We emerge from the desert in a posse of Toyotas to an ambush. The entire mob of Kaltjiti, a tiny remote settlement in the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands of South Australia, has gathered to meet us – or more specifically, to greet her. She descends from the LandCruiser with her Prada sunnies perched high and a pearl dangling from each ear. She’s dressed beautifully in a black dress with a blue shawl wrapped around her shoulders to ward off the unseasonal chill. She carries a smart pink handbag. She’s small and elegant like a black Audrey Hepburn. The women, especially, are in awe of this stylish boss lady who shares their Indigenous DNA. She’s hustled into the prime plastic chair, set forward from the crowd. She insists they move her back among the mob. Women press their faces to hers.

It’s obvious there’s been much preparation but still the reception is wonderfully chaotic. Mongrel dogs with dingo blood wander across the red desert stage. Kids on pushies chuck wheelies and skids. People shout instructions and orders in chirpy Pitjantjatjara. She’s handed a loudhailer and greets the crowd to great cheers. Old men in cowboy hats and with faces as black as plums start the ceremony proper with their mesmerising clapping sticks. They’re joined by the haunting, soulful chants of the older women.

It’s then that Aunty Nyukana Norris appears from her hiding spot behind a HiLux. Mrs Norris, as she’s known, has a great sense of drama and pathos. Her skinny legs poke out the bottom of her skirt. Her wild, grey hair is blown forward around her face. She has grey stubble on her chin. Mrs Norris points to the heavens and howls and sings. At one point she stops, mid-performance, and gives her fellow singers a serve in Pitjantjatjara, demanding they lift their game in accompanying her. They oblige and the volume rises. The dance she is performing today is about the black-footed rock wallaby, endangered in these parts, hunted almost to extinction by feral cats and foxes. Wallaby from here were taken away and into a captive breeding program. The dance is an allegory for the Stolen Generations.

The woman in the chair, watching, was not so much stolen as given away in shame. Her face is a kaleidoscope of emotions. Smiles and tears. Joy and heartache. Linda Burney has led a remarkable life. It has led her here, seated in a plastic chair in the desert as the Minister for Indigenous Australians being welcomed by song to Kaltjiti country by Mrs Norris. Everything Burney’s done and all she’s experienced – the joy and many triumphs, grief and immense suffering – have brought her to this point in history where her old friend, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, has chosen her to sell one of his most treasured policies, an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. If she’s successful, the Voice will be enshrined in the Constitution.

And now her moment has come. Her own story has instilled in her a resilience and a perspective that few others possess. She will draw on this as she seeks to write a new chapter for Indigenous Australians. She’s tramping the continent, promoting the concept – its principles, if not a fully fleshed-out form of words – and listening.

Since Federation, only eight of the 44 proposals to amend the Constitution have passed muster with Australian voters. Can Burney make it nine by convincing a majority of Australians in a majority of states that we should amend our founding document to acknowledge that a culture existed here for thousands of years prior to British colonisation? Can she persuade the nation that the Indigenous communities of Australia need a bespoke seat at the table, advising Parliament?

She must satisfy all Australians that the Voice, when finally constituted, will make a difference to the lives of people living in poverty in Wilcannia, in Cherbourg, on Erub Island, in Maningrida, in Fitzroy Crossing and Kaltjiti. Her task includes confronting the objections raised by other indigenous figures with a national profile. Warren Mundine, former national president of the Labor party, says race-based constitutional rights don’t work. Northern Territory Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price says the Voice would mean “propping up another bureaucracy”.

Can Burney get Australians to vote for the benefit of those Noel Pearson describes as “a much unloved people … the ethnic group Australians feel least connected to”? In his 2022 Boyer Lecture, Pearson pointedly frames the referendum as a test of non-Indigenous attitudes to indigenous Australians, and says that “despite having never met any of us and knowing very little about us … Australians hold and express strong views about us, the great proportion of which is negative and unfriendly”.

What is shamefully true is that wherever Indigenous people are living in their communities on this continent and on its islands there is overcrowded, substandard housing; there are poor education outcomes for children, violence is rife, unemployment is high, disease is rampant, and they are jailed in shockingly, disproportionately high numbers. They die years earlier than most other Australians. How will Linda Burney convince Australians that an Indigenous Voice will lead to better outcomes for Aunty Nyukana Norris and her grandkids, living in the remote tribal lands of South Australia?

Burney arrives at the charter hangar on the outskirts of Adelaide Airport in a fluster, but in good humour. She’s had a wardrobe malfunction. The sole on one of her chunky pink sandals has come loose and is quacking as she walks in for the pilot’s safety briefing. “This is a disaster,” she says, unzipping her suitcase in search of replacements. “These are bloody Edward Mellers!” Reshod, we board a small plane in howling winds for the long and bumpy flight to the APY Lands.

With the Adelaide Hills beneath us, Burney, 65, chats about her childhood in the don’t-blink town of Whitton in the NSW Riverina. She was raised by her spinster great aunt, Nina, and her bachelor great uncle, Billy. They were, she says, wonderful and loving people who instilled old-fashioned values of “honesty, loyalty and respect” and pushed her to get educated. Billy was a drover, a shearer and a farmhand and she talks of a bucolic childhood of poddy calves, horses, slug guns, swimming in the irrigation canals and the great thrill of fish and chips and soft-serve ice cream when they drove into Leeton, once a month, for the big shop. They lived in a shack with no running water inside, only one power point and an outside long-drop. “But they raised me with the most outstanding values, and a lot of love,” she says. “They were my parents.”

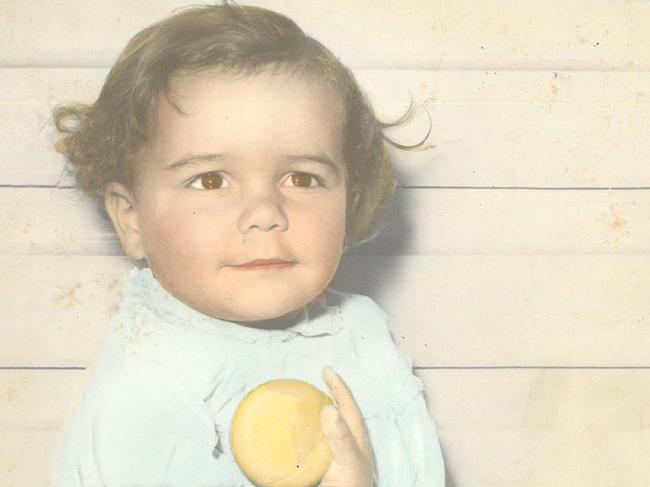

Aged four, Burney remembers looking at a photograph of her and her cousins. “They were all blond-haired and blue-eyed, and there on the side of this family photograph is this smiling little black girl. I lived outside all summer, and so I was very black,” she says. “And that’s when I realised, ‘Oh, I must be Aboriginal’. ” Just who her father was would remain a secret for many years. The truth was buried deep within a great pile of family shame.

Her mother, who was white, had fallen pregnant to an Aboriginal man. She skipped town to escape the scandal, and Billy and Nina, her mother’s aunt and uncle, took in the illegitimate black baby, Linda. “It’s only been in the last 15 years or so that I’ve realised how brave that was, that this great aunt and uncle in their 60s, neither of them had ever married, would take on an Aboriginal baby, born out of wedlock,” she says. “I’m sure they suffered socially … I went back for the 150th anniversary of the Whitton Public School. I was a NSW cabinet minister at the time and probably one of the most successful people to come out of Whitton, and this fellow from school came up to me and said, ‘The day you were born was the darkest day this town has ever seen.’ I was stunned. I couldn’t respond and so I just walked away. The fact that he could say that after 50 years brought home the cruelty and the racism and the small-mindedness of some people in that town.”

Burney tells this story to highlight the bravery of Billy and Nina, and it says something about the way she views the world that she chooses to focus on the positive, the stoicism of Billy and Nina, rather than the negative, being left by her mother at the hospital where she was born, she tells me as the plane lands in Coober Pedy to refuel. She always knew her mother – and expresses no bitterness towards her – but they never had a close relationship and she never mentions her name, not to me and not in previous interviews. She went to live with her for a while, “but there was too much water under the bridge”. (Her mother had more kids – her siblings, with whom she’s in contact – and died of a burst appendix at the age of 49.)

Her early years were idyllic but her teenage years were not. At the age of 13 Linda took on the role of carer as Billy and Nina’s health declined. She would haul water into the house to bathe them. She nursed them both until they went to hospital to die – Billy when she was 15, Nina the following year. She had a best friend, Barbara Smith, and after the deaths of Linda’s de facto parents, Barbara’s mum – a single white mother who worked as a school cleaner – took her in. “They didn’t have much, and so it was an incredibly generous thing to do,” she says. “They became my family, I’m still very close to them.”

Burney says that from the age of 12 or 13 it began to dawn on her that she was Aboriginal and she set about trying to decipher what that meant. Not that she was ever allowed to forget. In the school yard she was called “darkie” and a “smelly boong” and at 10 a white woman in Whitton told her she’d never amount to anything because she was black. She was teased, too, for not having a father. “It was a time when people denied they were Aboriginal,” she says. “It was much easier for them to say, ‘I’m Spanish, or Indian’ or something. I used to imagine that I was walking down a road and I’d come to a fork and I could walk one way or the other. I could deny who I was, or I could choose the other road, and that was a much more difficult road, and that was the road of truth. That’s the road I took.” She began to embrace being Aboriginal, learning what she could about her culture. “But there was still a big part of the jigsaw that was missing. I didn’t know my [Aboriginal] family and I didn’t know my father, but the acceptance was there.”

Commentator Andrew Bolt has chided her for this. “Burney’s mother was of Scottish background and she was raised by her Scottish great aunt and uncle,” Bolt said recently on his TV show. “She didn’t meet her Aboriginal father until she was 28. I’ve discussed this stuff with Burney at length. She said it was not until she was 13 that she embraced her Aboriginal identity, which to me suggests a choice to identify with one side of her heritage rather than the other.”

To this, Burney says: “There is no choice. You are either Aboriginal or you are not, and people treat you in certain ways [because of it]. And for Andrew to say something like that just shows he doesn’t understand what Aboriginality is.” In an even tone, she adds: “You can either let that make you cross and pull you down, or not,” she says. “To say it doesn’t worry me is wrong. But it doesn’t diminish me. It only makes me more determined.”

She searched for years, writing letters and asking around, to find her black family, the task made more difficult because no one on the white side was prepared to fill in the blanks. Her maternal grandmother, Amelia, lived in Whitton and when she was on her deathbed, and with dementia, Linda asked her who her father was. “She just snapped into clarity and said, ‘You don’t need to know that.’ It just showed me how entrenched it was and it showed the shame that my mother must have brought onto that family, having a black baby.”

Burney’s great advantage was that she was very bright. Kindly teachers at her school saw her potential and insisted she stay on when she’d wanted to quit school, aged 16 and deep in grief after the deaths of Nina and Billy. She won a scholarship to study at Mitchell College in Bathurst. “I did [some units of] Aboriginal studies, which was a massive emotional experience for me.” She was the first Aboriginal, “or the first to identify”, to graduate from the college. It began a run of firsts. She became a teacher in western Sydney and was soon noticed by the department and drafted to work on Indigenous education programs.

She rose quickly and soon became the boss of the NSW Aboriginal Consultative Group, which led to Aboriginal studies to be introduced into schools for the first time. She was the driving force behind the Walk for Reconciliation in May 2000, when about 250,000 people tramped across Sydney Harbour Bridge. She was appointed director-general of the NSW Department of Aboriginal Affairs and has sat on the boards of SBS, Anti-Discrimination NSW, the NSW Board of Studies and the NRL Indigenous Council. She’s spoken at the UN and advised premiers on juvenile justice. In 2003 she was elected to the NSW Parliament, the state’s first Indigenous MP, where she held various portfolios, including Deputy Leader of the Opposition. And then, in 2016, she was elected to Federal Parliament, becoming the first Indigenous female member of the House of Representatives. In June, she was sworn in as Minister for Indigenous Australians.

“There is no choice. You are either Aboriginal or you are not, and people treat in certain ways”

Ross Fitzgerald, a historian and columnist for The Australian, says Burney is “much underestimated”. “People seem to forget what a fine politician she is,” he says. “Before she entered politics she had an extremely successful career as a bureaucrat … she is able to raise issues in a non-confrontational but very direct way.”

The Nationals’ chief brawler, Barnaby Joyce – a political foe – expresses deep admiration for Burney, and some insights. “She’s a very warm and decent person,” he says. “People like her, who’ve travelled a lot of dry gullies, have empathy … we have very different political outlooks but I’ve never had her snarl at me because of that.”

Burney may have grown up in a “white family” but hers has been a story of violence, disease and death – and she shares this with the people of the APY, and so many other mobs. Her professional successes have come despite, and during, the almost relentlessly cruel hand she was dealt in her personal life.

Burney eventually found her father, Noni, when she was just shy of her 28th birthday and eight months pregnant with her son Binni. It felt, she says, as though a place had always been set for her at the family table, waiting for her arrival. It came after years of detective work, and help from Aboriginal friends, narrowing the possibilities down to two brothers who lived in Narrandera, a 45-minute drive from Whitton.

On that day in 1984, when Noni was visiting Sydney, she was picked up from her house in inner-west Newtown by an Aboriginal friend. “I can’t remember where we went, but I was very pregnant and I was wearing a blue dress and white shoes,” she says. “Noni came out and he was wearing a blue denim shirt and a big black Akubra.” He got into the back of the car with the heavily pregnant stranger. “I told him my mother’s name and he couldn’t remember it. I then showed him a photo of her at about the time they’d have met. He looked at it for a long time and then he embraced me and said: ‘I hope I don’t disappoint you.’ He was flying back to Narrandera so I went with him out to the old Ansett terminal and chatted with him for a couple of hours while he waited for his plane.” She learnt that Lawrence “Noni” Ingram was a musician with his own band and had worked as a fruit-picker and council worker. She also discovered she had 10 more siblings. There was a brilliant red sunset. “I had my son the next morning and his second name is Dironbirrong, which means ‘red sunset’ in Wiradjuri.”

It was a bright spot in a bleak history, beginning with the deaths of Nina and Billy and the early deaths of her mother and brothers and sisters, black and white. She’s spoken in the past about relationships where she was a victim of domestic violence. She left one long-term relationship, having suffered a broken nose and broken eye socket, fleeing with her two small kids and one suitcase.

But it was other blows that nearly felled her.

In the mid-’90s Burney met the great love of her life, Rick Farley, the former National Farmers’ Federation executive director, a key figure in the passage of native title laws. It was, her friends say, a beautiful, loving relationship. On Boxing Day, 2005, Farley was in the back garden of her Sydney house, by the geraniums near the pool, when he sang out, asking what they should do with the Christmas leftovers. “Chuck the oysters and keep the prawns,” she said. He suddenly keeled over, suffering a brain aneurysm. He never recovered and died five months later after falling out of his wheelchair. And then, in 2017, after a long struggle with mental illness, her 33-year-old son Binni, born after the brilliant sunset, died by suicide in the same house her husband had his aneurysm.

Burney has crossed vast barren wastelands of grief and despair, rather than mere dry gullies. All her friends tell me they’ve no idea how she managed to go on at times. “She has overcome extraordinary adversity and trauma in her life,” Prime Minister Anthony Albanese tells me. “And yet she is someone who is always thinking of others. She’s a remarkable human being, and I am honoured to call her a friend.” He says he chose her to be his chief spokesperson for the Voice because “Linda is someone who brings people with her on the journey. This needs to be the moment that unites the nation and Linda always seeks to bring people together, rather than to divide people”.

Burney is able to straddle great divides, having seen the world from so many perspectives. She has an easy relationship with Barnaby Joyce because she grew up in a house that provided the fencers and shearers who toiled on Joyce’s inherited spread. She can relate to people living in the “weatherboard and iron” in the bush. She’s lived in the city, and is comfortable talking at a university or a Rotary club. She can command a classroom full of kids and a boardroom full of egos. She can navigate the bureaucracy, and spot when wool is being pulled. Veteran NSW Labor politician Meredith Burgmann says one of Burney’s great political skills is “keeping everyone in the cart”, which she did, aptly, in the unenviable post as Deputy Leader of the Opposition in NSW.

She will need this skill to sell the Voice in the face of arguments that the proposal is tokenistic and too light on detail to take to the nation. The Voice to Parliament grew out of the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart. The notion is that representatives from Indigenous communities around Australia will advise Parliament on issues that affect Indigenous communities through a Voice enshrined in the Constitution. Burney’s visit to the APY lands is part of a long consultation process that will determine exactly how it operates and the form it will take ahead of legislation. “I want The Voice to be owned by the Australian people,” she says.

Over the next year or so, until the referendum, Linda Burney will be traipsing the continent, speaking to farmers and farriers, teachers and truckies, bankers and black folk. Between Parliament and Cabinet she’s been to Adelaide, APY, Uluru, Alice, Darwin, Western NSW and the Torres Strait, and will soon do a big sweep of WA, and the Top End after the wet season. She’s trying to bring us all along with her. She’s urging Australians, as she sees it, to take the road of truth.

As the aircraft approaches the remote desert airstrip, the turbulence tossing her tiny frame around in the seat, she tells me there’s been no one intimate in her life since the death of Rick Farley. “Not even a date!” she says incredulously. I ask if she’s ever considered giving it all away and retiring to her beloved garden. “Never,” she says. “Never.” She’s always been able to compartmentalise her life, to separate the trauma from her work – “which is not always a good thing,” she says. Sometimes when she’s home alone she admits to completely falling apart. But she always manages to pull herself together, slip into a pretty frock, put on some lippy and pearls and face the new day, even if her shoes occasionally let her down. Our little plane bounces down through clouds and onto the dirt runway in the APY. A posse of Toyotas is waiting.

Umuwa, up near the Territory border in the centre of Australia, is the administrative centre of the APY Lands. It was built in 1991 to house the government workers and depots that service to 2000-odd Indigenous folk spread across the 20 communities of the APY, an area the size of Germany. It is one of the most sparsely populated and remote places on Earth, outside the poles. The local Federal electorate office is literally half a continent away, down on the coast at Port Augusta – much further than the drive from Sydney to Brisbane. The average life expectancy for people in the APY is 53.

Burney has come here for a series of meetings with locals at the APY Trade Training Centre. She listens and then asks blunt questions. Do you have a good supply of clean water? What happens with people who need dialysis? “In some communities there is no clean water for dialysis,” she says to the delegation. “It is shameful.” One of the big problems, she’s told, is that there is no state services office in the APY Lands and so it is extremely difficult for people to get identification, just to prove who they are. “You need 100 points of ID to get ID. That’s extremely hard because a lot of people don’t even have a Medicare card.” It means people can’t register to vote, open bank accounts, get a licence or get the certificates required for working with children. Staff will spend hours on the phone with the banks trying to get people’s bank accounts activated. “I don’t think people in mainstream Australia have any idea how few of our people actually have birth certificates,” Burney says.

Basic services that most Australians take for granted are non-existent in the APY Lands. She’s told there is no mortuary service. Bodies are left in the living room of the family house, sometimes for many days, until relatives and friends can travel for the sorry business. At nearby Ernabella Anangu School we walk into a classroom of primary school kids where the teacher has a microphone around her neck to amplify her voice because many of the kids have poor hearing as a result of severe middle-ear infections.

At a meeting of young leaders Burney talks about the Voice and how it will allow the representatives from APY to raise some of the issues we’ve seen with the government in Canberra. Inawantji (Ina) Scales, a fiery and articulate young woman, wants to know how the voice of the APY mob will be heard, “because the voices of those mobs in the eastern states are always louder”. Burney hints more at the form the Voice will take: “It’s who you choose to be your representatives, it’s their job to bring your voice.” Will it be selected or elected, Ina asks. “The government will not be appointing people, it will be up to the communities to decide,” the minister replies. Ina says the younger generation in the APY “don’t really have a voice … the elders, they block everything for us and that’s a big worry.” Burney says that’s why she’s here, listening, to hear those concerns. She tells Ina provisions will be made to ensure there’s a gender balance and young people are represented.

Polls suggest a majority of Australians support an Indigenous Voice to Parliament. A Guardian Essential poll in August had two thirds of Australians in favour, as did a Resolve poll for The Sydney Morning Herald and The Age in September, which found 64 per cent in favour and 34 per cent against. Linda Burney’s job, as Meredith Burgmann says, will be to keep that 64 per cent of Australians who now agree in the cart.

Pearson, in the Boyer Lecture, says: “It does not and will not take much to mobilise antipathy against Aboriginal people and to conjure the worst imaginings about us and the recognition we seek. For those who wish to oppose our recognition it will be like shooting fish in a barrel. An inane thing to do but easy. A heartless thing to do but easy.” But as the objections of Mundine and Price reflect, she’s yet to convince even some of her own mob that the Voice will make a difference.

Frank “Riverbank” Doolan is a respected elder from Dubbo who works daily in his community. He is Wiradjuri, like Burney, and has known her since the 1980s, when they were both involved in Aboriginal politics in Sydney. He has enormous respect for her and believes she will be a very good minister. “There’s never been any doubt about Linda’s commitment and her contribution to her people,” Riverbank says. “She’s a fighter for her people, but she’s willing to compromise to get the best outcome.” But he doesn’t support the Voice. “At a community level I don’t think it will make any difference,” he says. “People will still grapple with abject poverty, persecution by police, poor rates of employment and even poorer education. If the Voice promises to heal all that, then that’s a great thing. I just don’t think it will.” He’d rather see the money spent on practical solutions at a community level.

“You’ve got to repay that faith that people put in you. That’s what I try to do every single day”

Burney says she completely understands Riverbank’s point of view. “This referendum will cost a lot of money, but I would say to people like Frank that we need to take a long-term view about things. The Voice will lead to Parliament making better decisions which will lead to better outcomes for our people.” Burney points to what happened in Riverbank’s home of Dubbo when Covid broke out in the Indigenous community in August last year. The Federal Government’s response was woefully inadequate. “The lack of coordination and the lack of understanding was astounding,” Burney says. “We had three very experienced Aboriginal people in the Labor caucus and the Morrison Government just wouldn’t listen to us,” she says. Had there been the Voice, she says, the response may have been very different.

And then she says: “There are two worlds in Australia – there’s mainstream Australia and then there’s Aboriginal Australia. In mainstream Australia things that we expect as being normal are not out here. Having clean water is normal, but not out here. Paying $8 for two litres of milk is not normal, but it is out here. People having to put the bodies of loved ones in their living rooms, waiting for burial, is not normal in mainstream Australia.” She is well aware of the immense problems in these communities. “But addressing these problems will not be solved by some bloody silver bullet from Capital Hill,” she says. “It is working on the ground with these communities and being culturally aware, and part of that is knowing the history and understanding that what shaped Aboriginal Australia is not what shaped the rest of Australia.”

Having people identify problems in their own communities, and bringing this to the attention of the Parliament through the Voice, will be a much better system, she argues, than the one we have.

Not long after we leave Kaltjiti I ask Burney how she felt, sitting in that plastic chair as Mrs Norris was dancing towards her, welcoming her onto country. “Well, as we were approaching, I saw that there were a lot of cars and the woman who was interpreting for me explained that they were going to do a ceremony for me and she explained the meaning. So when I heard the wailing, which was about the kids of the Stolen Generation, it was extraordinarily powerful. I felt a little speechless and very honoured.”

She adds: “I just see myself as someone who is part of the struggle, but then you have these moments where you realise people see you as a leader and treat you respectfully. And there’s reciprocity in that, and you get a very deep sense of the gravity of the position you hold and what that means to the broader Aboriginal community. You’ve got to repay that faith that people put in you. And that’s what I try to do every single day.”

More Coverage

Greg Bearup is a feature writer at The Weekend Australian Magazine and was previously The Australian's South Asia Correspondent. He has been a journalist for more than thirty years having worked at The Armidale Express, The Inverell Times, The Newcastle Herald, The Sydney Morning Herald and was at Good Weekend Magazine before moving to The Weekend Australian Magazine in 2012. He is a three-time winner of the Walkley Award, and has written two books, Adventures in Caravanastan and Exit Wounds, written with Major General John Cantwell. He is also the creator of the hit podcast, Who The Hell is Hamish?

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout