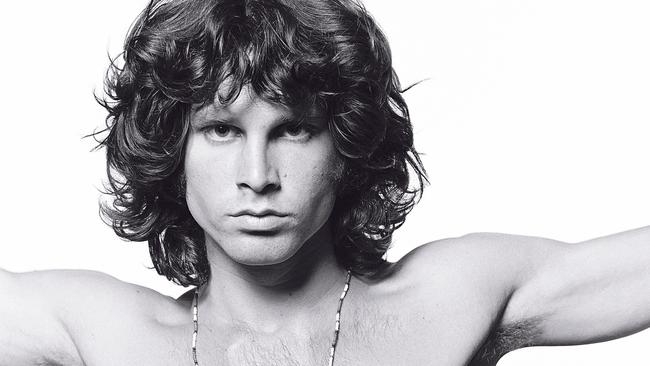

Jim Morrison’s ‘lost’ songs found in timber home in Tasmania

People are strange, The Doors told us, but no stranger than the tale of Jim Morrison’s ‘lost’ songs, believed to have turned up in a cluttered timber home on a remote hill in the Tasmanian bush.

Where else would lost songs of Jim Morrison turn up than in a cluttered timber home on the side of a remote hill in the Tasmanian bush?

Retired lawyer Roger Baker, acting as executor of the will of top American music producer John Haeny, has stumbled across what he believes are unreleased recordings of Morrison’s music, as well as an unreleased album from jazz legend Duke Ellington.

The reel-to-reel recordings form part of a bountiful estate left behind by Haeny, pioneering producer, mixing engineer and sound designer to a host of jazz and rock greats, including Morrison and The Doors, John Coltrane, Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Cher and Joni Mitchell.

Mr Baker, whose late wife Rosie Wilson knew Haeny well and was his original executor, is selling his sound and mixing equipment, but is yet to clarify rights or ownership of the “lost” recordings.

“We believe that there is one unreleased Jim Morrison tape – the original – and also we believe an unreleased album of Duke Ellington,” he said. “There are names of tracks that have not been released. It’s always possible that they were given different names on release, but on good evidence it’s believed that these are unreleased.”

Some of the Morrison tracks are marked “never released” or “unreleased”, including “whiskey and wild woman”.

There was more research and legal work needed to determine their ownership and who had the right to release them, preventing him from doing so. “The IP (intellectual property) relating to the music and words is going to be held by the composer, but we don’t know whether there has been any assignment of the IP from one person to another,” he said.

Despite the potentially global interest new Morrison or Ellington tracks would generate, some parties had not responded to requests for assistance. However, the Duke Ellington Foundation could be sent the tracks attributed to him. Mr Baker focus to date had been on disposing of the Haeny estate’s large items – mixing decks, sound equipment, turntables and 38 speakers – that are about to be auctioned online.

Determining the fate of the tapes – featuring at least six potentially unreleased Morrison tracks – was “the next step”. He had not yet attempted to play the tapes, but they appeared to be music, as opposed to spoken word – significant, as Haeny worked on Morrison’s poetry album, An American Prayer.

There had been discussions with people competent in the use of the equipment needed to play the old tapes, but also concern to avoid damaging them. For this reason, it was likely the tapes would be taken to an expert at the University of Tasmania to be played. “They’re all reel-to-reel but of different widths, which has some relevancy to the type of machine needed to play them,” he said. “That is something we will do, most likely at the university because they have suitable equipment.”

He was confident they would eventually see the light of day. “One day they will emerge – they can’t live in my secure lockup facility for ever,” Mr Baker said.

There is particular sensitivity around the Morrison recordings because of a history of litigation involving the surviving members of The Doors.

Most recently, Doors drummer John Densmore sued former bandmates Ray Manzarek and Robby Krieger, demanding they stop touring as The Doors of the Twenty-First Century and seeking to prevent the use of Break on Through (To the Other Side) in Cadillac commercials.

Haeny recorded Morrison’s poetry after he left The Doors. One recording session – on Morrison’s 27th and last birthday on December 8, 1970 – turned into a drunken party, with tapes still running. Haeny bought Morrison a bottle of Bushmills Irish whiskey as a birthday present. “It was my plan to document Jim reading his poetry on his journey from cold sober to that locked room where his drunken Irish poet lurked,” Haeny wrote decades later. “Although we never discussed it, I had an overwhelming feeling that Jim knew exactly what I was up to and was happy to go along with me.”

Seven months later, on July 3, 1971, Morrison died of heart failure in Paris. Haeny had planned to join him there to finish the poetry project. “Sadly, I never made it to Paris and Jim never came home,” he recalled years later. But Haeny realised Morrison’s vision seven years later, working with Doors members to release a posthumous album of the poetry, set to music (An American Prayer).

So how did Haeny and his tapes end up in a timber home on a bush block, up a dirt road near Glen Huon, in the Huon Valley, south of Hobart?

Haeny moved from the US to Sydney in 1992, becoming head of sound at the Australian Film TV and Radio School.

Described as assertively gay, he is said to have then followed a love interest to Tasmania. While the relationship apparently did not work out, Haeny found love in another form: that timber home “on 10 beautiful rolling, isolated acres, at an altitude of 400m”.

Here he used several rooms as a “Sunny Hills Recording Studio” and continued working for many years, including with well-known Australian bands such as Mental as Anything. He was wheelchair-bound for the last five years of his life and died after an illness on September 19, 2023, aged 82.

As well as unlocking the secret of those “lost” tapes, Mr Baker will also in coming months comply with Haeny’s dying wish: “One of my duties is to mix his ashes with those of his late mother and various pet cats and dogs, and scatter them in international waters.”

As well as his extensive work with recording artists over 50 years, Haeny worked on many film and TV scores, including Twin Peaks, Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves and Beauty and the Beast.

While the tapes are not for sale, Hobart’s Gowans Auctions is expecting interest from far and wide in its auction of Haeny’s impressive studio equipment.

“It’s exciting for us to handle a collection from someone such as John who was internationally acclaimed – it’s not something we handle regularly,” said auctioneer Tim Burt. “We’ve already had a lot of interest.”

The auction – not including the tapes – will be from February 12 to 18, at: www.gowansauctions.com.au

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout