Yunupingu: the great voice of his people

One of Yunupingu’s final conversations about Indigenous affairs was with Anthony Albanese, who gave him a personal update on the voice.

Yunupingu, the great leader who helped usher in the nation’s first land rights laws, has died as Australia prepares to vote on the constitutional change he fought for.

One of Yunupingu’s final conversations about Indigenous affairs was with Anthony Albanese, who phoned the 74-year-old at his home in northeast Arnhem Land on March 23 to pay his respects and give him a personal update on the voice.

During the phone call, Yunupingu was surrounded by family when he told the Prime Minister: “You were truthful.”

Mr Albanese paid tribute to Yunupingu on Monday, saying he “walked in two worlds with authority, power and grace, and he worked to make them whole — together”.

“A man who stood tall in his beloved country, and worked to lift our entire continent in the process, Yunupingu understood a fundamental truth: if you want to make your voice count, you have to make sure that it’s heard,” he said.

The leader of the Gumatj clan’s advocacy for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people spanned seven decades and 16 prime ministers, starting when he was 15 years old.

From the Yirrkala bark petitions to the aftermath of the Mabo decision, he was the defining figure of the land rights movement. As he grew in stature and influence, the prime ministers came to him.

In the past two decades, he was an important force in the push for constitutional recognition and Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney said success in the voice to parliament referendum would be devoted to Yunupingu’s memory.

In 2016 Yunupingu wrote that “the Australian people know that their success is built on the taking of the land, in making the country their own, which they did at the expense of so many languages and ceremonies and songlines – and people – now destroyed. They worry about what has been done for them and on their behalf, and they know that reconciliation requires much more than just words. So the task remains: to reconcile with the truth, to find the unity and achieve the settlement.”

Yunupingu had spoken with Mr Albanese about the voice last July, when the Labor leader chose Yunupingu’s Garma festival to announce a draft wording for the voice referendum question and the proposed constitutional amendment.

Yunupingu – who had long experience of politicians saying one thing and doing another – was heard to ask Mr Albanese: “Are you serious this time?”

Mr Albanese replied: “Yes, we are going to do it.”

On Monday, Mr Albanese’s predecessors – from Paul Keating to Scott Morrison – paid tribute to one of the nation’s greatest men.

Yunupingu’s daughter Binmila described him as “the pathmaker” in a touching tribute published shortly after his death on Monday morning.

“The loss to our family and community is profound. We are hurting, but we honour him and remember with love everything he has done for us,” Binmila wrote. “We remember him for his fierce leadership, and total strength for Yolngu and for Aboriginal people throughout Australia. He lived by our laws always.”

Binmila said her father “was born on our land, he lived all his life on our land and he died on our land secure in the knowledge that his life’s work was secure”.

He had friendship and loyalty to so many people, at all levels, from all places.

“Our father was driven by a vision for the future of this nation, his people’s place in the nation and the rightful place for Aboriginal people everywhere,” she said.

The leader of the Gumatj clan in northeast Arnhem Land was just 15 when he helped draft the historic Yirrkala bark petitions opposing mining on the land of his Yolngu people. After attending Bible College in Brisbane, he was a court interpreter for the Yolngu in the landmark Gove land rights case held when the government ignored bark petitions.

When the Yolngu lost that case, he advised on the nation’s first Indigenous land rights laws in 1976. Yunupingu played a role in every chapter in Indigenous affairs since Robert Menzies was prime minister. Many of the nation’s leaders would come to him and to his Garma festival of Indigenous culture held annually at Gulkula. Yunupingu made Garma the most important event for Indigenous policy discussions.

Yunupingu was the inaugural chairman of the Northern Land Council after the laws he helped devise gave Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory rights over their land. He was Australian of the Year in 1978 and declared a national living treasure in 1998. After the High Court decision on Mabo, Yunupingu convened a historic meeting of leaders at Eva Valley then presented the Eva Valley statement to Paul Keating calling for commonwealth legislation and a native title act.

In 2007, Yunupingu’s persuasive call for constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians coincided with a decade of bipartisan work on the issue. The result is the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart. He had been advising the government on the voice as a member of its referendum working group.

On Monday Ms Burney said: “I want to dedicate what will be a successful referendum at the end of the year to Yunupingu. It is hard to put into words what this loss means for this country … But his legacy, his inspiration, will live on.”

Yunupingu died at his home in Gunyangara. At 74, he was a grand age in a region where men die much younger than non-Indigenous Australians. In recent years Yunupingu’s health had begun to fade. He had had a kidney transplant.

Indigenous academic Marcia Langton, a friend of Yunupingu since 1977 and one of his collaborators, said he was the greatest leader Australia had ever known. “He loved his country and his culture, and held his ceremonial responsibilities as the highest priority,” she said.

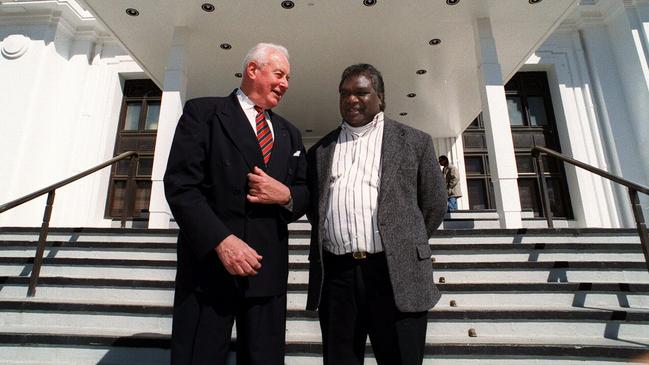

Fred Chaney – Aboriginal affairs minister in the Fraser government after Yunupingu helped usher in the nation’s first land rights laws – said it was impossible to exaggerate the clan leader’s influence.

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout