Aboriginal art from the APY Lands at centre of stunning whitewash claims

A four-month investigation uncovers stunning new claims — and footage — over the level of white involvement in bringing APY Lands’ prized art to gallery walls | Watch the video

The young white studio staffer kneels down in her splattered overalls holding a bucket of paint at the edge of a massive canvas. She’s in the compound of a remote artists’ studio 1400km from Adelaide in the tiny desert settlement of Amata.

“Could it do with another rockhole there, or is that going to be too circular?” she says to her boss, Rosie Palmer, the manager of the outback Tjala Arts centre.

It’s an odd question to direct to her white colleague because to their side stands one of Australia’s most revered Indigenous artists – and this is her art.

Yaritji Young has paintings hanging in the art galleries of NSW, Queensland and South Australia. Last year she flew to Thailand to see her pictures in the Bangkok Art Biennale. Her larger works sell for more than $60,000. A stunning painting she did with her siblings, the famous Ken Sisters, won the prestigious Wynne Prize in 2016. She’s had a career that most young arts graduates can only dream of since first picking up a paintbrush long before these two women were born.

This painting is supposed to be an interpretation of Young’s Tjukurpa, her ancient and sacred stories of customs and law. The studio assistants appear to examine the canvas then Palmer says: “Can I juice this one up a little bit?” This scene is depicted in a short video, captured on a phone and obtained by The Australian.

As Young calls out to someone in Pitjantjatjara to bring some cool soft drinks, Palmer dips her paintbrush into the bucket and with a confident swirl sloshes big, bold red circles on the canvas.

“That’s actually nice that space through there,” her offsider comments as Palmer dips into the bucket again and slicks another layer of red paint on to the Indigenous artwork.

When The Australian calls Palmer to question her about painting on Young’s canvas, she at first insists she doesn’t work directly with the artist.

Presented with a still photo from the video, she declares in an email she was holding a brush for Young while the artist put down her background washes: “I absolutely deny that I am painting in this photo,’’ she says.

White hands on black art: an investigation

‘She’d pick up a brush … she knows how white fellas view art’

A four-month investigation uncovers stunning new claims — and footage — over the level of white involvement in bringing APY Lands’ prized art to gallery walls | Watch the video

In the frame: APY art centre to face probe

The APY Arts Centre Collective faces investigation for possible criminal or civil charges after a six-month probe into the controversial organisation sparked by The Australian.

White hands, cash and ‘coercive control’

Indigenous artist Jennifer Inkatji had just started a new painting when she left Skye O’Meara’s studio for dialysis treatment. She returned to find it finished and up for sale | WATCH

APY art chief must step aside: integrity tsar

An investigation into the APY Art Centre Collective will ‘forever be under a cloud’ while manager Skye O’Meara remains, a public integrity advocate says.

Claims of white hands on black art: ‘Can I juice this one up a little bit?’

Serious claims and confronting video evidence about white involvement in the making of Indigenous art have been levelled at one of Australia’s most successful and prominent arts organisations.

Aboriginal art collectors should know exactly what they are getting

In an age when respect, integrity and authenticity are at the centre of community expectations, uncomfortable issues have been raised by serious allegations of what is happening in the studios of the APY Art Centre Collective in South Australia.

‘We won’t brush scandal under carpet’

The government minister driving an investigation into allegations of white interference in black artwork suspects some in the arts establishment ‘want us to brush it under the carpet’ but she has vowed to get to the truth.

Stretch to believe report has drawn a line under it

It is hard to feel that the NGA report has done much to allay the suspicions that hang over the APY Art Centre Collective paintings, let alone the management of the APYACC.

‘White hands’ centre given exhibition ban by Top End gallery

The Museum and Art Gallery of the Northern Territory’s director Adam Worrall will not work with the APY Art Centre Collective following its expulsion from the Indigenous Art Code.

APY group expelled from Indigenous Art Code

It comes after a months-long investigation by The Australian revealed claims by APYACC studio staff and artists that white staff painted substantial sections of Indigenous paintings.

‘White hands concerns are valid’

NT Arts Minister has written to Tony Burke to push the ‘valid and numerous’ concerns Indigenous art industry leaders have about a SA-led probe into the APY Art Centre Collective.

For the past four months, The Australian has been investigating serious allegations about white hands interfering in the making of black art in the studios of the wildly successful APY Arts Centre Collective (APYACC), of which Tjala Arts is a member.

We’ve been met with vehement denials, pages of emotional testimonials, repeated legal threats, a NSW Supreme Court injunction attempt, and one emphatic assurance: white staff never meddle in the artistic process during the creation of Indigenous art.

In a statement posted on the organisation’s Instagram account, the APYACC denied it had interfered with artists’ Tjukurpa, and said that some photos and videos were not put to the APYACC.

It also denied that Palmer was unduly interfering in famed Indigenous artist Yaritji Young’s painting in a video supplied to The Weekend Australian. As well as access to the Instagram post, a full report on the APYACC statement can be found at the end of this article.

Remote art haven

The APY Lands are high on the list of the world’s most remote and sparsely populated places.

Up in the top left corner of South Australia, 2000 Anangu live in tiny communities dotted across vast ancestral lands the size of Germany. The local electorate office is literally half a continent away, down on the coast at Port Augusta, further than the distance between Sydney and Brisbane.

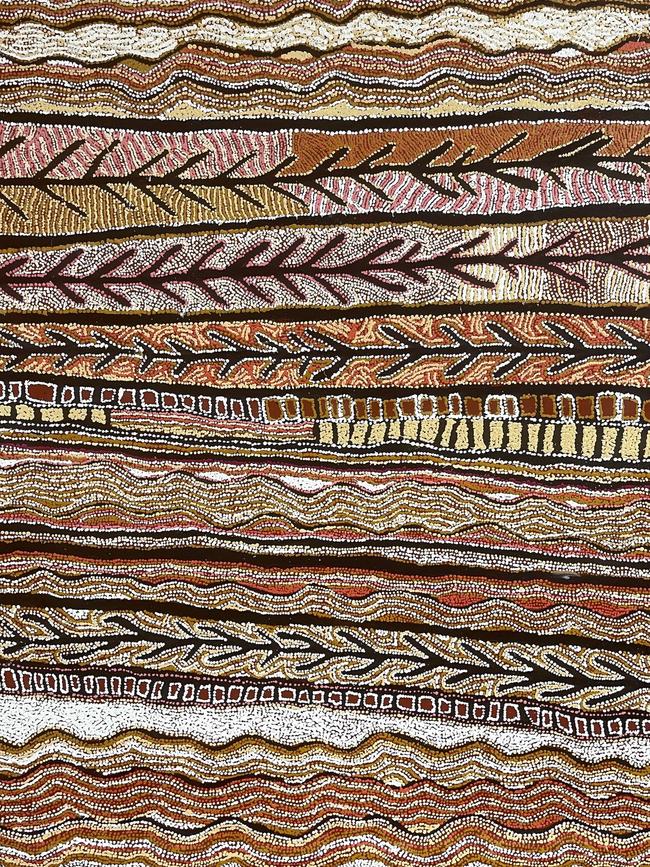

This extreme isolation has allowed the Anangu to hold tight to their traditions. English for the majority is a second or third language. It’s an impoverished and sometimes violent community, but knowledge of the old ways is strong. It’s this hand that reaches back into the time before that endows Anangu art with its vibrancy, and its value. The art movement that sprouted in the seven community arts centres on the lands is now in radiant bloom. In the past few years, its artists have taken home a LandCruiser-load of Australia’s most prestigious art prizes, including the Wynne and the Archibald. APY paintings hang in the Pompidou in Paris and the Guggenheim in Bilbao.

The National Gallery of Australia will soon host Ngura Pulka – Epic Country, “one of the largest and most significant First Nations art projects” ever assembled, featuring artists aligned with the collective.

In the often gossipy and competitive world of the arts, one thing is not in dispute: the person most responsible for the stunning success of this black arts movement is a white arts administrator, Skye O’Meara. In 2016, O’Meara, who had spent almost a decade as the manager of Tjala Arts, was the driving force behind the establishment of the APY Collective, which she set up with an “unashamed commercial focus” to market art from the APY Lands.

By any measure, it’s been an extraordinary success. Swank APYACC galleries have opened in Sydney and Melbourne, and it has just moved into new headquarters in Adelaide. Some of its top artists earn well north of $100,000 a year and support their impoverished extended families. In the 2021-22 financial year, the collective made sales of $3.8m, of which $3m was returned to artists and arts centres on the lands. It’s received millions of dollars in government and philanthropic funding.

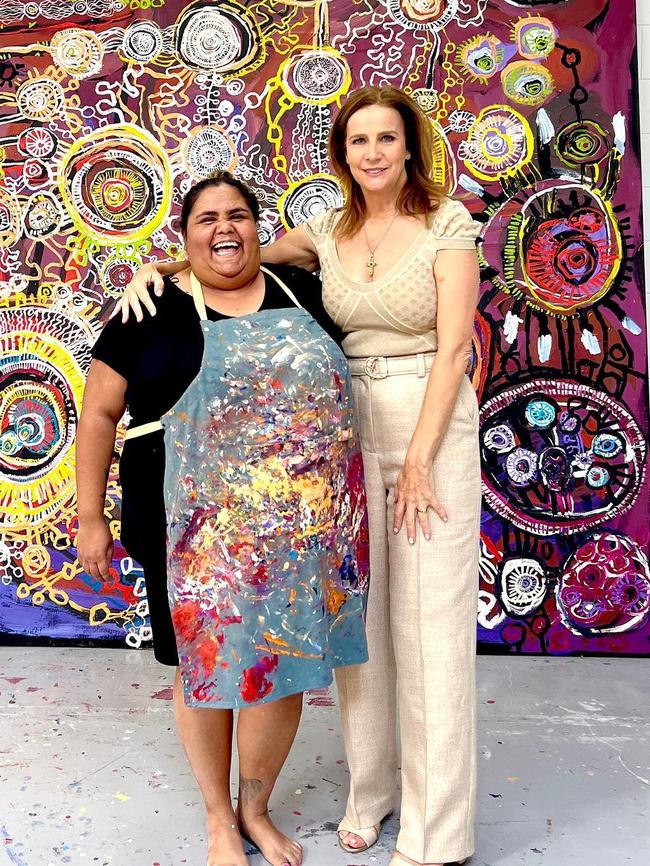

O’Meara can be charismatic, and is connected. Actors Russell Crowe and Rachel Griffiths have been photographed in the collective’s studios, and former South Australian premier Steven Marshall and acclaimed artist Ben Quilty are close friends and fierce defenders. Quilty describes art from the APY as “the greatest art movement on the planet in my lifetime”.

APYACC board member Sally Scales, an Anangu artist recently appointed to the NGA Council, says: “What we have achieved would not have been possible without the expertise, skills and relentless work of Skye O’Meara. Skye supports us to dream big. The collective is changing the world.”

But the achievements of O’Meara and the artists she has fostered have been met by some with scepticism and outright disapproval in the tiny, factional and intersecting worlds of art and Indigenous politics. She now finds herself at the centre of an ethical conundrum at the heart of the Indigenous art industry – what part should white people play in the making of Indigenous art?

Late last year, The Australian boarded a small plane with Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney for the long, bumpy flight out to the APY Lands. O’Meara was in the desert to greet Burney at the tiny settlement of Kaltjiti, dressed in paint-spattered pants and an “I (heart) APY” T-shirt. She was the master of proceedings, directing people and guiding Burney into a chair among the mob of black faces for a ceremony to welcome the minister on to country with song and dance.

It was through this trip that a number of people expressed concerns about the power O’Meara holds, and wields, over the APY arts scene and the practices that are alleged to occur in the collective’s Adelaide studio.

In a four-month investigation, The Weekend Australian has interviewed dozens of people involved in the sector, including Indigenous artists, former gallery staff and industry figures and we are left with two diametrically opposing possibilities: either O’Meara and her white studio staff have regularly interfered in the artistic process in the making of Indigenous art; or, as O’Meara and the board claim, she is the target of a cruel, complex conspiracy by jealous enemies, who have pressured artists into making false allegations to bring down O’Meara and to inflict financial pain on the collective.

Rival driving forces

APY art is revered by galleries and art lovers but it is also a commodity, haggled and squabbled over like any other.

For the artists, it is an expression of their Dreaming. “If you ask an (Indigenous) artist why they paint, money comes about fifth on the list,” an old industry figure tells me. “They’re looking at the dissolution of their culture and the wayward behaviour of their kids and grandkids. They believe that it’s through art they can pass on their stories.”

The tension between these two realities, the material and the spiritual, is at the heart of this story. Artist Paul Andy is keen to tell us his part of the story.

When he hears from relatives about our inquiries, Andy insists we talk also to him. On our first trip to Adelaide, in a videoed interview, he says last year he was working on a painting in the collective’s Adelaide studio, depicting his grandfather’s Tjukurpa – sacred law and stories.

“That story was emu dreaming,” he says. He claims O’Meara painted on it, changing his design. When asked why, he shrugs and says: “That must be her dreaming.” He claims O’Meara regularly painted on his paintings. “When there were other (artists) there, she would do the same for those other artists as well,” he says.

The Weekend Australian later receives a retraction letter from Andy, sent via APYACC lawyers, saying: “I was told to say a story about how Skye says ‘no, no, no’ when she doesn’t like the way an artist is painting. It’s not true … white people can’t touch Tjukurpa, it’s too strong … I didn’t mean it. I was wrong.”

In later telephone calls, Andy claims he was presented with a letter to sign by the collective and he thought it was about returning to work at the Adelaide studio.

On this trip, we also interview artist, actor and filmmaker Derik Lynch, who spent a couple of months in the Adelaide studio in the autumn of 2020. Lynch claims he saw white staff interfering in the Indigenous telling of sacred stories. “It made me very uncomfortable,” he says. “I did not like a white person picking up a brush and painting an Anangu painting. You don’t do that. It’s very disrespectful.”

Lynch claims the white staff and O’Meara were pushing artists to paint in a style palatable to a white audience. “She would pick up a brush and tell them how to do the dots,” he says. “(O’Meara) knows how white fellas view Anangu’s art … and so she shows them how to paint in terms of the contrast and how it is going to look on a wall in exhibitions.” If they were in a rush to get paintings finished for an exhibition, he claims, O’Meara would paint on one end of a canvas while the artist painted on the other.

On the day we interview Lynch, we also speak to another celebrated Anangu artist, who in taped, on-the-record interviews, gives vivid and detailed accounts of artworks having been allegedly interfered with in the Adelaide studio. However, when we later send O’Meara questions outlining this artist’s claims, the artist recants.

“I admit that I have spoken to … Greg Bearup about some issues with Skye and the collective,” she says in an email. “Today I have decided the collective is my home, and I wish to withdraw my claims … I realised I was on the wrong path, saying the wrong things to the wrong people.”

It is not the only letter of recant. The artist Rhoda Tjitayi is one of a number of artists who send letters through the APYACC’s lawyers. She says the work produced in the APYACC’s studios is “100 per cent made by Anangu”.

“The work is ours and the Tjukurpa is ours … and anyone who says this is (not the case) is lying,” Tjitayi says. “I have been tricked and pushed into sharing my story with (the) journalist Mr Greg Bearup, which is causing me so much pressure and stress. I have been pushed into telling a lie about what happens in our art centre by people who are jealous of APY Collective.”

The Weekend Australian never interviewed Tjitayi. We did, however, interview another artist over the phone, who regularly paints in the Adelaide studio. She claims O’Meara and other white gallery staff painted substantial sections of many of her paintings, and many other artists’ paintings. “I would do 70 per cent and they would do 30 per cent,” she says.

It makes her feel “ashamed”, she says, to have the white artists interfering in her work. “I know that other (artists) are watching and it’s like, ‘She never really done that, they were helping her’ … That’s not my painting! I can’t even put my Tjukurpa on there!”

This artist claims frail and elderly painters are presented with massive canvases and would have difficulty completing the work without “Skye and the workers helping them out … they’re old and they’re lazy and some of ’em have got half a body in the grave”.

She describes the relationship between the artists and O’Meara as like being in a bad marriage. “You’re just trying to keep ’em happy,” she says. “You just shut up and do the job.”

This artist originally spoke on the record and was photographed, but after O’Meara received our questions, the artist requested we not reveal her identity. She claims she received a phone call from a gallery staffer telling her that this writer was a “bad man”.

One of the artists tells us they have a collective nickname for the studio staffers (there are often four) – they call them “The Forty Finger Artists”.

The Weekend Australian is not suggesting these claims are true, only that they have been made. It considers it in the public interest to publish the allegations and the APYACC’s denials, explanations and responses so a proper discussion can be had about what is appropriate and ethical in the production of Indigenous art.

Romlie Mokak – the sole Indigenous commissioner on the Productivity Commission and the author of its recent report into the sector – says the allegations made by these artists are “serious claims” and it is an important issue to investigate.

Mokak says the expression of things that are cultural and sacred is essential to the maintenance of Indigenous culture. “Anything that pretends to be Tjukurpa that is not is problematic,” he says.

O’Meara has long been a vocal and forceful advocate for ethical practices. In an article she co-authored in The Guardian in 2019, she wrote: “Many are saying this is a conversation that needs to be had … The Indigenous art market has always been fraught with scandal … (the artist) Mike Williams states in his work: ‘Don’t touch what is not yours’.”

In her article, O’Meara explained the deep significance of Tjukurpa to the Anangu: “The term ‘Dreaming’ is too frivolous, too small to capture the meaning or magnitude of Tjukurpa. It is better described by Anangu of all ages as culture, land, lore and story, but also Anangu identity, reason for being and explanation of the world.”

The staffers’ accounts

While the artists interviewed give vivid descriptions alleging what happened to their paintings in the Adelaide studio, it is the accounts of five studio staff that help explain why.

They claim O’Meara had a “rigid aesthetic” and felt she knew what white buyers wanted in black art, and so pushed her artists, and staff, to adhere to that aesthetic.

“The directive to studio staff is to make a piece as marketable and as profitable as possible,” one former staffer says.

She claims she and other staff were directed to get paintings “over the line”, and up to a standard deemed good enough for an expensive sale or an exhibition. This woman admits she herself painted significant sections on Indigenous paintings in the Adelaide studio and was instructed to do so. She declined to be named, as did the other staffers, fearing for her career in the arts sector.

However, this former employee signed a statutory declaration outlining her allegations and is one of a number of people who say they would be prepared to give evidence in court under oath. She worked at the studio for a significant period.

“If there is a portion that Skye doesn’t think fits, she will just paint over the top of it when the artist isn’t there,” she says. “The artist will come back the next day and go, ‘What happened to this bit?’”

The main clientele for the big-ticket artworks, this former staffer says, are galleries such as the NGA and wealthy patrons.

“They like a European style of composition and so that’s what Skye tries to adjust people’s paintings for,” she claims.

This former staffer says there are different tiers of artists and she alleges it is on the big works with the big artists where the most work is done by white gallery staff.

“Anything that is (for sale) above $5000 would have a white hand in it,” she claims.

The board claims no artworks are interfered with.

Having worked in the studio, the former staffer claims she can now look at paintings from the Adelaide studio “and I know exactly where it has been interfered with or where Skye’s hands have been”.

Whenever someone unexpectedly came into the studio, she claims, someone would sing out “hands off” and gallery staff working on a painting would fade away, leaving the artists alone. She says when then premier Marshall came in unannounced, this “hands-off” call would go out.

Another of the former studio assistants says she saw O’Meara painting on the works of Indigenous artists “at every stage” of the process and that this happened regularly. She claims that when O’Meara was painting on their canvases, the artists would “look up at you and they would raise their eyebrows, or they would kind of grimace – sometimes they would be too ashamed to acknowledge what was happening”.

A third staffer says when O’Meara painted on their canvases, the artists would say, “Oh, that’s Skye’s Tjukurpa.”

O’Meara, the board, and numerous other artists who have worked in the APYACC’s studio vehemently deny all the allegations. “There’s no intervention,” Scales says.

The board says the only time a staffer would touch a painting is to prepare a canvas, or to paint over spills, or if a dog walks on a canvas – they black it out at the request of an artist.

When asked in an email is she ever picks up a paintbrush and paints on Anangu artwork, O’Meara says: “My staff and I have a deep and ongoing respect for Tjukurpa” and any claims she painted on Indigenous canvases are false and highly insulting to the artists.

The Australian spoke to more than a dozen art professionals, gallery owners and administrators working in the Indigenous arts sector. The overwhelming consensus is there should be zero intervention in the artistic process.

One gallery owner, who sells Indigenous art, says the paintings would be impossible to sell if buyers knew there had been a white hand in them. O’Meara and the APYACC agree, and say the only assistance is purely functional and at an artist’s direction.

Concerns grow

There have been whispers in the art world about the practices in the APYACC’s studios for a number of years.

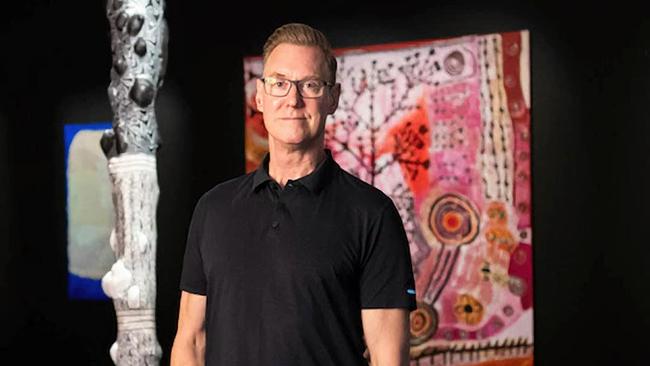

Gallery owner and art buyer Adam Knight says it was about 2020 that he started to become concerned about what he was hearing and seeing.

Knight has been one of the biggest Australian supporters of the APYACC, having bought more than 50 paintings worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

He buys Indigenous paintings for wealthy clients and, over many years, amassed the impressive collection now housed at Bond University for businessman Patrick Corrigan. It is Australia’s largest private collection of Indigenous art on display.

He’s now stopped buying the works of certain artists when they paint in the APYACC’s studios, he claims, “where I believe there has been manipulation” by white staff.

Knight has stopped buying Young’s artwork when she paints in the APYACC’s studios. He tells The Weekend Australian this before the Tjala video is filmed. He claims his suspicions were heightened by the stories of artists who work between the APYACC’s studios and other studios.

When artists have been working in studios, outside the APYACC’s network, he has sent requests for them to produce paintings of a similar style to ones they had produced at the APYACC’s studios. “They (the artists) say they can’t do the same work because most of their (paintings done in the APYACC’s studios) are done by white people,” Knight claims.

The Weekend Australian is not suggesting Young has acted inappropriately in any way.

Former Sydney gallery owner Adrian Newstead says that over the past few years, he has been “troubled” by works coming out of the collective’s Adelaide studio.

Newstead has been in the trade for more than 40 years and was the managing director of art auction house Deutscher Menzies. “No one has seen and appraised more Aboriginal paintings than I have,” Newstead says. “I know when a painting is assisted. I know how and when you can tell something’s inappropriate. And I know when something smells like a bad fish.”

One former arts centre worker says that when artists travelled down from the APY to paint in the Adelaide studio, there was a dramatic change in what they produced. Frail and elderly painters were completing large canvases. In other cases, artists with limited painting experience would be “producing these giant masterpieces with highly intricate designs … very sophisticated paintings … anyone who has any artistic experience will go, ‘Wow, that’s a bit miraculous!’”

Powerful friends

For all the allegations, O’Meara and the board are steadfast in their denials that white staff contribute in any way to the artistic process. And they have some powerful voices of support.

Quilty told The Weekend Australian: “If Skye O’Meara can honestly make works that are so truly unique then she must be applauded as probably the most talented artist on the face of the planet.”

The Archibald Prize winner writes that he has visited the APYACC’s studios more than 30 times over the past decade and has never witnessed staff interference, nor heard of it from artists.

He later sends an impassioned email, defending O’Meara: “To watch APY go stratospheric over the last decade has been one of the greatest honours of my life. To see vulnerable humans begin to communicate with the world and then to master and direct visual language in some of the world’s greatest art museums has been life changing for me and for them.”

While Quilty does not believe white staff worked on the paintings, he says it is standard practice, across the world, even in his own studio, for assistants to help in the construction of an artwork.

“Some artists do not even lay brush to canvas, instead using assistants to completely realise their conceptual ideas,” he says. But, he adds: “The truth is Skye never touches the paint.”

Marshall says the APY Lands are an intensely political place, “and that this is often a cause of lost opportunities for Anangu”. He adds: “I know Skye to be a woman of incredible passion and integrity with an excellent work ethic.”

At a meeting with The Weekend Australian in Adelaide, the board of the APYACC forcefully states there was never any white interference in Indigenous art. When asked if there was ever an instance where a white studio staffer would paint on an Indigenous canvas, contributing to the artistic process, Scales says: “We wouldn’t allow it. It’s our work. This is our bread and butter. One of your claims is insinuating this is fraudulent … These are made from our own hands. These are made from our thoughts and our processes, our Tjukurpa.”

Another board member adds: “We got hands to do it ourselves.”

Scales claims there is sexism towards O’Meara: “People look at the way women lead and if the women are assertive and holding a space, that’s a problem for men … if you’re a successful woman that’s problematic.”

When The Weekend Australian first contacted O’Meara with a list of questions, we heard, initially, not from her, but from Sue Cato, of the crisis communication firm Cato & Clive. We were also contacted by Lisa Slade, deputy director of the Art Gallery of South Australia. They both defend O’Meara and her good works.

Slade says: “I have never seen or heard anything of this (interference) in the 13 years that I have worked closely with Anangu (artists).”

O’Meara had contacted us last year, wanting to talk, but our investigation was not at a stage where we were ready to put questions to her. When we did, it took more than a week for O’Meara to respond. However, within a short time of us sending her those questions, emails began arriving from arts centres in the APY Lands associated with O’Meara’s APY Collective. The emails contained letters that were remarkably similar; they all supported O’Meara. The Weekend Australian has made no allegations about any of these arts centres apart from Tjala.

O’Meara is very ambitious, and often abrasive. One former staffer describes the dressing-downs she claims O’Meara regularly delivered to her as being “like a verbal drive-by shooting – it comes from nowhere and she doesn’t give you a chance to respond”.

She has clearly made many enemies and the board claims these people are motivated by revenge.

The board claims there is a conspiracy against O’Meara involving: Sam Osborne, (a prominent figure in the APY community in Adelaide, who is an academic specialist in Anangu languages and remote education, and conducts an Anangu choir); the Ernabella Arts Centre (which is the oldest arts centre in the APY, and Australia, but has disassociated itself from the collective); private gallery owners; and a number of others. The collective and O’Meara claim Osborne wants to take over the collective. Osborne did not wish to comment publicly at this stage, other than to say the claim he wants to take over the collective is “ludicrous”. But, like a number of others, he says he is prepared to give sworn evidence in court if required.

Ernabella Arts chair Anne Thompson and her two predecessors – Alison Carroll (winner of the prestigious 2020 Red Ochre Award for her lifetime achievements in the arts) and Makinti Minutjukur – say O’Meara and the collective are correct in their assumption Ernabella Arts would like to see a change of leadership at the APYACC.

They issue a strong statement, condemning the management of the APYACC: “For many years we have been hearing stories about abusive and bullying behaviour experienced by Anangu at the APYACC. Artists have also said they ‘don’t know how to paint like that’ (when they return from painting in Adelaide) and that those ‘white women’ paint the paintings for them.”

Unpalatable practices

Artist Tjungkara Ken is one of the famous Ken Sisters. She paints between the studio at Tjala Arts and the Yanda studio at Alice Springs, and occasionally in Adelaide.

She claims there has long been a practice at Tjala of white interference and her sister, Young, is one of a number of artists whose work was interfered with. “When the white women try to paint on my canvas, I tell them off,” she says. She claims it also happens in Adelaide. Early in 2020, she and Young were presented with a large canvas, which they made a start on, before returning to Amata. Ken was later shown a photo of the finished painting. “I was thinking we only got that one half-finished and they should have called us back to finish it off,” she says.

She was in the Adelaide studio in 2021 when Young had eight “very large” canvases to complete. “She just kind of made some starts on these canvases and Skye came in and completed them,” Ken claims.

In 2021, Ken McGregor, a Melbourne collector, got stuck in the NT due to Covid and volunteered at the Yanda studio, outside Alice Springs. (Yanda is owned by Chris Simon, whom the APYACC claims is part of the conspiracy). Tjungkara Ken and some of her sisters were painting in the studio. McGregor printed out a copy of a work one had painted at APYACC’s studios.

He asked why the paintings at Yanda were so different. “They just said they didn’t do it,” he claims. They said they’d return to the studio and their half-finished paintings would be completed by white staff. “They were adamant about it,” he says.

And then we got the video from Tjala, seemingly confirming what Tjungkara Ken told us.

Immediately, there is absolute denial. In the letter from Palmer, she says: “To suggest that artworkers engaging in their daily duties of studio support at the direction of artists, is in some way interfering with Tjukurpa, not only shows a lack of understanding of culture/cultural practice, but is also insulting to the governance structures of Aboriginal-owned Art Centres, operating under the values of self-determination.”

She adds: “In the photo, I am holding one of the brushes of artist Yaritji Young while she paints with another brush … I absolutely deny that I am painting in this photo, I am holding an unused brush and a bucket of pre-prepared red wash that Yaritji has already used to lay down the tjukula (rockhole) and passed back to me.”

In a phone call with Young and her husband Frank, an APYACC board member, they deny that her paintings have ever been painted on by white staff. They say The Weekend Australian has been told lies. We then get a lengthy lawyer’s letter from the APYACC, describing what Palmer may be doing to the canvas as “background wash”, which it claims is an acceptable practice.

We contact two independent and experienced Indigenous art centre managers and describe in detail what is happening in the video. They are appalled. “This is just totally unacceptable,” says one.

O’Meara and her supporters validly argue that she’s provided much-needed income for the Anangu artists and their families. Her critics would argue it’s come at a great cost.

Anangu elder and celebrated painter, Makinti Minutjukur, tells The Weekend Australian she was once visiting Adelaide from the APY Lands when she went to the collective’s studio and she watched as O’Meara came in and painted on an Anangu artist’s work. “I was thinking that she is really taking their ideas and their knowledge,” she says, “and erasing it and replacing it with hers.”

Minutjukur says the great art comes when artists are able to contemplate and connect with their Tjukurpa without interference. “It gives them an immense sense of pleasure and joy – doing it for themselves in that connected way … Tjukurpa is not a space you should be coming in and interfering with,” she says.

Statement from APYACC

In a statement posted on the organisation’s Instagram account, the APYACC denied it had interfered with artists’ Tjukurpa, and said that some photos and videos were not put to the APYACC.

It also denied that manager Rosie Palmer of the outback Tjala Centre – a member of the collective – was unduly interfering in famed Indigenous artist Yaritji Young’s painting in a video supplied to The Weekend Australian.

“The photo in question shows the application of a background wash, which in Yaritji Young’s case is the last stage of this underpainting process,” the AYCACC statement reads.

“It is in no way interfering with the artist’s Tjukurpa [her ancient and sacred stories of customs and law] or out of the ordinary for an art assistant to take part in the process, including slopping or spraying the wash on the canvas at this stage, at the artist’s direction, Indigenous or otherwise.”

This comes after Ms Palmer denied, for The Weekend Australian’s original report, that she was painting when shown a still of the video.

The statement said she “correctly denied painting in the photo shown to her”.

The statement did not address allegations made of APYACC administrator Skye O’Meara by Indigenous artists Paul Andy, Derik Lynch, and another who chose to stay anonymous that Ms O’Meara would paint on their artwork.

APYACC said it had “previously written to The Australian on multiple occasions to seek to engage with them on the role art assistants play in all contemporary, professional art studios producing world-class art, Indigenous or otherwise.”

“APYACC does not hide the fact that art assistants assist in the underpainting process. The video taken was in the open air, in the presence of guests, at a time when Tjala Arts knew it was being investigated by The Australian.”

“True industry experts understand the line between assistance at artists’ direction and interference with the artistic process and know that APYACC has never crossed this line.

“It is grossly offensive to the many hundreds of proud Anangu who work with APYACC to suggest otherwise, or that they would tolerate their Tjukurpa being interfered with.”

gregbearup@proton.me

The Australian makes no allegations about work produced in the seven arts centres on the APY Lands, apart from Tjala.

The Australian does not raise any allegations against any of the artists themselves or suggest those speaking in support of O’Meara and the Collective are saying anything other than what they have been told and believe to be the case.