Yunupingu: an Indigenous icon, land rights campaigner

Yunupingu was a titan of the Aboriginal rights movement, distinguished by his charisma, leadership and pride.

When Yunupingu was about 16 years old, he stood beside a banyan tree in the remote northeast Arnhem Land community of Yirrkala and watched his father cry. It was the first time he had seen the old man weep. Mangurrawuy Yunupingu, a fabled warrior, Gumatj clan leader and compatriot of the great Wonggu — a Djapu chieftain who, together with anthropologist Donald Thompson, ran resistance against the Japanese during World War II — was visibly angry. The banyan tree contained sacred Yolngu beliefs, yet it was about to be damaged by a mining company. It was the first time Yunupingu had seen men of his father’s generation, men who held life and death in their hands, unable to enforce their will on their own land. “We began our fight that day,” Yunupingu recalled in a speech memorialising the Gurindji land rights activist Vincent Lingiari in 1998.

Yunupingu was born on June 30, 1948. He passed away on April 3, 2023. He will be remembered as an icon who campaigned for Aboriginal land rights and economic development to stop his people “drifting off with the tide”, and also as the face of Garma Festival. Yunupingu was the chosen son of a powerful leader with 11 wives. His first name, which his family has asked is no longer used, meant “the area on the horizon where the sea merges with the sky”. His parents also gave him a name, not published here in keeping with his family’s wishes, that means “crystal clear”. Yunupingu means rock.

Yunupingu had just about completed his education when the banyan tree came under threat in the mid 1960s. After the arrival of missionaries in Arnhem Land in the 1920s and 30s and then wartime conflict, Nabalco’s lease to mine bauxite on the Gove Peninsula was the next thing to upend the Yolngu world. Elders sent bark petitions to Canberra exposing secrets they hoped would persuade Balanda (white people) to respect their traditional customs and retreat. When that failed, they turned to the conventional legal system instead.

Yunupingu interpreted for Yolngu elders and helped explain their culture during the famous 1971 Gove land rights case. In so doing, he acquired detailed knowledge of ceremonies and stories belonging to several local Yolngu tribes. Although the Gove case ultimately failed, it became an emotional trigger for the land rights movement, and with that, Yunupingu’s profile grew.

Distinguished by his charisma and combative attitude, he became inaugural chairman of the Northern Land Council after Aboriginal people won land rights in 1976. The next year, the one before he was made Australian of the Year, he told the National Press Club it was “too late … to stop the white man living next to Aboriginals.” He was by then perhaps the closest thing the Indigenous north had ever had to a ruler.

“These are difficult days for all of us, Aboriginal Australians and European Australians, as we learn to live together in a new way with real equality at last,” he told the National Press Club in 1977. “We Aborigines want to share this land with you, and we ask you to share it with us, openly and without fear and secret dealings. We ask you to be as responsible as we have been for 40,000 years in preserving our heritage and environment.”

Yunupingu’s life would come to be defined by the nation’s quest for that balance: he travelled the country as a political potentate, figurehead for Aboriginal causes and counsel to the rich and powerful; upset people with spending habits that seemed to contradict Aboriginal stereotypes and Western mores; and attracted criticism for opposing some progressive causes. Remarking years later on the succession of prime ministers he had met, he said: “I mark them all hard”.

Gumatj clan mythology contains a story about an ancestor who, in the midst of a family dispute, flung a painted log coffin into the Timor Sea. The violent act “lifted people’s eyes … (and) generated the possibility of a different future … bitter division was healed by bold, confident leadership,” Yunupingu once wrote. In teaching Yunupingu to “look up to the future”, his father Mangurrawuy had adopted that ancestor’s spirit. After the old man handed his chosen son his clapsticks on his deathbed in 1979, Yunupingu tried to emulate Mangurrawuy’s resolute style of leadership and his independent mind.

One of Yunupingu’s first forays into controversy came in the early 80s when, fresh from land rights battles over bauxite extraction at Gove, he reversed the NLC’s opposition to uranium mining. Addressing the press club for the second time in 1984, he savaged the left wing of Bob Hawke’s Labor Party for blocking Aboriginal autonomy, much to the bemusement of some journalists in the audience, who apparently expected Indigenous Australians to universally endorse environmental causes.

Addressing the leader incorrectly as “Mr Yurupingu”, a reporter from radio station 2XXX said: “I understand your position that at the moment if uranium is mined it is good for your people from a financial point of view however do you appreciate that there is a wide movement around the world including in Australia which says to the Australian people ‘leave uranium in the ground because it is dangerous for the whole world’? Now, are you prepared to take the position of the short convenient matter for your own people of gaining land rights, gaining control of the mining while the rest of the world says ‘we don’t want Australian uranium to be involved in potential nuclear conflict’?”

Audio of the event held by the National Library of Australia records Yunupingu sounding exasperated as he begins his response with the word “well” and exhales.

“We are talking about Aboriginal people who have made up their mind about mining … the point is they have made the decision and that’s number one,” Yunupingu said.

“They own the land that’s number two. Their decision is so important that should be taken note of and since they have made the decision of mining uranium on their area nothing else matters.

“That’s their decision and whatever people in other countries or throughout are saying that’s their problem not ours. We are not in the position of making decisions for Australia we leave that for the government who is in power.”

The economic benefits of uranium mining should be available to Aboriginal people equally if they were to others elsewhere, and that was for governments to decide but not on a case-by-case basis. Land ownership was power, land management its symbol and decision-making an exercise of that power. The three could not be separated.

“For nearly 200 years, we were forced to do everything white men wanted. We were taken from our mothers, denied proper education and kept in one place. We were made to worship white man’s god, wear his clothes and eat his food. He made us look like him, but he did not treat us as equals,” Yunupingu told the audience. “We will not throw away our blueprint for life and take your laws when even you have to keep changing your laws because they don’t work for your culture … our past is our system of life, then, now and for the future. It cannot be changed, and we cannot tell lies about it.”

That final point, repeated over and over as the years progressed, rankled some observers. If Aboriginal culture were flawless and static, why did Aboriginal people seem susceptible to modernity’s excesses? Did they not need protecting from themselves? Consistent with Yolngu warnings rather than government expectations, social security benefits induced idleness rather than agency. But the royalties that came with land rights poured into a system of tribal patronage outsiders found distastefully reminiscent of medieval feudalism. Yunupingu thought what he did with his money was no one else’s business.

Writing in 1996 for this newspaper, about Yunupingu and his brother the late Yothu Yindi frontman Dr M Yunupingu, Elisabeth Wynhausen noted Yunupingu’s use of a hired crane to lift a new fridge “as big as the Ritz” onto the balcony of his Gove house. She also remarked upon his autocratic approach to Gumatj finances and indulgence in helicopter travel. Complaints (including some from family members) triggered a series of audits whose findings proved hard to disentangle from the distaste institutions in Canberra and Darwin evidently felt for “a well-born Australian Aborigine who doesn’t merely fail to kowtow, but may refuse to be agreeable,” borrowing from Wynhausen again. Relations between Yunupingu and his brother frayed as control of Garma Festival and the Yothu Yindi Foundation passed from those associated with Dr M Yunupingu’s band Yothu Yindi into Yunupingu’s orbit. In the cultural way, Yunupingu always held more power.

In 2003, Yunupingu opposed Northern Territory Labor’s amendments outlawing traditional marriage as a defence against crimes of unlawful sexual relations with underage girls. In 2008, he put forward his own family members to talk about the prostitution of underage girls by mine workers, declaring that “everybody here knows what has been going on and the time has come for us to put an end to this once and for all.”

Four years later, Yunupingu entered an important collaboration on constitutional recognition with two of Australia’s great intellectuals – Marcia Langton and Noel Pearson.

John Howard’s government had just launched the NT Emergency Response (NTER) to the Little Children Are Sacred report in a blaze of publicity in June 2007. Yunupingu at first called it “sickening, rotten and worrying.” He feared losing his land rights. But only weeks later, in a meeting brokered by Pearson, Yunupingu and the then indigenous affairs minister Mal Brough found themselves of similar minds. They negotiated a lease that left Yunupingu “more in charge than I had ever been” of his own country, jointly backed banning drugs and Kava and discussed other harsh measures.

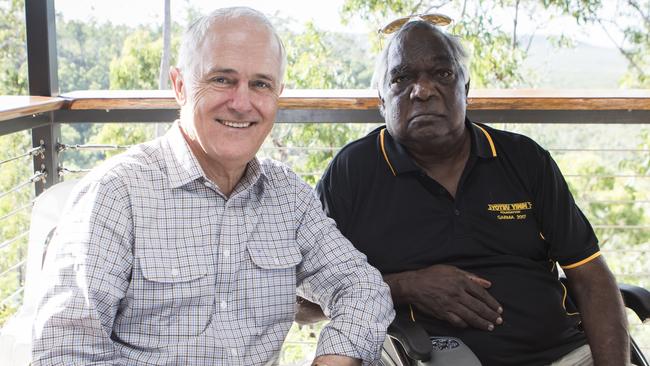

Yunupingu sent Brough back to Howard with a plea for constitutional change. Howard promised an Indigenous recognition referendum if he retained power at the November 2007 election. This was the beginning of a decade of bipartisanship on the issue of constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. It led ultimately to the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart and its call for a voice in the constitution, a step too far for then Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and his successor Scott Morrison.

Yunupingu’s plea was for “serious business”. He viewed Yolngu law as akin to a constitution, not a legal system: it was a doctrine protecting rights that could not be infringed. Mangurrawuy and other elders retained memories of massacres (including that of Wonggu’s father in 1910) and yearned for Australia to enshrine something to stop past deprivations ever being repeated, he told a Melbourne audience. “These stories are very real to every person in Arnhem Land — they are living memories,” he said. “My whole adult life has been a struggle for my rights.”

Successful recognition needed to protect Aboriginal rights (“what is ours and what has been taken from us”), provide recognition “within the nation” that could be broadly endorsed and resolve indigenous disadvantage. Disagreement between those who support the existing constitution that largely eschews rights and others wanting Indigenous rights to be underscored has been at the heart of the Indigenous recognition debate.

The last Garma festival Yunupingu hosted was the most significant in the event’s 23-year history. It is when the newly-elected Anthony Albanese chose to announce the draft words of a constitutional amendment to enshrine an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice. At Yunupingu’s welcome speech the year before, he had warned the then Coalition government to fix the constitution or his people would throw it in the sea.

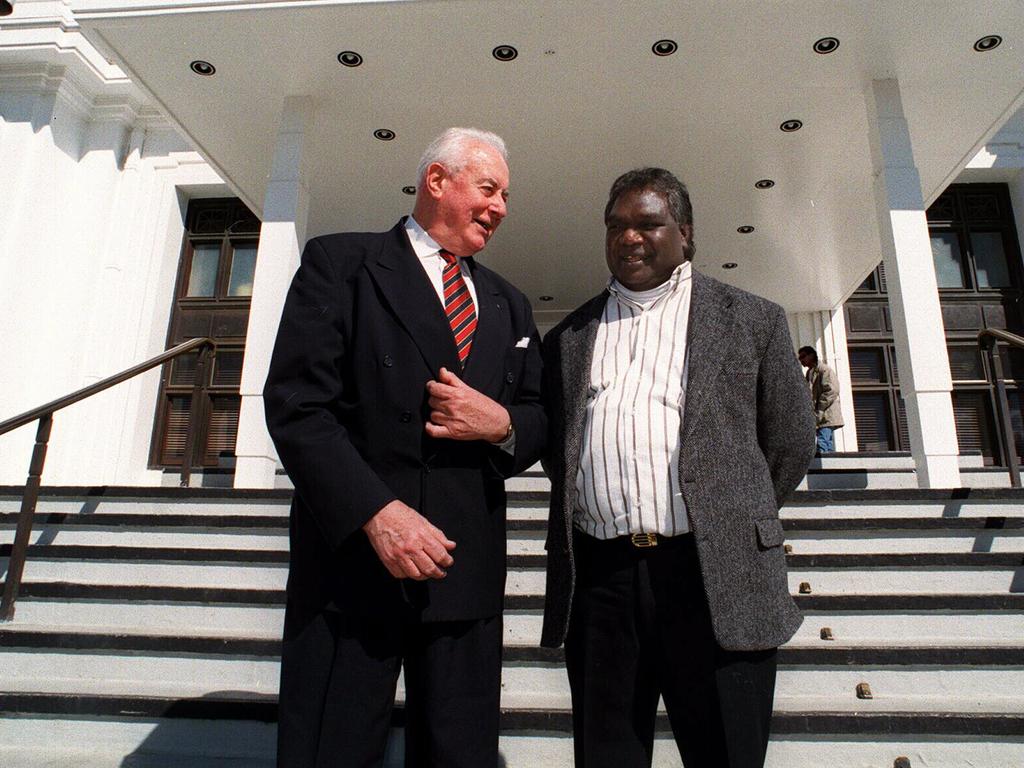

By the time of Albanese’s Garma speech on July 30, 2022, Yunupingu was accustomed to being disappointed by prime ministers. In 1988, he was in his second stint as chair of the Northern Land Council when he helped write, paint and present the Barunga Statement to Bob Hawke at the Barunga Festival, along with Aboriginal leaders from across the Northern Territory. It called for a treaty and Hawke agreed to develop one by 1990. It was Labor policy but it did not happen.

When Albanese finished his historic announcement and took his seat next to Yunupingu, the clan leader was heard asking him: “Are you serious this time?”

Albanese replied: “Yes we are going to do it”

Almost eight months later, as Yunupingu entered the final weeks of his life at his home, Albanese phoned him to tell him the wording of the constitutional amendment for the voice was finalised and he was taking it to parliament. In what those in the room with Yunupingu described as a moving conversation, Albanese paid his respects.

“You were truthful,” Yunupingu told him.

In his final years, Yunupingu threw himself into songlines and ceremonies, attempts to rescue family members from social dysfunction, a series of micro-businesses aimed at training youngsters to confront modernity’s pressures without losing their roots. An article in this newspaper based on one of his last significant interviews portrayed him as “an antique leader in a world few younger people strongly wish to occupy and own”.

Yunupingu described his father as “a hard, relentless man” in whose image he tried to serve his people. “He always had to reserve and balance his power and his strength and his intelligence, for when you were with him, his tongue could be like fire, to burn you alive, to cut you in pieces, and leave you without words, struggling, gasping for life,” he told Nicolas Rothwell. He saw no such successor among his own sons. One more big success came in 2011 with the negotiation of a proper mining agreement for Gove. A friend says that left him “finally at peace” and brought the saga that began with the banyan tree to at least a partial close.

As his health began to fail – ultimately he would have a kidney transplant – and the Gumatj clan became embroiled in lawfare with other tribal groups over royalties, Yunupingu retreated farther.

Shortly before a Yolngu ceremony in late 2015 marking his retreat from frontline duty, Yunupingu judged the Yolngu world safer than when his father passed away but added Australia was still avoiding “the hard questions”. He arrived at the ceremony in his gold Lexus with extravagant flames down the side, wearing his trademark mirrored aviator sunglasses, to be met by painted-up youngsters doffing workwear and chattering on mobile phones.

“The rules of ceremony are very strict,” he told The Australian. “The most important thing for me is my ceremonial teachings, which show me how to live and to lead the proper way. There’s no other way. There are other ideas and laws and teachings, and all that might interrupt me, but I must tell the difference between them and my ceremonial laws, which are the only ones to live by.”

The words that perhaps best captured the enigma of the moment and of Yunupingu’s life had been spoken by the old man and printed in this newspaper a few years earlier. “I limit my private life,” he told the reporter, “to my close family and friends: I tend not to give away myself, who I am, what I’m about; not even to my wives. There’s very little of me that anyone really knows, and it worries me enormously that this core of my self goes unseen. Of course, there’s always a part of you that should be reserved, or you become vulnerable. And that’s why I have never opened up completely, to anyone, about my life. I give so much of myself away, in public things, that I have to hold this core of me back, and have a secret self. And when I talk, sometimes, in my thoughts, I tune myself up, so high I can’t even hear myself speaking: and I wonder, then, who understands me – who could understand?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout