‘Holy grail’ fish discovery comes with one big catch

The discovery of a rare, untapped, abundant and delicious food source off Australia’s southern coast is quickly shaping as an unsavoury battle.

It sounds like the holy grail of food sources. An untapped, abundant, delicious source of protein with amazing health benefits, low carbon impact and no need for land clearing, chemicals or fresh water.

But plans to open up a new Australian fishery – to exploit an untapped sardine resource in southeastern waters – is shaping as the biggest offshore environmental stoush since the super-trawler more than a decade ago.

New fisheries are a rarity, so there is palpable excitement at the recent “discovery” of 210,000 tonnes of sardines across a 150,000sq km area south of Victoria and off southern NSW and Tasmania’s north and east coasts.

Led by scientists from the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, a major study of sardine eggs released late last year proved what some had long suspected.

“The spawning biomass of this stock is sufficiently large to support a substantial commercial fishery,” concluded the study, published by the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation. This was particularly good news for the Tasmanian Liberal government, which part-funded the research.

“A significant portion of this stock occurs in waters under the jurisdiction of the Tasmanian government,” the scientists noted, with the highest densities in Bass Strait and off western Victoria.

“Therefore, this study demonstrates the potential to establish a large Tasmanian sardine fishery.”

The state government is moving with uncharacteristic speed, announcing guidelines to develop the new fishery and promising “community information forums” in coming weeks.

“This can be huge for Tasmania if done properly,” says experienced Tasmanian commercial fisher and businessman Stuart Richey, who has long lobbied for the fishery.

Industry and Resources Minister Eric Abetz is seeking to head-off a revival of the super-trawler campaign that resulted in factory ships being banned by the Gillard government in 2012.

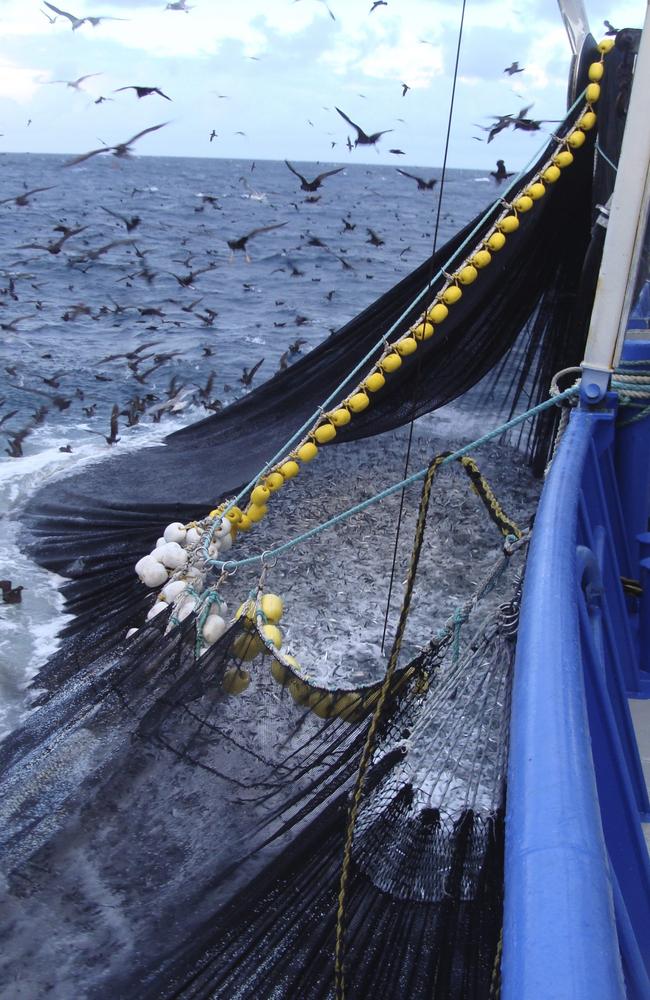

Abetz is promising the fishery will not use trawlers, but rather purse seine methods to target sardines schooling near the surface.

Purse seine nets have an open top and bottom, the top floating on the surface and the bottom weighed down. Once a school of fish is encircled, the net is drawn tight like a stringed purse to trap the fish.

Abetz argues it is more environmentally friendly than trawling, with no impact on the sea floor and less risk of by-catch (catching the wrong species, including dolphins, sharks, seals and seabirds).

So what’s the problem?

Much concern focuses on the vital role small pelagic (open ocean) fish, such as sardines, play in the ecosystem, as a cornerstone food for predators ranging from larger fish, such as tuna, to seabirds, seals and dolphins.

“The real problem is that sardines are a forage fish, which most if not all predators in some way rely upon,” says Alistair Allan, Bob Brown Foundation marine campaigner and Greens candidate for Lyons.

“We shouldn’t be opening up an industrial fishery that attacks forage fish, highlighted globally as linchpins of the ecosystem.”

The Fisheries Research and Development Corporation report relied on by government, however, argues this is less of a concern in southeastern Australian waters than elsewhere in the world.

“Dietary analyses and ecological modelling have shown that, unlike many other marine ecosystems worldwide, predatory species in the marine ecosystems off southern and southeastern Australia are not highly dependent on one or more species of small and medium-sized pelagic (forage) fishes,” the report notes. “Harvesting these species, including sardine, both singly and in combination, has only minor impacts on other parts of the ecosystem.”

Even so, the FRDC report acknowledges much is still unknown about the sardine population, and caution is needed. “Because this resource has only been discovered recently, and patterns of inter-annual variability in stock abundance and recruitment are not well understood, we recommend a precautionary approach,” the scientists urge.

Even fishermen who support the new fishery, such as Richey, want a slow, small start to allay public concerns. The FRDC report recommends limiting the total catch to under 15 per cent of the estimated sardine resource – about half the rate deemed sustainable.

Australia has four sardine stocks: west and south of WA; south of SA; the recently “discovered” southeast area; and northern NSW to southern Queensland.

Total catches are generally low, although the already established SA sardine fishery, based in Port Lincoln, is allowed to take up to 25 per cent of the resource – a maximum 50,000 tonnes – a year.

Richey urges the government to be even more cautious in setting catch limits for the new Tasmanian fishery than the FRDC recommendation.

“Even though there’s terrific science out there now that says there’s a hell of a lot (of sardines), we still have to get the public on board,” he argues.

“After the debacle of the super-trawler, people want some confidence. So let’s start this low and gradually build it up.”

The FRDC’s 15 per cent would equate to more than 30,000 tonnes, but Richey, who has purchased a seafood cold store in the Huon Valley with sardines in mind, suggests starting at about 7000 tonnes. Such concessions are clearly aimed at allaying concerns held by recreational fishers, a powerful lobby group, particularly in Tasmania.

The island state naturally has high rates of boat ownership. Catching fish – including species that eat sardines, such as tuna and kingfish – is a sacred pursuit for many. A good chunk of these tinnie warriors double as marginal seat voters, explaining why the Gillard government shut the ports to super-trawlers in 2012, despite similar science about low impacts.

The Tasmanian Association for Recreational Fishing warns its members are “concerned and nervous”. So much so the group has taken the extraordinary step of forming a “reference group”. While not yet a council of war, creation of the group should be ringing alarm bells in Abetz’s office.

TARFish chief executive Jane Gallichan explains the group will “guide how our organisation participates and responds as more information becomes available”.

“There is some concern and nervousness among recreational fishers, largely driven by a lack of detailed information or answers to their questions,” Gallichan explains. “It will be incredibly important that any new fishery is trialled with the highest level of precaution, and recreational fishers are assured that their fishing won’t be impacted.”

Perhaps the biggest potential PR problem for the new fishery is everyone’s favourite marine mammal. Dolphins, like fishing boats, go where there are fish, bringing them into contact with nets, which can trap and drown them.

Purse seining, rather than trawling, provides more scope for fishers to release trapped dolphins, but mortalities have occurred in the SA sardine fishery.

Data on reported dolphin deaths in SA’s sardine fishery shows a peak of 24 mortalities in 2005. Since then, mortalities have ranged from nil to 16 a year. In 2023, there were two reported dolphin deaths. In 2022, six deaths.

In 2024, the issue of dolphin deaths frustrated attempts by the SA sardine fishery to retain top-flight sustainability certification.

In May 2024, the fishery withdrew from Marine Stewardship Council certification, the global badge offering fish-loving consumers a guilt-free feed. Certification assessment documents show withdrawal came after the fishery failed to provide MSC with sufficient confidence in its strategy to manage impacts on dolphins.

Certifiers were troubled by a discrepancy between mortality rates when independent observers were on board boats and self-reported rates when no observers were present.

“It is unclear if the information collected is adequate to measure trends and support a strategy to manage impacts on … dolphins,” auditors found.

Those involved in the $31m SA fishery argue all fishing involves the risk of dolphin mortalities, and they say there were no mortalities in 2024. Further, they say they are trialling dolphin deterrence devices that promise to reduce interactions even further.

There are also deep suspicions about where the new Tasmanian fishery’s sardines will end up.

Sardines are one of the best sources of healthy omega-3 oils, and much loved across Europe.

However, Australians are only beginning to warm to their rich, uber-fishy flavour.

Traditionally, Aussies prefer white-flesh fish, such as whiting and flathead. This explains why about 95 per cent of the SA sardines are fed to wild-caught, ranched tuna, to fatten them for market. It has led to concerns in Tasmania that almost all the sardines from the new fishery will end up in feed for local salmon farms.

Salmon Tasmania insists it is not driving the development of the sardine industry, but agrees it could eventually come to replace imported ingredients for salmon feed.

With salmon farming a hot-button issue, would-be sardine fishers are worried the connection is yet another barrier to public support.

“We want to get as much as possible into human consumption, then look after the recreational bait market and any waste left over could of course go into salmon feed,” Richey says. “This thought that it might go into salmon feed risks hijacking a sensible debate.”

It is certainly fuelling opposition from the likes of the BBF.

“If the commercial viability of the new sardine fishery rests on feeding salmon farms – which pollute the ecosystem – it’s an environmental crime in the making,” Allan argues.

Abetz is not committing to any specific catch limits or dolphin-avoidance strategies but promises the new fishery will be “precautionary” and “best practice”.

“The government’s vision for the fishery is a jobs-rich and profitable, socially responsible, ecologically sustainable and commercial fishery that delivers tangible economic and social benefits to the Tasmanian community,” Abetz says.

He insists “the highest bidder” will determine where the fish end up but foresees “a source of protein that can be distributed nationally, eaten in our restaurants, and used for pharmaceutical purposes”.

How the plans proceed will determine whether Australia’s newest fishery really is a holy grail, or instead a poisoned chalice.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout