continue to prioritise building, recruiting and retaining an expert workforce right across the board. This will ensure students in the Northern Territory receive the highest-quality education.”

The Territory government has not provided a timeline for the rollout of its controversial funding model, beyond promising it would be within two to five years.

Former Territory Labor politician Scott McConnell, who grew up in Central Australia attending remote schools, says there is no reason the government couldn’t implement a fairer funding system immediately.

“With the bail law reform, they wrote them in the morning and passed them in parliament that afternoon,” he says. “It’s systemic racism – a view that Aboriginal people don’t need an education.”

Guenther was also concerned that under the budget released in May, students were “stuck with” the same model for at least another year. “(It’s) a model that we know is inequitable and arguably racist, because it does target Aboriginal kids, whether intentionally or not.”

While remote schools were underfunded at a higher rate, the financial impact – in dollar terms – was concentrated in large schools. Katherine High had a budget almost $10m short of its $17.98m allocated income; Palmerston and Taminmin colleges in Darwin had more than $9m shortfalls.

“My School is a fiction,” says one teacher, who can’t be named.

The Australian has discovered that in 2021 there was a $269m gap between school allocated income and actual school budgets. In 2020, the gap was $264m.

A school’s budget is not the full resourcing for the school; a Department of Education spokesperson said schools also received centrally managed direct school expenditure (including principal remuneration, housing, some leave and relocation costs), as well as centralised or “corporate” and school service costs.

A small part of the gap is accounted for by income schools receive in parent fees and donations, which totalled $22.7m in 2021 and $16.6m in 2020, and was concentrated in higher socio-economic areas. However, there are two main factors that explain the gap between school income and budgets: the portion the Territory government takes for its centralised bureaucracy and services shared across schools; and the Territory’s controversial attendance-based funding model, which has been described as “systemic racism”.

Australian Education Union Northern Territory president Michelle Ayres says principals often approached her with concerns about the gap between the money they receive and what’s reported in My School.

“The whole point of My School is transparency,” she said. “It’s a website that should be aimed at parents. You shouldn’t need to be a statistician or an economist to understand how much is being spent educating your child.”

The attendance-based funding model is a huge part of what complicates school funding in the Northern Territory, because it means many enrolled students are not funded. Ayres brushes off the obvious question: Where does the money saved through attendance-based funding go?

“Well, it doesn’t exist,” she said. “That’s part of the problem.”

Ayres started her career as a graduate teacher working on the Arlparra homelands, 280km north of Alice Springs. The job was as rewarding as it was heartbreaking, because of “the inequity”, she says.

When people talk about school funding, Ayres always thinks of one particular student: a primary school-aged girl with trauma and behaviour issues. The student couldn’t read a single letter, and Ayres said she would shut down when a task became challenging.

“I’ve had this moment with a few kids. It’s like they’ve been told all their life – whether it’s them telling themselves or the system telling them – but you can see that they don’t think they can do it. They have been given this belief that, ‘This is just me, I can’t write, I’m never gonna do that’.”

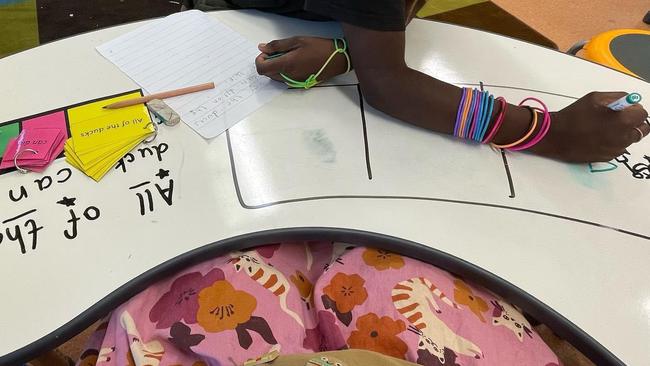

But Ayres says the school managed to get the girl to attend daily and be excited about learning. It took years, but eventually the girl wrote a story. It was a huge breakthrough. Ayres snapped a photo of the moment.

Years later, she was showing someone the picture and realised how underfunded the school had been. The table, chair and carpet were paid for out of a grant. In another part of the classroom, out of frame, several local assistant teachers were teaching the girl’s classmates. Their wages were being paid by an external grant, which was taken away from the school the next year.

In this moment of educational achievement, Ayres says, the school’s budget paid for almost nothing – even the pencil, paper and eraser likely came out of back-to-school vouchers.

Ayres says teachers all over the Territory make compromises without the resources to support their students. “It’s always a constant decision: What am I trading off to achieve that with her?”

At a glance, it might seem like Northern Territory students are generously funded. Nationally, students are funded using a School Resourcing Standard to estimate how much money each needs.

SRS begins with a base rate, then applies needs-based loadings for students with disabilities, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students, socio-educational disadvantage, low English proficiency, school size and remoteness.

Both federal and Territory governments make contributions to SRS, which go into a funding pool, but Ayres says it’s important to understand the SRS is the minimum waterline.

“The SRS is not an aspirational funding standard,” is how education economist Adam Rorris puts it in a 2020 report. “It is not a desirable level of funding that would give schools an ideal pool of resources to discharge their teaching and learning obligations towards children … the SRS is an essential minimum level of funding for school systems.”

SRS is designed to provide enough money for four in five students to reach minimum literacy and numeracy standards. It doesn’t provide additional support for the one in five children who aren’t reaching the standard, or resource students to achieve benchmarks in other subjects such as science, history, sport or the arts.

Under SRS, Territory students receive substantial loadings. More than 70 per cent of NT schools are in remote or very remote regions, some inaccessible during the wet season. It also has a large concentration of small schools; 27 per cent had fewer than 50 enrolments in 2021. The jurisdiction has high levels of social disadvantage. Providing education here is costly.

When SRS was created, the sample did not include Territory public schools. There are concerns the standard doesn’t reflect the real costs of remote education. For example, one remote independent school told The Australian a trip to the nearest major town for basic supplies could cost $600 in fuel.

However, the AEUNT says this is not the urgent issue. Its most pressing concern is that the Northern Territory education funding pool, compared with the minimum waterline, is only about 80 per cent full, according to an independent report last year – an average shortfall of $6374 per student. Across 33,700 public school students, The Australian estimates the total shortfall is $214.8m a year. Effectively, it leaves one in five students unfunded

“The model that the government came up with is that people who are bearing the brunt of underfunding in the Northern Territory are our least advantaged people,” Ayres says. “That’s what we mean by a human rights violation. Every child in the world has a right to be educated, and our government has come up with a way to say, ‘No, we’re not funding these kids to be educated because we value them less’.”

“It’s systemic racism,” says Guenther. “That’s what it is. Whether you like to call it that or not, it’s discriminating against Aboriginal people in the bush, because they are living in the bush. And because they’re Aboriginal.”

Northern Territory and federal governments both make contributions to the funding pool. Under a bilateral agreement, federal contributions to education are about 20 per cent, while the NT government contribution sits at about 60 per cent. This leaves a substantial unfunded gap – 19.4 per cent.

Federal Education Minister Jason Clare said the National School Reform Agreement aims to address the “funding gap” and the education gap it has created. However, he acknowledged the NT has “the most underfunded schools in the country”.

“They receive approximately 80 per cent of their full and fair funding level and, under current funding arrangements, are not on track to achieve 100 per cent of the SRS before 2050,” he says.

“We also know that if you’re a child from a poor background or from the bush or an Indigenous Australian, you’re three times more likely to fall behind at school, and not a lot of those children catch up.

“Australia has a good education system, but it can be a lot better and a lot fairer. Not every school is fairly funded … in particular in the Northern Territory.”

Minister Lawler said she had been lobbying for additional federal funding to cover the shortfall.

“I have been working closely with (Clare), lobbying for full funding for each and every Territory school,” she said. “This is important work, and work which is making progress. I thank the Federal Education Minister for the $40.4m he has already invested into Central Australian schools to see them reach full funding.”

But in the meantime, the inadequate pool of resources is distributed using the NT government’s funding model, which, since 2015, has been based on attendance.

Ayres says a fundamental problem with attendance-based funding is that disengaged students, who might attend irregularly, actually require more time, attention and resources in the classroom.

At schools such as Angurugu, attendance is both the symptom and the cause of the funding problem. As attendance falls, Ayres says, schools lose funding and, as funding drops, schools lose the ability to re-engage students. They make cuts. School becomes less and less appealing, then attendance and funding drop again – a cycle of disadvantage, she says.

And in the meantime, schools receive no income for their most challenging students. The AEUNT estimates in 2021 there were 7000 students who generated no direct funding for the schools in which they were enrolled in.

Yolngu man Yingiya Mark Guyula, the independent member for Mulka, has been trying to track where the school funding earmarked for his Arnhem Land communities is going.

“It’s not being seen and people have wondered where it is,” he says. “I’ve always been asked, ‘We’ve been promised all this money, but where is it?’.”

Earlier this year, he obtained data, using a written question, that a large part of the funding never made it to the schools.

The Northern Territory government response said in 2022, Elcho Island’s Shepherdson College had 203 unfunded students (of 505 enrolments), while Maningrida College, in East Arnhem Land, had 187 unfunded students (of 407 enrolments). In Gunbalanya, more than half (121 of 229) students were unfunded. The schools did nor receive a cent of recurrent funding for unfunded students.

The impacts of attendance-based funding are perhaps worst in Homeland Learning Centres, remote “classrooms” attached to “hub schools” in a larger town. These are not separately funded, and funding and student outcomes are not reported in My School. The Yikarrakkal HLC is a tin shed and The Australian understands there are at least five HLCs in Arnhem Land like it.

“Our schools are doing the best they can,” Ayres says, but the reality of the underfunding is that almost every school is making compromises. She says one was choosing between high and low-literacy programs. The Australian has also been told schools are cutting engagement programs, reducing the number of teachers, or replacing experienced teachers with recent graduates to save money. It is understood one school in a remote area that has produced many well-known musicians has cut its music program.

Educators also say it’s not just the amount of funding that’s the issue, but how much it varies year to year. As attendance fluctuated, some school budgets dropped by more than 30 per cent between 2022 and 2023, which makes it difficult to offer teachers long-term contracts – a huge barrier to recruitment in remote areas – and limits the programs they can run.

Over a five-year period between 2019 and 2023, 71 schools experienced budget cuts. Laramba School, in the central desert, had its budget drop 36.8 per cent over that period, from $874,663 to $518,902. Of the 15 schools with the biggest budget cuts (more than 20 per cent drops), all except one had Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander student percentages of more than 98 per cent.

NT Anti-discrimination Commissioner Jeswynn Yogaratnam said the inequitable outcome as a result of the attendance-based funding model was “clear”.

“This goes against the fundamental rights of the child as safeguarded in the Convention on the Rights of Children,” he says. “Article 28 of the Convention is on the right of the child to education with a view of achieving this right progressively and on the basis of equal opportunity.” The present model failed to achieve equal opportunity; indeed it promoted inequitable outcomes.

“It is not reflective of the difference in the sociocultural determinants and challenges between a remote community school and an urban school.”

Kylie Stevenson and Caroline Graham are independent journalists working in the Northern Territory and Queensland. This project was supported by the Meta Public Interest Journalism Fund.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout