I offer my heartfelt condolences to all his family. Indeed, I send my condolences to all Aboriginal people in Arnhem Land and beyond who will be touched and deeply saddened by the death of Yunupingu. His legacy is immeasurable and will endure in the memory of the Australian people, especially the Yolngu people, for generations.

Yunupingu was exposed to the business of politics as a young man, when he was recruited by his father – also a much-respected leader of the Gumatj clan – to help compose and translate the famous Yirrkala bark petitions.

The petitions were sent to our parliament in August 1963, and they remain on permanent display in the public area of Parliament House in Canberra. The petitioners sought an inquiry into the commonwealth government’s decision to excise thousands of hectares of Aboriginal Reserve land on Gove Peninsula for a bauxite mine.

The language and interpreting skills of the young Yunupingu were called on again in the late 1960s, when the Yolngu people continued their challenge to the mining lease through the Northern Territory Supreme Court. Their case was led by barrister Edward Woodward, and the proceedings relied very much on Yunupingu’s translations.

The Yolngu challenge was unsuccessful, but it stirred the resolve of Gough Whitlam to legislate for land rights in the Northern Territory.

Yunupingu went on to be an early office holder of the Northern Land Council, one of four land councils created under the Northern Territory land rights act, which was finally passed in 1976 by the Coalition government led by prime minister Malcolm Fraser. Yunupingu chaired the Northern Land Council on and off for more than two decades from its early days until 2004, and I was director of the Central Land Council for some of that time.

He showed himself to be a canny and forceful operator on those occasions when we teamed up to take on governments intent on diminishing the powers of the traditional owners whom the land councils represented. He weathered tempestuous engagements, never nervous about defending his patch and the rights of traditional owners. Those of us old enough to remember will never forget the occasion in 1997 when he clashed with Northern Territory chief minister Shane Stone.

Yunupingu had told the National Press Club in February that year that he would use international outlets to complain about Australia’s record of Aboriginal deaths in custody and the Howard government’s plans to amend Paul Keating’s Native Title Act.

In response, Stone said he had difficulty with people who were disloyal to their own country. Yunupingu was “just another whinging, whining carping, black”. Yunupingu retorted that Stone was a “paternalistic redneck”. For the record, it was to the credit of both that they were able some years later to put the clash behind them. For a while, they even joined together in a mining business.

Land councils have often been accused – wrongly, in my view – of being implacably opposed to mining on Aboriginal land. But Yunupingu was always open-minded about mining. He appreciated the benefits for Aboriginal employment that the industry could deliver. But he was also ready to hold the industry and governments to account. During his lifetime, Yunupingu was showered with honours and awards. In 1978, aged just 29, he was named Australian of the Year in recognition of his role in negotiating the agreement for the Ranger uranium mine in Kakadu National Park.

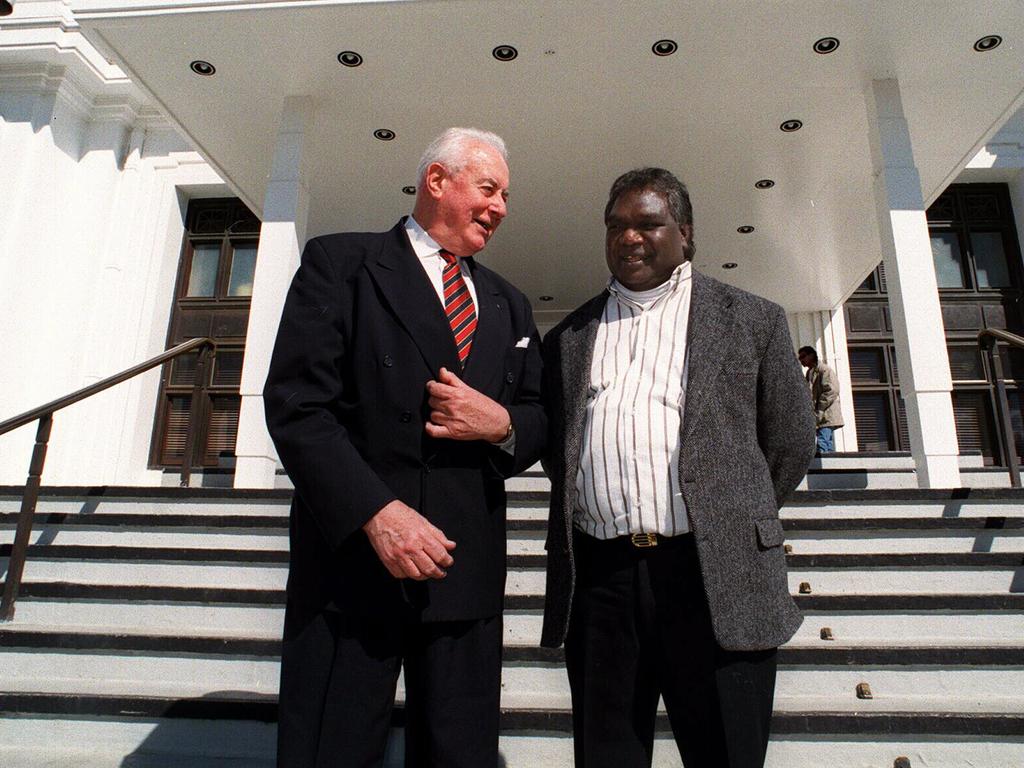

Yunupingu’s advocacy reached beyond land rights. He had an abiding commitment to reconciliation, recognition and treaty. In 1988, the year of Australia’s bicentenary, he had a leading role in the creation of the Barunga Statement and its presentation at the annual Barunga Festival to prime minister Bob Hawke. Hawke responded to the statement by publicly proclaiming that there would be a treaty with Australia’s First Nations people. Yunupingu was not alone in his disappointment about the Hawke government’s failure to deliver on the promise of treaty – or, indeed, about its failed commitment to national land rights. But he continued to press his cause for recognition.

When prime minister Kevin Rudd took his cabinet to East Arnhem Land in July 2008, Yunupingu presented him with another bark petition, this time seeking the recognition of Aboriginal people in the Constitution.

The Albanese government last year recognised Yunupingu’s standing when it appointed him to the First Nations referendum working group, which has been advising us on how best to ensure a successful referendum later this year. Unfortunately, he was unable to participate directly in meetings of the working group because of his declining health.

But I do know he was following closely the progress of the working group’s deliberations and advice. He knew that a successful referendum would be a catalyst for a fundamental change in this country – a change in how we looked at ourselves, a change in how others looked at us.

In 1998, delivering the annual Vincent Lingiari Memorial Lecture in Darwin, Yunupingu reflected on the need for change: “A country which lives the lie that it is a spontaneous creation of one or more European peoples, a grand expanse of opportunity created in a generous fit of reason, while the original inhabitants remain scattered around the fringes in poverty or are hauled in to the jails as the result of the destruction of their societies, laws, self-governing arrangements, and culture by the European newcomers … such a country cannot bear the scrutiny of its own citizens, let alone the rest of the world.”

After that, Yunupingu observed: “A constitution should be about the rights of the people, not the powers of government.”

I want to conclude by quoting from the citation that the University of Melbourne wrote when it conferred on Yunupingu an honorary doctorate in 2015.

The award was in recognition of a fire that the citation said Yunupingu had lit within Australia – “a fire that will blaze ever brighter until Indigenous people secure their self-evident rights to property, their own way of life, economic independence and control over their lives and the future of their children”.

Senator Pat Dodson is the Special Envoy for Reconciliation and the Implementation of the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

Yunupingu was a man of high degree, an esteemed cultural, ceremonial and political leader, and a powerful advocate for land rights and the unique standing of Aboriginal people in the Australian nation.