Honours debate: For services to the rich and powerful

Critics say Australia’s leading civilian honours go to the big end of town while unsung, grassroots heroes pick up the crumbs.

It ought to be a time for celebration — of what it is to be Australian, of mateship, of selfless hard yakka and good old Aussie know-how.

Instead, the announcement of the nation’s top awards each Australia Day and Queen’s Birthday is often greeted with as many howls of derision as it is with applause.

Earlier this month, the focus was on potty-mouthed shock jock Mike Carlton, whose Member of the Order of Australia prompted outrage from Liberal MPs, given his history of attacking critics in torrid terms, such as “Jewish bigot”.

Last year, Carlton hit a new low, tweeting his mystification as to why Q&A panellist Jimmy Barnes did not “leap from his seat and strangle” Liberal MP Nicolle Flint.

However, the willingness of the Council for the Order of Australia, which dishes out the awards, to overlook such poor behaviour is hardly an isolated case.

After the last Australia Day Awards it was the AM for Bettina Arndt that sparked outrage. The gong came not long after the author and commentator was forced to apologise for suggesting Nicolaas Bester, a Tasmanian teacher who repeatedly abused a 15-year-old girl, had been “persecuted” by feminists. Some schoolgirls, Arndt had further claimed, were “sexually provocative” towards male teachers.

Other past gong recipients have somehow included an alleged rapist, Liang Joo Leow. The Sydney dermatologist was awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia last Australia Day, despite having been charged in 2018 with raping a Victorian doctor by allegedly removing his condom without consent.

Leow, who denies the allegations, is awaiting trial on one charge of rape and one charge of procuring sexual penetration by fraud.

Last year, an AM also went to far-right Fraser Anning Party candidate Adrian Cheok, who once described Labor senator Penny Wong as a “half man” and had been accused of making Islamophobic social media posts.

One of these captioned a picture of a burqa-clad woman alongside a polling booth with the words: “Who or what is voting for what or whom?”

A range of people, from those who’ve been involved in the award process to those who study its outcomes, believe too many awards are being granted, too often to those who don’t deserve them, and that the entire system is “arse-about”.

The most prestigious awards — the Companion of the Order of Australia and the Officer of the Order of Australia — tend to go to big names; some would say the big end of town: ex-politicians, judges, high-flyer businessmen, media types, academics and esteemed medicos.

While the awards are meant to be for achievements of the highest order, it often seems these people are getting gongs primarily for doing their jobs, albeit very well, perhaps with a bit of charity support on the side.

Our most remarkable community heroes — those doing selfless voluntary work or going “above and beyond” in helping others, year-on-year — tend to receive the lowest award: the Medal of the Order of Australia.

A lucky few of these grassroots quiet achievers might receive the gong one level up, the Member of the Order of Australia.

While some argue this is just the way the awards are structured, and awards of all levels are valuable, there is a push for change.

“I don’t see why someone who has fostered 105 children for 28 years should receive a community service award and a politician walks away with what is considered a more national award,” says Kerri-Anne Kennerley. “That is arse-about. I think probably it is time for a review.”

The veteran TV presenter has inside knowledge, having unsuccessfully mounted such arguments while serving for several years on the Council for the Order of Australia.

“I believe the system does need a look at. I think there are too many awards given and too many famous people get them just for being famous,” she tells The Australian. “It’s not the Logies.”

In the top two awards — the AC and AO — in the most recent Queen’s Birthday honours civil list, only four of 53 recipients gained their gong first and foremost for service to the community, rather than to a profession or area of work.

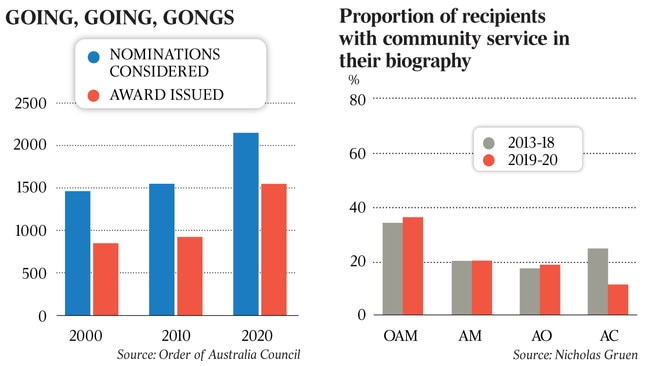

Economist Nicholas Gruen, visiting professor at University of Technology Sydney and Kings College, London, crunches the numbers in terms of who gets what each year. He agrees the top awards are weighted to high-status Australians.

His analysis shows that from 2013-18, less than 30 per cent of all AC recipients had done any community service, dropping to little more than 10 per cent in 2019-20, not including this month’s Queen’s Birthday honours. “If you look at the most senior ACs … I do sit and wonder why we should say that they are worth a better award than someone who has worked with their local community for 40 years and helped orphans find employment,” Gruen says.

He believes one way of tackling this bias would be a citizens’ council, to inject the values of “ordinary people” into the selection process.

“You ask 25 people from the Australian community who might be chosen at random, like we do with a jury, and you ask them to deliberate on the kinds of values they want to reward,” he says.

Very few recipients will publicly criticise the process. A notable exception is former chief of the defence force, Chris Barrie, who not only served on the council for four years, but received an AM, upgraded to an AO and then an AC.

“I think the criticism that a lot of people get the higher awards because of what they do in their professions has quite a lot of substance to it,” Barrie tells The Australian.

He says medical, legal and even military organisations see it as “very important” to secure awards and upgrades for their members and work “pretty assiduously” at pushing their person’s case.

Barrie strongly backs a system of national awards and believes a review could consider whether more of the higher honours should go to grassroots community achievers.

“The bulk of them (top awards recipients) are at the top of a profession or calling and most of the community people are down in the AMs and OAMs,” he says. “This is egalitarian Australia but what we’re doing in the current system is sort of preserving a hangover of the British imperial system.”

The 19-member Council of the Order of Australia argues it is independent and fair. Anyone can nominate anyone. However, the council does appear to be largely a creature of politicians and bureaucrats. It includes 11 representatives of state and federal governments, as well as a chair.

Even the six or seven “community representatives”, sound folk though they undoubtedly may be, are appointed by the governor-general on the prime minister’s say-so.

Chaired by former Northern Territory chief minister Shane Stone, AC, the council rejects much of the criticism, including the gripe that too few community heroes are receiving top gongs.

“The level of award does not denigrate the value of that service or the contribution that the recipient has made,” a council spokesman said.

Even so, the language of the awards suggests a clear hierarchy. AC is “for eminent achievement and merit of the highest degree in service to Australia or to humanity at large”; AO is for “distinguished service of a high degree or to humanity at large”; AM is for “service in a particular locality or field of activity or to a particular group”, and finally, OAM is awarded for service “worthy of particular recognition”.

Of course, those community heroes who are awarded OAMs or, more rarely, AMs never complain they didn’t get an AO or an AC. Like most Australians, many do not understand the distinction.

“I thought OAMs were higher because they have more letters,” says Sarah Brown, a Northern Territory remote area nurse awarded an AM in the recent Queen’s Birthday honours.

Stone’s council also denies ACs and AOs tend to be given to people simply for doing their jobs. “The council generally looks for service of nominees over and above their paid employment — whether it be through direct volunteering, service more broadly to the growth of professional organisations, boards, research or educational roles, philanthropy or other endeavour,” a council spokesman says.

Those involved in the vetting process insist due diligence, including trawling recent social media posts, does occur. However, they argue any dodgy baggage must be weighed against the person’s achievements.

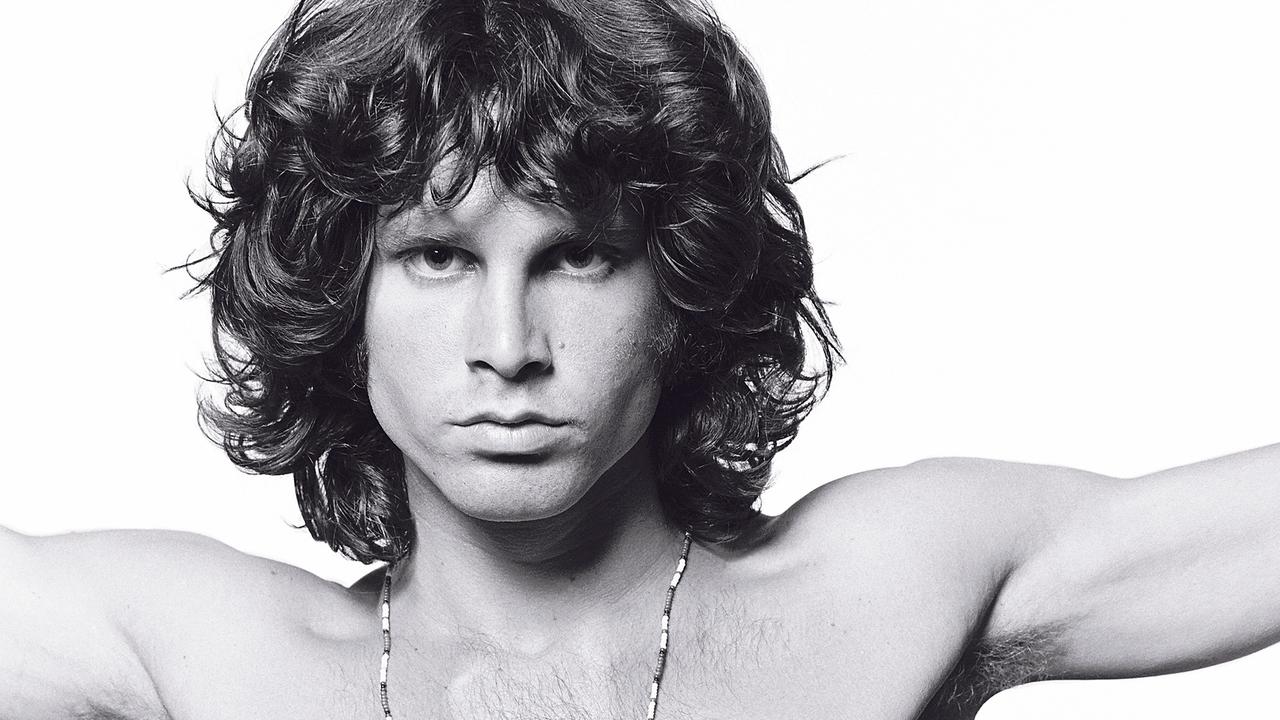

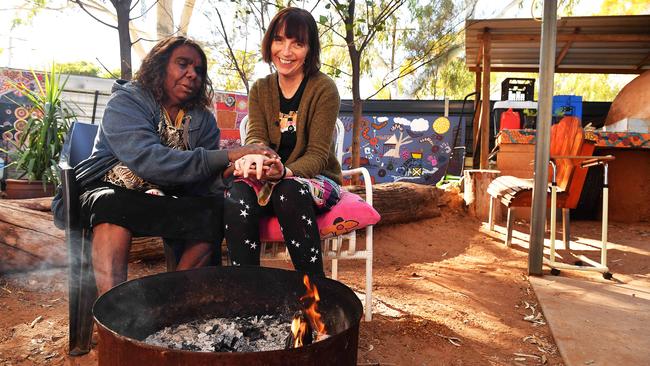

Brown, the Northern Territory remote area nurse awarded an AM, worked tirelessly for 17 years to get dialysis machines and nurses to 18 remote communities. She is an example of the grassroots battler who Kennerley, Gruen and others would like to see given the nation’s top award.

For her part, Brown is simply thrilled at any recognition and the profile and support it provides for her Purple House organisation, based in Alice Springs.

She urges Australians to force change through the nomination process. “Nominate people — if you make a bit of effort, you might see a change, because they’ll be flooded by grassroots people,” she says.

Nominations are on the rise, but so too is the proportion of nominees granted an award.

Figures obtained by The Australian show an almost doubling of awards since 2000, while the number of nominations has failed to keep pace with the largesse.

Since 2000, the number of nominations has risen from 1462 to 2149 but the number of awards issued has soared, from 847 in 2000 to 1547 in 2020.

The percentage of nominations given the green light has increased from 58 per cent in 2000 to 72 per cent this year.

Governor-General David Hurley, who announces the awards, has taken a keen interest in fostering their status. He welcomes debate and appears open to an “evolution” of the awards to best reflect Australia’s changing society.

“I am determined, across my term in office, to ensure that the Order of Australia is — and is perceived to be by the Australian public — the highest form of recognition of the efforts and achievements of Australians,” General Hurley tells The Australian.

“At the end of the day the Order of Australia belongs to and represents all Australians. They must have confidence in it. It must continue to evolve — as our society does — and reflect and recognise the best of Australia.”

● Liang Joo Leow was acquitted of the rape charge in October 2023 at the County Court of Victoria.